15 Corporations and Securities

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the historical background of the corporation

- Compare the corporation to other business entities, including its liability shield

- Identify the rights, duties, and liability of shareholders, officers, and directors

- Understand the nature of securities regulation and the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

- Understand what insider trading is and why it is unlawful

Introduction to the Corporation

The corporation is the dominant form of the business enterprise in the modern world. As a legal entity, it is bound by much of the law discussed in the preceding chapters. However, as a significant institutional actor in the business world, the corporation has a host of relationships that have called forth a separate body of law.

Corporate History

Like partnership, the corporation is an ancient concept, recognized in the Code of Hammurabi, and to some degree a fixture in every other major legal system since then. The first corporations were not business enterprises; instead, they were associations for religious and governmental ends in which perpetual existence was a practical requirement. Thus until relatively late in legal history, kings, popes, and jurists assumed that corporations could be created only by political or ecclesiastical authority and that corporations were creatures of the state or church. By the seventeenth century, with feudalism on the wane and business enterprise becoming a growing force, kings extracted higher taxes and intervened more directly in the affairs of businesses by refusing to permit them to operate in corporate form except by royal grant.

The most important concessions, or charters, were those given to the giant foreign trading companies, including the Russia Company (1554), the British East India Company (1600), Hudson’s Bay Company (1670, and still operating in Canada under the name “the Bay”), and the South Sea Company (1711). These were joint-stock companies, that is, individuals contributed capital to the enterprise, which traded on behalf of all the stockholders. Originally, trading companies were formed for single voyages, but the advantages of a continuing fund of capital soon became apparent. Also apparent was the legal characteristic that above all led shareholders to subscribe to the stock: limited liability. They risked only the cash they put in, not their personal fortunes.

Some companies were wildly successful. The British East India Company paid its original investors a fourfold return between 1683 and 1692. But perhaps nothing excited the imagination of the British more than the discovery of gold bullion aboard a Spanish shipwreck; 150 companies were quickly formed to salvage the sunken Spanish treasure. Though most of these companies were outright frauds, they ignited the search for easy wealth by a public unwary of the risks. In particular, the South Sea Company promised the sun and the moon: in return for a monopoly over the slave trade to the West Indies, it told an enthusiastic public that it would retire the public debt and make every person rich.

In 1720, a fervor gripped London that sent stock prices soaring. Beggars and earls alike speculated from January to August; and then the bubble burst. Without considering the ramifications, Parliament had enacted the highly restrictive Bubble Act, which was supposed to do away with unchartered joint-stock companies. When the government prosecuted four companies under the act for having fraudulently obtained charters, the public panicked and stock prices came tumbling down, resulting in history’s first modern financial crisis.

As a consequence, corporate development was severely retarded in England. Distrustful of the chartered company, Parliament issued few corporate charters, and then only for public or quasi-public undertakings, such as transportation, insurance, and banking enterprises. England did not repeal the Bubble Act until 1825, and then only because the value of true incorporation had become apparent from the experience of its former colonies.

The United States remained largely unaffected by the Bubble Act. Incorporation was granted only by special acts of state legislatures, even well into the nineteenth century, but many such acts were passed. Before the Revolution, perhaps fewer than a dozen business corporations existed throughout the thirteen colonies. During the 1790s, two hundred businesses were incorporated, and their numbers swelled thereafter. The theory that incorporation should not be accomplished except through special legislation began to give way. As industrial development accelerated in the mid-1800s, it was possible in many states to incorporate by adhering to the requirements of a general statute. Indeed, by the late nineteenth century, all but three states constitutionally forbade their legislatures from chartering companies through special enactments.

Following World War II, most states revised their general corporation laws. A significant development for states was the preparation of the Model Business Corporation Act by the American Bar Association’s Committee on Corporate Laws. About half of the states have adopted all or major portions of the act. The 2005 version of this act, the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA), will be referred to throughout our discussion of corporation law.

Types of Corporations

Nonprofit Corporations

One of the four major classifications of corporations is the nonprofit corporation (also called not-for-profit corporation). It is defined in the American Bar Association’s Model Non-Profit Corporation Act as “a corporation no part of the income of which is distributable to its members, directors or officers.” Nonprofit corporations may be formed under this law for charitable, educational, civil, religious, social, and cultural purposes, among others.

