23 The Idaho Higher Education Faculty Usage and Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Survey 2025

Report by Dr. Jason Blomquist, Boise State University; Dr. Sarah Llewellyn, Boise State University; and Dr. Liza Long, Idaho State Board of Education

Dr. Blomquist and Dr. Long thank the Idaho State Board of Education for our AI Fellowship Funding that enabled us to work on this research.

1. Executive Summary

Overview

The Idaho Higher Education Faculty Usage and Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Survey (Spring 2025) provides the first comprehensive statewide assessment of faculty and instructional staff engagement with artificial intelligence (AI) across Idaho’s eight public institutions (n = 478, 10.8% response rate). Results reveal a faculty body that is simultaneously innovative, cautious, and eager for institutional direction. Many faculty are already incorporating AI into teaching and research, but widespread uncertainty, uneven confidence, hesitancy, and gaps in professional development signal the need for coordinated statewide leadership.

AI Usage and Confidence

Nearly half (46%) of respondents report using AI weekly or more, demonstrating that AI has quickly become a part of instructional practice. However, only 30% describe themselves as highly confident users, suggesting that adoption has outpaced training and policy development. Respondents are using AI primarily for brainstorming, explaining concepts, and summarizing material; applications that enhance efficiency and creativity rather than replace instructional expertise.

Professional Development and Institutional Support

Respondents’ enthusiasm is tempered by a strong call for more training and clearer guidance. Sixty-four percent of respondents report that their institutions offer AI-related professional development, yet nearly one in four are unaware of these opportunities. Respondents emphasized the need for recurring, hands-on, and discipline-specific training that includes ethical and pedagogical dimensions. Respondents also requested clearer institutional policies and administrative support to guide responsible AI use and safeguard academic integrity.

Teaching Practices and Student Use

AI is already shaping the classroom experience. Seventy-eight percent of respondents address AI use in their courses, and two-thirds permit students to use AI tools for certain tasks such as brainstorming, research, and summarization. Respondents are not avoiding AI, they are actively piloting policies at the course level. However, these approaches vary widely across institutions and disciplines, resulting in inconsistent expectations for students and instructors alike.

Concerns and Ethical Considerations

Respondents expressed concerns about accuracy, bias, academic dishonesty, and the potential for AI to diminish creativity and critical thinking. Many reported feeling pressure to adapt without sufficient time, training, or institutional backing. These concerns underscore the importance of developing statewide frameworks that support responsible, human-centered integration of AI while protecting the values of higher education.

Institutional Readiness

The survey highlights disparities between large, research-intensive universities and smaller, rural colleges in access to AI tools and training. Without statewide coordination, these inequities may deepen, leading to uneven opportunities for faculty and students. Addressing this gap requires investment in shared infrastructure, professional development, and access to technology.

Path Forward

Idaho stands at a strategic inflection point. Respondent’s engagement with AI is strong, but institutional responses to AI have not yet matured to support sustainable and ethical use. The Idaho State Board of Education is uniquely positioned to lead a coordinated response.

Key actions include:

- Investing in scalable, discipline-specific professional development

- Establishing consistent frameworks for ethical AI use

- Expanding access to AI tools and infrastructure

- Creating a statewide AI in Higher Education Task Force to guide implementation and monitor progress

With proactive leadership, Idaho can move from fragmented experimentation to strategic coordination, positioning its higher education system as a national model for responsible and human-centered AI integration.

2. Introduction

The Spring 2025 Idaho Higher Education Faculty Usage and Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Survey provides the first comprehensive statewide assessment of how faculty and instructional staff across Idaho’s eight public institutions are engaging with artificial intelligence (AI). Results reveal a faculty body that is simultaneously experimenting, cautious, and eager for support. Nearly half (46%) of respondents report using AI at least weekly in their work, though fewer than one in three (30%) describe themselves as highly confident users. While 64% say their institutions provide AI-related professional development, many remain unaware of or unable to access these opportunities.

Generative AI has emerged as a transformative force in higher education, reshaping teaching, learning, and research practices at a pace rarely seen with other technologies. Faculty nationally report experimenting with AI to save time, spark creativity, and enhance pedagogy, but they also express profound concerns about student learning, integrity, and ethics. Idaho’s higher education system faces these same pressures while also navigating the unique challenges of scale, geography, and resources. Large research institutions may be able to experiment more freely, but community colleges and rural campuses risk falling behind without state-level coordination.

The Idaho Higher Education Faculty Usage and Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Survey was designed to address this gap by providing actionable data to the Idaho State Board of Education. By capturing respondents’ perspectives across all eight public institutions, this survey offers insights into adoption rates, confidence levels, training needs, teaching practices, concerns, and perceived benefits. The results are intended to guide policymakers in shaping effective strategies for AI integration that balance innovation with responsibility.

3. Methodology

To identify a target population for the survey, the research team utilized the National Center for Education Statistics’ Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. As of Spring 2025, the data set reported a total of 4431 “Instructional Staff” (generally referred to as “respondents” in this report) across Idaho’s eight institutions. The research plan, survey, participant recruitment, and data management plan were approved by the Boise State University Institutional Review Board.

The survey instrument combined Likert-scale questions, multiple-choice and multi-select options, open-response items, and demographics; collecting anonymous responses in Qualtrics. It was distributed to respondents across Idaho’s eight public institutions through Idaho State Board of Education AI communications, institutional provosts’ offices, and peer to peer communication in Spring 2025. The sample included respondents across a range of disciplines, academic ranks, years of service, and instructional modalities (in-person, online, and hybrid). While the response rate varied by institution, broad representation was achieved with 478 complete and/or partial responses collected for a response rate of 10.8%.

This report represents initial descriptive statistics and thematic analysis, including both human and AI-assisted analysis, of the survey data. To ensure participant anonymity due to the sample size disparities from certain institutions, aggregated results will be shared.

4. Findings

4.1 AI Usage & Confidence

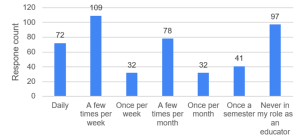

Adoption of AI among respondents is substantial but uneven. Nearly half (46%) report using AI weekly or more, a signal that the technology is already embedded in many professional routines. Yet only about 30% rate themselves as highly confident (4 or 5 on a 5-point Likert scale), suggesting that respondents are using AI experimentally or tentatively rather than with mastery. When asked whether AI was helpful in their educator roles, 43% of respondents reported AI to be “helpful” or “extremely helpful”, while 14% rated helpfulness as “not helpful at all” or zero.

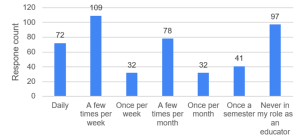

Respondents’ applications of AI are varied. The most common uses include brainstorming course content (46%), helping explain concepts in different ways (41%), summarizing/clarifying concepts (33%), and composing or revising written work (31%). The least reported uses included using AI for grading (8%) and discussion board analysis (8%). These uses point to AI’s role as an instructional assistant rather than as a replacement for faculty judgment or creativity.

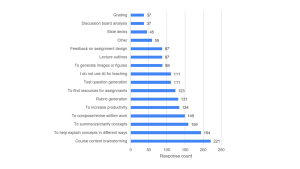

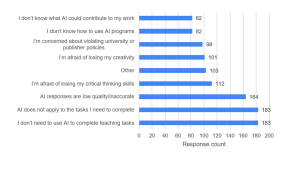

For respondents who reported not using AI regularly, top reasons included a lack of perceived need (38%), a lack of applicability to their work (38%), and concerns over the quality and accuracy of AI responses (34%). When asked to identify the single most important reason for not using AI, the top response was “I don’t need to use AI to complete my teaching tasks” (18%), tied with “AI does not apply to the tasks I need to complete” (18%). The respondents also cited fears that AI use could undermine critical thinking, concerns about privacy, and insufficient guidance on ethical application. These barriers indicate that respondents’ decisions not to use AI often stem from structural gaps in support and policy clarity rather than outright resistance.

4.2 Professional Development & Training

Professional development opportunities exist but are not universal. 64% of respondents report that their institutions provide AI-related training or workshops. However, 23% are uncertain whether such opportunities exist, suggesting communication gaps. Among those aware of opportunities, 60% report having attended at least one session, with 19% indicating they were interested in training but unable to attend. These results indicate a strong interest in continued AI training.