Public Corporations

The true public corporation is a governmental entity. It is often called a municipal corporation, to distinguish it from the publicly held corporation, which is sometimes also referred to as a “public” corporation, although it is in fact private (i.e., it is not governmental). Major cities and counties, and many towns, villages, and special governmental units, such as sewer, transportation, and public utility authorities, are incorporated. These corporations are not organized for profit, do not have shareholders, and operate under different statutes than do business corporations.

Professional Corporations

Until the 1960s, lawyers, doctors, accountants, and other professionals could not practice their professions in corporate form. This inability, based on a fear of professionals’ being subject to the direction of the corporate owners, was financially disadvantageous. Under the federal income tax laws then in effect, corporations could establish far better pension plans than could the self-employed. During the 1960s, the states began to let professionals incorporate, but the IRS balked, denying them many tax benefits. In 1969, the IRS finally conceded that it would tax a professional corporation just as it would any other corporation, so that professionals could, from that time on, place a much higher proportion of tax-deductible income into a tax-deferred pension. That decision led to a burgeoning number of professional corporations.

Business Corporations

It is the business corporation proper that we focus on in this unit. There are two broad types of business corporations: publicly held (or public) and closely held (or close or private) corporations. Again, both types are private in the sense that they are not governmental.

The publicly held corporation is one in which stock is widely held or available for wide public distribution through such means as trading on a national or regional stock exchange. Its managers, if they are also owners of stock, usually constitute a small percentage of the total number of shareholders and hold a small amount of stock relative to the total shares outstanding. Few, if any, shareholders of public corporations know their fellow shareholders.

By contrast, the shareholders of the closely held corporation are fewer in number. Shares in a closely held corporation could be held by one person, and usually by no more than thirty. Shareholders of the closely held corporation often share family ties or have some other association that permits each to know the others.

Though most closely held corporations are small, no economic or legal reason prevents them from being large. Some are huge, having annual sales of several billion dollars each. Roughly 90 percent of US corporations are closely held.

The giant publicly held companies with more than $1 billion in assets and sales, with initials such as IBM and GE, constitute an exclusive group. Publicly held corporations outside this elite class fall into two broad (nonlegal) categories: those that are quoted on stock exchanges and those whose stock is too widely dispersed to be called closely held but is not traded on exchanges.

Finally, many states now allow corporations to legally organize as public benefit corporations. These entities incorporate specific social or environmental responsibilities into their legal structure. This allows the corporation to pursue public benefit without risking lawsuits alleging failure to maximize shareholder profit. An example of a benefit corporation is King Arthur Flour, a for-profit entity devoted to a social mission of encouraging home baking.

Forming a Corporation

Partnerships are easy to form. If the business is simple enough and the partners are few, the agreement need not even be written down. Creating a corporation is more complicated because formal documents must be placed on file with public authorities.

The ultimate goal of the incorporation process is issuance of a corporate charter. The term used for the document varies from state to state. Most states call the basic document filed in the appropriate public office the “articles of incorporation” or “certificate of incorporation,” but there are other variations. There is no legal significance to these differences in terminology.

Chartering is basically a state prerogative. Congress has chartered several enterprises, including national banks (under the National Banking Act), federal savings and loan associations, national farm loan associations, and the like, but virtually all business corporations are chartered at the state level.

Originally a legislative function, chartering is now an administrative function in every state. The secretary of state issues the final indorsement to the articles of incorporation, thus giving them legal effect.

Where to Charter

Choosing the particular venue in which to incorporate is the first critical decision to be made after deciding to incorporate. Some corporations, though headquartered in the United States, choose to incorporate offshore to take advantage of lenient taxation laws. Advantages of an offshore corporation include not only lenient tax laws but also a great deal of privacy as well as certain legal protections. For example, the names of the officers and directors can be excluded from documents filed. In the United States, over half of the Fortune 500 companies hold Delaware charters for reasons related to Delaware’s having a lower tax structure, a favorable business climate, and a legal system—both its statutes and its courts—seen as being up to date, flexible, and often probusiness. Delaware’s success has led other states to compete, and the political realities have caused the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA), which was intentionally drafted to balance the interests of all significant groups (management, shareholders, and the public), to be revised from time to time so that it is more permissive from the perspective of management.

Delaware remains the most popular state in which to incorporate for several reasons, including the following: (1) low incorporation fees; (2) only one person is needed to serve the incorporator of the corporation; the RMBC requires three incorporators; (3) no minimum capital requirement; (4) favorable tax climate, including no sales tax; (5) no taxation of shares held by nonresidents; and (5) no corporate income tax for companies doing business outside of Delaware. In addition, Delaware’s Court of Chancery, a court of equity, is renowned as a premier business court with a well-established body of corporate law, thereby affording a business a certain degree of predictability in judicial decision making.