Respondents identified specific training needs, including the desire for trainings on using AI for grading (ethics, AI platforms, FERPA), using AI for administrative tasks including emails and program review, providing real-time feedback to students, research support (grant writing, data analysis), and training scenarios/case studies for use in class.

The desire for training was so strong that over 100 respondents readdressed the issue in the open-ended questions. Training needs varied from basic literacy (hallucinations, prompting, what tools perform what tasks) to the need for systematic planning of training programs (as opposed to multiple “one-off” training) to build AI fluency, including hands-on opportunities. Multiple respondents also addressed the need to understand best practices in AI use in education relating to teaching and learning, faculty use, and supporting faculty who teach online. Concerns were noted about the dynamic nature of AI developments and need for frequent updates when major changes arise. Respondents also wanted discipline-specific training so that they are able to prepare students for the type(s) of AI students may encounter in the workplace.

Administrative support was the next most common need identified by respondents. Over 20 respondents wanted clear guidance on use, specifically requesting policies, parameters, and/or standards of use at the university level. Compliance with AI ethics and FERPA/HIPAA guidelines and support for misconduct were mentioned by respondents, with support for AI detection software, preventing use altogether, and supporting faculty in cases of student AI misconduct provided as examples. Many respondents wanted financial support to purchase AI tools. Those tools may be discipline-specific to match industry use, or paid versions of broader AI tools to increase their capacity in use.

The most common support respondents identified was the need for time to learn, practice, and apply AI technologies. Financial support for attending training or updating courses and workload buy-out were the most frequently presented suggestions.

Some respondents expressed their personal refusal to use AI in their teaching practices, citing dependency on AI tools (“lazy”) and a focus on efficiency over skill as reasons to avoid AI use. Others voiced concerns over AI tools’ ability to perform sufficiently in the tasks assigned and noted they were hired for their position based on their expertise, which cannot be replaced by AI.

This response sums up many of the concerns: “Users without experience overly trust the output and haven’t develop[ed] the skills or expertise to evaluate the output. AI is inherently middle of the road – it lacks life or voice, which itself reinforces existing power structures/ideologies in society. It’s destructive to the environment. It centralizes huge amounts of personal data in the hands of a small group of people – which always opens the door to weaponizing data. Authors are accountable to what they write – AI is not. Training data is largely stolen from others without attribution or compensation.”

4.3 Teaching Practices Around AI

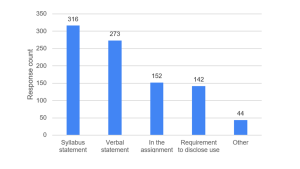

AI is already shaping classroom practice in Idaho. As of Spring 2025, 78% of respondents address the use of AI in their classes, often through syllabus statements (66%) or verbal statements (57%).

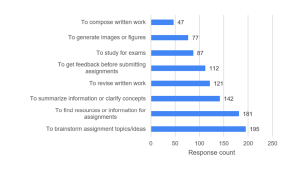

In total, 67% of respondents permit students to use AI in class, though the approach appears to be nuanced, with respondents approving use for certain tasks and restricting use for other tasks. Teaching modality showed modest variation, with 62% of in-person instructors allowing AI use compared to 70% of online instructors and 69% of those who teach both in person and online. Survey respondents who answered “yes” to allowing AI use were asked to select use cases they support. Top choices included brainstorming (66%), finding resources or information (61%), and summarizing or clarifying concepts (48%). Of note, the lowest rated choice was to compose written work (16%). Respondents are not ignoring AI; rather, they are attempting to guide students in responsible use.

4.5 Perceptions of Concerns & Benefits

The survey asked two open-ended questions: first, exploring respondents’ concerns about AI, and second, discussing the benefits (if any) of AI. Results were analyzed independently by a human researcher and by a researcher using Claude.ai as a data analysis tool. The discussion below notes major themes that emerged in both human and AI analysis.