Promoters

Once the state of incorporation has been selected, it is time for promoters, the midwives of the enterprise, to go to work. Promoters are the individuals who take the steps necessary to form the corporation, and they often will receive stock in exchange for their efforts. They have four principal functions: (1) to seek out or discover business opportunities, (2) to raise capital by persuading investors to sign stock subscriptions, (3) to enter into contracts on behalf of the corporation to be formed, (4) and to prepare the articles of incorporation.

Promoters have acquired an unsavory reputation as fast talkers who cajole investors out of their money. Though some promoters fit this image, it is vastly overstated. Promotion is difficult work often carried out by the same individuals who will manage the business.

Promoters face two major legal problems. First, they face possible liability on contracts made on behalf of the business before it is incorporated. For example, suppose Bob is acting as promoter of the proposed BCT Bookstore, Inc. On September 15, he enters into a contract with Computogram Products to purchase computer equipment for the corporation to be formed. If the incorporation never takes place, or if the corporation is formed but the corporation refuses to accept the contract, Bob remains liable.

The promoters’ other major legal concern is the duty owed to the corporation. The law is clear that promoters owe a fiduciary duty. For example, a promoter who transfers real estate worth $250,000 to the corporation in exchange for $750,000 worth of stock would be liable for $500,000 for breach of fiduciary duty.

Articles of Incorporation

Once the business details are settled, the promoters, now known as incorporators, must sign and deliver the articles of incorporation to the secretary of state. The articles of incorporation typically include the following: the corporate name; the address of the corporation’s initial registered office; the period of the corporation’s duration (usually perpetual); the company’s purposes; the total number of shares, the classes into which they are divided, and the par value of each; the limitations and rights of each class of shareholders; the authority of the directors to establish preferred or special classes of stock; provisions for preemptive rights; provisions for the regulation of the internal affairs of the corporation, including any provision restricting the transfer of shares; the number of directors constituting the initial board of directors and the names and addresses of initial members; and the name and address of each incorporator. Although compliance with these requirements is largely a matter of filling in the blanks, two points deserve mention.

First, the choice of a name is often critical to the business. Under RMBCA, Section 4.01, the name must include one of the following words (or abbreviations): corporation, company, incorporated, or limited (Corp., Co., Inc., or Ltd.). The name is not allowed to deceive the public about the corporation’s purposes, nor may it be the same as that of any other company incorporated or authorized to do business in the state.

These legal requirements are obvious; the business requirements are much harder. If the name is not descriptive of the business or does not anticipate changes in the business, it may have to be changed, and the change can be expensive. For example, when Standard Oil Company of New Jersey changed its name to Exxon in 1972, the estimated cost was over $100 million. (And even with this expenditure, some shareholders grumbled that the new name sounded like a laxative.)

The second point to bear in mind about the articles of incorporation is that drafting the clause stating corporate purposes requires special care, because the corporation will be limited to the purposes set forth. In one famous case, the charter of Cornell University placed a limit on the amount of contributions it could receive from any one benefactor. When Jennie McGraw died in 1881, leaving to Cornell the carillon that still plays on the Ithaca, New York, campus to this day, she also bequeathed to the university her residuary estate valued at more than $1 million. This sum was greater than the ceiling placed in Cornell’s charter. After lengthy litigation, the university lost in the US Supreme Court, and the money went to her family.[1] The dilemma is how to draft a clause general enough to allow the corporation to expand, yet specific enough to prevent it from engaging in undesirable activities.

Some states require the purpose clauses to be specific, but the usual approach is to permit a broad statement of purposes. Section 3.01 of the RMBCA goes one step further in providing that a corporation automatically “has the purpose of engaging in any lawful business” unless the articles specify a more limited purpose. Once completed, the articles of incorporation are delivered to the secretary of state for filing. The existence of a corporation begins once the articles have been filed.

The first order of business, once the certificate of incorporation is issued, is a meeting of the board of directors named in the articles of incorporation. They must adopt bylaws, elect officers, and transact any other business that may come before the meeting (RMBCA, Section 2.05). Other business would include accepting (ratifying) promoters’ contracts, calling for the payment of stock subscriptions, and adopting bank resolution forms, giving authority to various officers to sign checks drawn on the corporation.

If promoters meet the requirements of corporate formation, a de jure corporation, considered a legal entity, is formed. Because the various steps are complex, the formal prerequisites are not always met. Suppose that a company, thinking its incorporation has taken place when in fact it hasn’t met all requirements, starts up its business. What then? Is everything it does null and void? If three conditions exist, a court might decide that a de facto corporation has been formed; that is, the business will be recognized as a corporation. The state then has the power to force the de facto corporation to correct the defect(s) so that a de jure corporation will be created.

The three traditional conditions are the following: (1) a statute must exist under which the corporation could have been validly incorporated, (2) the promoters must have made a bona fide attempt to comply with the statute, and (3) corporate powers must have been used or exercised.

A frequent cause of defective incorporation is the promoters’ failure to file the articles of incorporation in the appropriate public office. The states are split on whether a de facto corporation results if every other legal requirement is met.

Running a Corporation

Power within a corporation is present in many areas. The corporation itself has powers, although with limitations. There is a division of power between shareholders, directors, and officers. Given this division of power, certain duties are owed amongst the parties. We focus this section upon these powers and upon the duties owed by shareholders, directors, and officers.

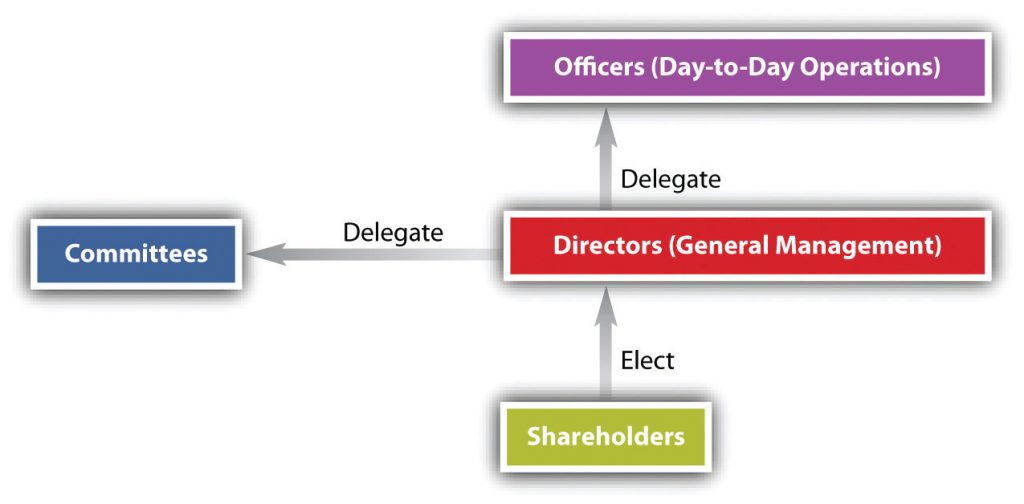

A corporation generally has three parties sharing power and control: directors, officers, and shareholders. Directors are the managers of the corporation and have legal responsibility for it, and officers control the day-to-day decisions and work more closely with the employees. The shareholders are the owners of the corporation, but they have little decision-making authority.

Directors and Officers

Directors derive their power to manage the corporation from statutory law. Section 8.01 of the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA) states that “all corporate powers shall be exercised by or under the authority of, and the business and affairs of the corporation managed under the direction of, its board of directors.” A director is a fiduciary, a person to whom power is entrusted for another’s benefit, and as such, as the RMBCA puts it, must perform his duties “in good faith, with the care an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would exercise under similar circumstances” (Section 8.30). A director’s main responsibilities include the following: (1) to protect shareholder investments, (2) to select and remove officers, (3) to delegate operating authority to the managers or other groups, and (4) to supervise the company as a whole.

Under RMBCA Section 8.25, the board of directors, by majority vote, may delegate its powers to various committees. This authority is limited to some degree. For example, only the full board can determine dividends, approve a merger, and amend the bylaws. The delegation of authority to a committee does not, by itself, relieve a director from the duty to exercise due care.

The directors often delegate to officers the day-to-day authority to execute the policies established by the board and to manage the firm. Normally, the president is the chief executive officer (CEO) to whom all other officers and employees report, but sometimes the CEO is also the chairman of the board.

Shareholders

In the modern publicly held corporation, ownership and control are separated. The shareholders “own” the company through their ownership of its stock, but power to manage is vested in the directors. In a large publicly traded corporation, most of the ownership of the corporation is diluted across its numerous shareholders, many of whom have no involvement with the corporation other than through their stock ownership. On the other hand, the issue of separation and control is generally irrelevant to the closely held corporation, since in many instances the shareholders are the same people who manage and work for the corporation.