4.5.1 Concerns

In both the human and AI-assisted analysis, respondents’ concerns span several domains. Academic integrity remained paramount: many worried that AI could facilitate plagiarism or erode honest scholarship. Ethical concerns included bias in AI outputs, unequal access, and potential misuse of student data. Respondents also feared that AI could compromise the development of critical thinking and writing skills.

Over 300 respondents responded to the question about concerns with AI use. Three main themes emerged for both the human and AI-assisted analysis. The first concern centered around AI itself. Most commonly mentioned were inaccuracies in output and ethical concerns, especially related to intellectual property and bias. Additionally, concerns were raised around known consequences like the impact on the environment and around the unintended and yet unknown consequences. There was frequent likening of AI to calculators or spell checkers, with some noting the loss of skill related to the ease of the technology while others describe the adaptation that has occurred with those technologies.

The second main theme was around the faculty role. Feeling overwhelmed was the most common. This was represented by fear for their jobs, expectations to be more productive by using AI, and not enough time to learn about AI, its uses, or keep up with the frequent changes. Respondents also relayed existential questions about teaching and learning exemplified by the statement, “If students use AI to complete their coursework while instructors use AI to grade and provide feedback, what is the purpose of the learning process? At what point does it become futile?”. Another concern was around inconsistencies. Respondents cited lack of policies, different uses within departments, faculty members using AI but not allowing students to, and overall confusion around acceptability of use. Another concern was on the challenge in detecting use. Respondents described the challenge between not trusting AI detectors to correctly flag students’ AI use and the fear of wrongly accusing a student.

The final and most prominent theme for both the human and AI-assisted researchers on the impact of AI use on students. The impairment of student learning when using AI was the most common concern. Respondents mentioned students can suffer from skill decay, dependence on the technology, missing out on fundamental skill development, inability to independently explain the why and the process of a skill or assignment and loss of confidence in their own ability in comparison to the AI output. One respondent noted the impact on particular students who use AI stating, “especially vulnerable are those who already struggle and need the most practice, while the good students are more likely to use AI to boost their learning.”

Critical thinking was the next most common concern for students. Many respondents noted the purpose of higher education is to support the development of critical thinking, but if students use AI to complete the assignment, they are missing out on that development. Other respondents mentioned the loss of problem solving and decision making skills and the lack of taking time to ponder ideas. Cheating was the third most common concern, noting students using AI to fully complete assignments, not using it as a supportive tool, and the lack of citing use even when use is explicitly allowed and requested to be cited.

The next most common concern related to student’s lack of knowledge around AI use, including the targeted marketing of products to students. Respondents described students not understanding the need to verify the output, how and when to cite use, when it is appropriate to use, and what constitutes misuse. One respondent stated, “I do not believe my students have the ability to judiciously use AI in either a technical or ethical sense”. The final concern for students was related to the concept of learning through a mechanical voice. The respondents noted the lack of humanity in AI outputs and described students developing their written voice and communication style based on those outputs rather than human generated communications. There was also concern about diminishing creativity, lack of nuance and reasoning, and the process of thinking by getting the answer rather than thinking.

The AI-assisted analysis provided a summary of how the responses tracked to three major themes it identified. This summary was checked and verified by a human researcher. The AI was also able to identify specific and accurate quotes related to each theme after careful prompting and training.

| Theme (Claude.ai) | Count | Percentage |

| Theme 1: AI Limitations & Ethical Concerns | 98 | 29.4% |

| Theme 2: Academic Integrity & Misuse | 66 | 19.8% |

| Theme 3: Student Learning & Cognitive Development | 156 | 46.8% |

| No Concern | 12 | 3.6% |

| Other | 1 | 0.3% |

4.5.2 Benefits

Over 300 respondents wrote about the benefits of AI. Overwhelmingly present as a benefit (over 95 times) was the word and concept of efficiency for both faculty and students. AI was used by respondents to make workloads more manageable by offloading mundane tasks. Some respondents recommended students use AI to also offload tasks that are not required for learning to enhance their work. The need to prepare students for proper use while in school and real world application was also evident in the responses as was acknowledgment that respondents will have to be able to use it for their work. Respondents also report using AI to brainstorm ideas, for editing writing, as a jumpstart for research, as a collaborator to clarify assignments, and for summarizing content.