Shareholders do retain some degree of control. For example, they elect the directors, although only a small fraction of shareholders control the outcome of most elections because of the diffusion of ownership and modern proxy rules; proxy fights are extremely difficult for insurgents to win. Shareholders also may adopt, amend, and repeal the corporation’s bylaws; they may adopt resolutions ratifying or refusing to ratify certain actions of the directors. And they must vote on certain extraordinary matters, such as whether to amend the articles of incorporation, merge, or liquidate.

In most states, the corporation must hold at least one meeting of shareholders each year. The board of directors or shareholders representing at least 10 percent of the stock may call a special shareholders’ meeting at any time unless a different threshold number is stated in the articles or bylaws. Timely notice is required: not more than sixty days nor less than ten days before the meeting, under Section 7.05 of the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA). Shareholders may take actions without a meeting if every shareholder entitled to vote consents in writing to the action to be taken. This option is obviously useful to the closely held corporation but not to the giant publicly held companies.

Shareholder Voting

Through its bylaws or by resolution of the board of directors, a corporation can set a “record date.” Only the shareholders listed on the corporate records on that date receive notice of the next shareholders’ meeting and have the right to vote. Every share is entitled to one vote unless the articles of incorporation state otherwise.

The one-share, one-vote principle, commonly called regular voting or statutory voting, is not required, and many US companies have restructured their voting rights in an effort to repel corporate raiders. For instance, a company might decide to issue both voting and nonvoting shares, with the voting shares going to insiders who thereby control the corporation.

When the articles of incorporation are silent, a shareholder quorum is a simple majority of the shares entitled to vote, whether represented in person or by proxy, according to RMBCA Section 7.25. Thus if there are 1 million shares, 500,001 must be represented at the shareholder meeting. A simple majority of those represented shares is sufficient to carry any motion, so 250,001 shares are enough to decide upon a matter other than the election of directors (governed by RMBCA, Section 7.28). The articles of incorporation may decree a different quorum but not less than one-third of the total shares entitled to vote.

Cumulative voting^[Shareholder voting method permitting the holder to distribute his total votes in any manner that he chooses—all for one candidate or several shares for different candidates.] means that a shareholder may distribute his total votes in any manner that he chooses—all for one candidate or several shares for different candidates. With cumulative voting, each shareholder has a total number of votes equal to the number of shares he owns multiplied by the number of directors to be elected. Thus if a shareholder has 1,000 shares and there are five directors to be elected, the shareholder has 5,000 votes, and he may vote those shares in a manner he desires (all for one director, or 2,500 each for two directors, etc.). Some states permit this right unless the articles of incorporation deny it. Other states deny it unless the articles of incorporation permit it. Several states have constitutional provisions requiring cumulative voting for corporate directors.

Cumulative voting is meant to provide minority shareholders with representation on the board. Assume that Bob and Carol each owns 2,000 shares, which they have decided to vote as a block, and Ted owns 6,000 shares. At their annual shareholder meeting, they are to elect five directors. Without cumulative voting, Ted’s slate of directors would win: under statutory voting, each share represents one vote available for each director position. With this method, by placing as many votes as possible for each director, Ted could cast 6,000 votes for each of his desired directors. Thus each of Ted’s directors would receive 6,000 votes, while each of Bob and Carol’s directors would receive only 4,000. Under cumulative voting, however, each shareholder has as many votes as there are directors to be elected. Hence with cumulative voting Bob and Carol could strategically distribute their 20,000 votes (4,000 votes multiplied by five directors) among the candidates to ensure representation on the board. By placing 10,000 votes each on two of their candidates, they would be guaranteed two positions on the board. (The candidates from the two slates are not matched against each other on a one-to-one basis; instead, the five candidates with the highest number of votes are elected.) Various formulas and computer programs are available to determine how votes should be allocated, but the principle underlying the calculations is this: cumulative voting is democratic in that it allows the shareholders who own 40 percent of the stock—Bob and Carol—to elect 40 percent of the board.

Proxies

A proxy is the representative of the shareholder. A proxy may be a person who stands in for the shareholder or may be a written instrument by which the shareholder casts her votes before the shareholder meeting. Modern proxy voting allows shareholders to vote electronically through the internet. Proxies are usually solicited by and given to management, either to vote for proposals or people named in the proxy or to vote however the proxy holder wishes. Through the proxy device, management of large companies can maintain control over the election of directors. Proxies must be signed by the shareholder and are valid for eleven months from the time they are received by the corporation unless the proxy explicitly states otherwise. Management may use reasonable corporate funds to solicit proxies if corporate policy issues are involved, but misrepresentations in the solicitation can lead a court to nullify the proxies and to deny reimbursement for the solicitation cost. Only the last proxy given by a particular shareholder can be counted.

Proxy solicitations are regulated by the SEC. For instance, SEC rules require companies subject to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to file proxy materials with the SEC at least ten days before proxies are mailed to shareholders. Proxy statements must disclose all material facts, and companies must use a proxy form on which shareholders can indicate whether they approve or disapprove of the proposals.

Key Takeaways

Corporations have their roots in political and religious authority. The concept of limited liability and visions of financial rewards fueled the popularity of joint-stock companies, particularly trading companies, in late-seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century England. The English Parliament successfully enacted the Bubble Act in 1720 to curb the formation of these companies; the restrictions weren’t loosened until over one hundred years later, after England viewed the success of corporations in its former colonies. Although early corporate laws in the United States were fairly restrictive, once states began to “sell” incorporation for tax revenues, the popularity of liberal and corporate-friendly laws caught on, especially in Delaware beginning in 1899. A corporation remains a creature of the state—that is, the state in which it is incorporated. Delaware remains the state of choice because more corporations are registered there than in any other state.

Articles of incorporation represent a corporate charter—that is, a contract between the corporation and the state. Filing these articles, or “chartering,” is accomplished at the state level. The secretary of state’s final approval gives these articles legal effect. A state cannot change a charter unless it reserves the right when granting the charter.In selecting a state in which to incorporate, a corporation looks for a favorable corporate climate. Delaware remains the state of choice for incorporation, particularly for publicly held companies. Most closely held companies choose to incorporate in their home states.

A court will find that a corporation might exist under fact (de facto), and not under law (de jure) if the following conditions are met: (1) a statute exists under which the corporation could have been validly incorporated, (2) the promoters must have made a bona fide attempt to comply with the statute, and (3) corporate powers must have been used or exercised. A de facto corporation may also be found when a promoter fails to file the articles of incorporation.

Liability Rules for Corporations

Director Liability and the Business Judgment Rule

Not so long ago, boards of directors of large companies were quiescent bodies, virtual rubber stamps for their friends among management who put them there. By the late 1970s, with the general increase in the climate of litigiousness, one out of every nine companies on the Fortune 500 list saw its directors or officers hit with claims for violation of their legal responsibilities.“[2] In a seminal case, the Delaware Supreme Court found that the directors of TransUnion were grossly negligent in accepting a buyout price of $55 per share without sufficient inquiry or advice on the adequacy of the price, a breach of their duty of care owed to the shareholders. The directors were held liable for $23.5 million for this breach.[3] Thus serving as a director or an officer was never free of business risks. Today, the task is fraught with legal risk as well.

Two main fiduciary duties apply to both directors and officers: one is a duty of loyalty, the other the duty of care. These duties arise from responsibilities placed upon directors and officers because of their positions within the corporation. The requirements under these duties have been refined over time. Courts and legislatures have both narrowed the duties by defining what is or is not a breach of each duty and have also expanded their scope.

Duty of Loyalty

As a fiduciary of the corporation, the director owes his primary loyalty to the corporation and its stockholders, as do the officers and majority shareholders. This responsibility is called the duty of loyalty. When there is a conflict between a director’s personal interest and the interest of the corporation, he is legally bound to put the corporation’s interest above his own.

The law does not bar a director from contracting with the corporation he serves. However, unless the contract or transaction is “fair to the corporation,” Sections 8.61, 8.62, and 8.63 of the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA) impose on him a stringent duty of disclosure. In the absence of a fair transaction, a contract between the corporation and one of its directors is voidable. If the transaction is unfair to the corporation, it may still be permitted if the director has made full disclosure of his personal relationship or interest in the contract and if disinterested board members or shareholders approve the transaction.

Whenever a director or officer learns of an opportunity to engage in a variety of activities or transactions that might be beneficial to the corporation, his first obligation is to present the opportunity to the corporation. The rule encompasses the chance of acquiring another corporation, purchasing property, and licensing or marketing patents or products.