Accessibility in learning was another common theme. Respondents noted the ability to develop individualized learning plans, students’ ability to use AI as a learning tool with 24/7 support, and creating an equalizer when writing. One respondent wrote “when done intentionally and ethically, AI can act as a tool for accessibility and empowerment—helping students generate ideas, organize their thinking, or access feedback in ways that support diverse learning styles and needs.”

It is interesting to note that over 25 respondents specifically wrote that there is no benefit to using AI in their role.

The human and AI-assisted reviews again identified similar themes; however, the human review in this case was more nuanced. For example, the AI only counted 14 respondents as reporting no benefits, and its third theme had sparse support. More reinforcement training and spot checking could address this inter-rater reliability issue.

| Theme (Claude.ai) | Count | Percentage |

| Theme 1: Efficiency & Productivity

Time-saving, increased productivity, streamlining tasks, reducing workload |

165 | 47.6% |

| Theme 2: Enhanced Teaching & Learning

Brainstorming, idea generation, pedagogical value, preparing students for workforce, general teaching/learning benefits |

154 | 44.4% |

| Theme 3: Personalized Learning & Accessibility

Tailored tutoring, 24/7 support, individual feedback, adaptive learning, accessibility features |

14 | 4% |

| None: No Benefits | 14 | 4% |

4.6 Demographic and Institutional Differences

The survey revealed important variation across institutional contexts and demographic groups. Respondents’ experiences with AI are not uniform, and these differences highlight where targeted interventions may be most effective.

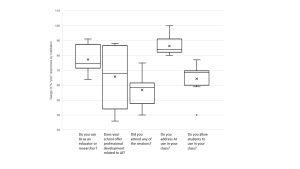

At the institutional level, variation between institutions was common among questions of AI usage, professional development opportunities, and allowing student usage. Most educators and researchers report using AI, with responses typically between 65% and 90%. Schools vary widely in faculty perceptions of professional development training on AI, ranging from about 35% awareness to nearly 90%. Fewer respondents attended these sessions, with most institutions showing 50–60% participation. Addressing AI use in class is relatively common, with responses clustered high around 80–100%. Allowing students to use AI in class is moderately accepted, with responses mostly between 60% and 75%, though one outlier institution is notably lower. Overall, the data suggest strong engagement with AI but uneven institutional support and policy consistency.

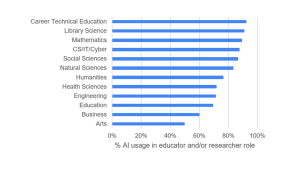

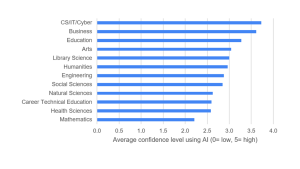

Disciplinary variation was more pronounced. Respondents in STEM and professional fields reported higher rates of adoption, though level of confidence varied across disciplines.

Interestingly, degree-program type had little impact on whether respondents allowed AI usage, with a variation between 65-72% permitting use.

Taken together, these findings underscore that respondents’ needs are diverse and context-dependent. Policy guidance and professional development should be sensitive to institutional type and discipline.

5. Expanded Discussion

The Idaho Higher Education Faculty Usage and Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Survey results reveal a faculty body that is neither uncritically embracing nor categorically rejecting AI. Instead, faculty are in the midst of a negotiation: balancing the efficiencies AI offers with the responsibilities of teaching, mentoring, and safeguarding academic standards. The results underscore several key themes:

Adoption outpacing confidence. Nearly half of respondents are using AI weekly, but only 30% report high confidence. This gap between adoption and assurance reflects innovation occurring faster than institutional support systems. Respondents are exploring AI pragmatically, but without consistent frameworks or coordinated expectations. This fragmented approach risks creating inconsistent learning experiences and underscores the need for statewide coherence in support, policy, and training. An additional concern is that respondents either lack confidence to use AI when it might be helpful, or they are overconfident in its outputs.

Professional development as a lever for adoption. The majority of respondents (64%) report access to AI-related training, but 23% are unaware if such opportunities exist, and 13% report no access. This suggests a communication gap rather than a lack of interest. Respondents want training that is hands-on, discipline-specific, and recurring, covering both technical skills and ethical implications. Many expressed frustration with one-off workshops and called for structured professional learning programs that evolve alongside the technology. Addressing this need would simultaneously raise confidence, improve teaching practice, and align institutional expectations.