Duty of Care

The second major aspect of the director’s responsibility is that of duty of care. Section 8.30 of RMBCA calls on the director to perform his duties “with the care an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would exercise under similar circumstances.” An “ordinarily prudent person” means one who directs his intelligence in a thoughtful way to the task at hand. Put another way, a director must make a reasonable effort to inform himself before making a decision, as discussed in the next paragraph. The director is not held to a higher standard required of a specialist (finance, marketing) unless he is one. A director of a small, closely held corporation will not necessarily be held to the same standard as a director who is given a staff by a large, complex, diversified company. The standard of care is that which an ordinarily prudent person would use who is in “a like position” to the director in question. Moreover, the standard is not a timeless one for all people in the same position. The standard can depend on the circumstances: a fast-moving situation calling for a snap decision will be treated differently later, if there are recriminations because it was the wrong decision, than a situation in which time was not of the essence.

What of the care itself? What kind of care would an ordinarily prudent person in any situation be required to give? Unlike the standard of care, which can differ, the care itself has certain requirements. At a minimum, the director must pay attention. He must attend meetings, receive and digest information adequate to inform him about matters requiring board action, and monitor the performance of those to whom he has delegated the task of operating the corporation. Of course, documents can be misleading, reports can be slanted, and information coming from self-interested management can be distorted. To what heights must suspicion be raised? Section 8.30 of the RMBCA forgives directors the necessity of playing detective whenever information, including financial data, is received in an apparently reliable manner from corporate officers or employees or from experts such as attorneys and public accountants. Thus the director does not need to check with another attorney once he has received financial data from one competent attorney.

Despite the fiduciary requirements, in reality a director does not spend all his time on corporate affairs, is not omnipotent, and must be permitted to rely on the word of others. Nor can directors be infallible in making decisions. Managers work in a business environment, in which risk is a substantial factor. No decision, no matter how rigorously debated, is guaranteed. Accordingly, courts will not second-guess decisions made on the basis of good-faith judgment and due care. This is the business judgment rule. As described by the Delaware Supreme Court: “The business judgment rule is an acknowledgment of the managerial prerogatives of Delaware directors.…It is a presumption that in making a business decision the directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the company.”[4]

Under the business judgment rule, the actions of directors who fulfill their fiduciary duties will not be second-guessed by a court. The general test is whether a director’s decision or transaction was so one sided that no businessperson of ordinary judgment would reach the same decision.

Shareholder Derivative Suits

If a shareholder is not pleased by a director’s decision, that shareholder may file a derivative suit. The derivative suit may be filed by a shareholder on behalf of the corporation against directors or officers of the corporation, alleging breach of their fiduciary obligations. Although the corporation is named as a defendant in the suit, the corporation itself is the so-called real party in interest—the party entitled to recover if the plaintiff wins. However, a shareholder, as a prerequisite to filing a derivative action, must first demand that the board of directors take action, as the actual party in interest is the corporation, not the shareholder (meaning that if the shareholder is victorious in the lawsuit, it is actually the corporation that “wins”). If the board refuses, is its decision protected by the business judgment rule? The general rule is that the board may refuse to file a derivative suit and will be protected by the business judgment rule. And even when a derivative suit is filed, directors can be protected by the business judgment rule for decisions even the judge considers to have been poorly made.