Barriers reflect structural rather than attitudinal challenges. The top reasons for non-use indicate systemic gaps rather than respondent resistance. Respondents’ requests for policies, ethical guidance, and administrative clarity point to the absence of coordinated leadership. Addressing these barriers through clear standards, reliable tools, and protected time for faculty learning would translate directly into more confident and effective AI use.

Classroom practice as a site of experimentation. Most respondents (78%) already address AI use in their classes, and two-thirds allow students to use it for certain tasks. Respondents are, in effect, piloting AI policy from the bottom up. While this demonstrates adaptability and initiative, it also results in inconsistency: students may encounter different rules and expectations in each class or institution. However, it is also clear that different disciplines require unique approaches to AI pedagogy and utilization.

Ethical and pedagogical tensions at the core. Respondents’ concerns are deeply tied to teaching and learning, not just technology. Respondents worry that AI could diminish critical thinking, creativity, and academic integrity. They also express emotional fatigue at feeling pressure to adapt without adequate support. These concerns are not obstacles to progress but indicators of where leadership must focus: developing human-centered, ethically grounded approaches that ensure AI enhances rather than replaces core educational values.

Using AI in qualitative research. With respect to the role of AI in content analysis, large language models (LLMs) must be used with caution and should not replace human work. LLMs confidently hallucinate data and fabricate quotes. The most successful approach to using LLMs for content analysis involves retrieval augmented generation, careful human training of the AI tool on coding practices, specific prompting, and multiple “show your work” verification steps. Ultimately, Claude proved useful as an assistant but was not able to replace human work in content analysis. As a data analysis tool, LLMs remain most useful for experts and require some technical expertise to manage.

Idaho’s opportunity for statewide leadership. Idaho’s higher education system is at a strategic inflection point. Faculty s are eager to learn, experiment, and engage, but institutional systems have not yet matured to support sustained, ethical, and equitable AI use. The Idaho State Board of Education can play a defining role by facilitating statewide coordination, establishing common frameworks, and funding scalable, discipline-specific professional development. Taking these actions would move Idaho from fragmented experimentation to strategic leadership, positioning its institutions to leverage AI responsibly while preserving the human and pedagogical heart of education.

6. Recommendations

- Invest in Faculty Development:

- Fund scalable, discipline-specific training that emphasizes pedagogy, assessment, and ethical frameworks.

- Provide structured and scaffolded training ongoing rather than one-time professional development.

- Offer incentives such as stipends, course release, and/or recognition for participation.

- Coordinate with existing institutional teaching and learning centers to reduce duplication of effort.

- Encourage Responsible and Ethical Integration in Teaching and Learning:

- Establish clear principles for responsible AI use in curriculum, emphasizing transparency, critical thinking, and academic integrity.

- Encourage institutions to integrate AI ethics and literacy into general education outcomes.

- Expand teaching and learning centers to co-develop AI-enabled assignments, provide discipline-specific examples, and mentor faculty.

- Support Access to AI Tools and Infrastructure:

- Ensure that faculty across all Idaho institutions have equitable access to reliable AI tools, secure platforms, and technical support.

- Create a shared state repository or licensing pool for vetted AI tools that meet FERPA and accessibility standards.

- Encourage collaboration between research universities and community colleges through shared resource networks.

- Coordinate a Statewide AI in Higher Education Task Force:

- Establish a cross-institutional task force under the Idaho State Board of Education to coordinate implementation, track progress, and share best practices.

- Provide annual recommendations to the Board on progress, emerging needs, and ethical considerations.

- Position Idaho as a national leader in collaborative, responsible AI integration.

7. Conclusion

Faculty and instructional staff across Idaho are already using AI in meaningful ways, but confidence, clarity, and safe access remain challenges. The Idaho State Board of Education can play a pivotal role in ensuring that the state’s institutions move forward together, balancing innovation with responsibility. With clear guidance, structured training, and infrastructure, Idaho can become a national leader in responsible AI adoption in higher education.