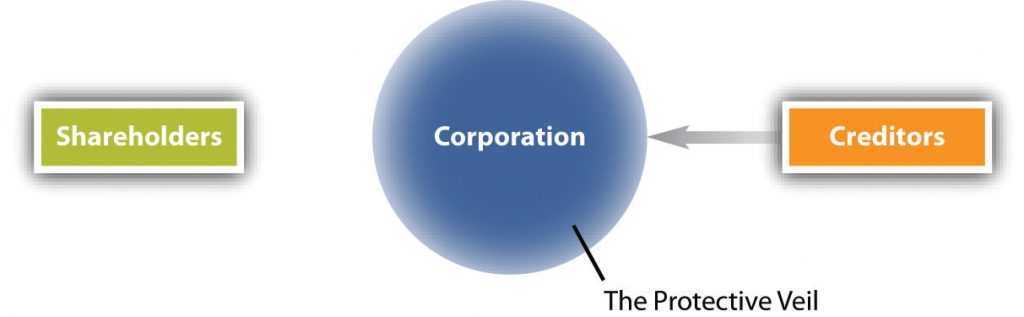

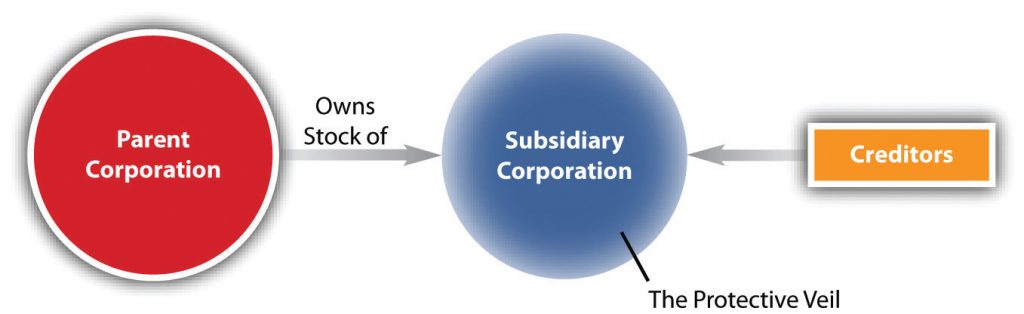

Piercing the Corporate Veil

In comparing partnerships and corporations, there is one additional factor that ordinarily tips the balance in favor of incorporating: the corporation is a legal entity in its own right, one that can provide a “veil” that protects its shareholders from personal liability.

This crucial factor accounts for the development of much of corporate law. Unlike the individual actor in the legal system, the corporation is difficult to deal with in conventional legal terms. The business of the sole proprietor and the sole proprietor herself are one and the same. When a sole proprietor makes a decision, she risks her own capital. When the managers of a corporation take a corporate action, they are risking the capital of others—the shareholders. Thus accountability is a major theme in the system of law constructed to cope with legal entities other than natural persons.

Given the importance of the corporate entity as a veil that limits shareholder liability, it is important to note that in certain circumstances, the courts may reach beyond the wall of protection that divides a corporation from the people or entities that exist behind it. This is known as piercing the corporate veil, and it will occur in two instances: (1) when the corporation is used to commit a fraud or an injustice and (2) when the corporation does not act as if it were one.

Fraud

The Felsenthal Company burned to the ground. Its president, one of the company’s largest creditors and also virtually its sole owner, instigated the fire. The corporation sued the insurance company to recover the amount for which it was insured. According to the court in the Felsenthal case, “The general rule of law is that the willful burning of property by a stockholder in a corporation is not a defense against the collection of the insurance by the corporation, and…the corporation cannot be prevented from collecting the insurance because its agents willfully set fire to the property without the participation or authority of the corporation or of all of the stockholders of the corporation.”[5] But because the fire was caused by the beneficial owner of “practically all” the stock, who also “has the absolute management of [the corporation’s] affairs and its property, and is its president,” the court refused to allow the company to recover the insurance money; allowing the company to recover would reward fraud.[6]

Failure to Act as a Corporation

In other limited circumstances, individual stockholders may also be found personally liable. Failure to follow corporate formalities, for example, may subject stockholders to personal liability.[7] This is a special risk that small, especially one-person, corporations run. Particular factors that bring this rule into play include inadequate capitalization, omission of regular meetings, failure to record minutes of meetings, failure to file annual reports, and commingling of corporate and personal assets. Where these factors exist, the courts may look through the corporate veil and pluck out the individual stockholder or stockholders to answer for a tort, contract breach, or the like. The classic case is the taxicab operator who incorporates several of his cabs separately and services them through still another corporation. If one of the cabs causes an accident, the corporation is usually “judgment proof” because the corporation will have few assets (practically worthless cab, minimum insurance). The courts frequently permit plaintiffs to proceed against the common owner on the grounds that the particular corporation was inadequately financed.

Even when a corporation is formed for a proper purpose and is operated as a corporation, there are instances in which individual shareholders will be personally liable. For example, if a shareholder involved in company management commits a tort or enters into a contract in a personal capacity, he will remain personally liable for the consequences of his actions. In some states, statutes give employees special rights against shareholders. For example, a New York statute permits employees to recover wages, salaries, and debts owed them by the company from the ten largest shareholders of the corporation. (Shareholders of public companies whose stock is traded on a national exchange or over the counter are exempt.) Likewise, federal law permits the IRS to recover from the “responsible persons” any withholding taxes collected by a corporation but not actually paid over to the US Treasury.

Securities Regulation: the 1933 and 1934 Acts

Corporate finance is a heavily regulated and policed area of the law. For example, stock issued by a corporation to raise capital counts as a “security” under federal law. Both the registration and the trading of securities are highly regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). A violation of a securities law can lead to severe criminal and civil penalties.

The Nature of Securities Regulation

What we commonly refer to as “securities” are essentially worthless pieces of paper. Their inherent value lies in the interest in property or an ongoing enterprise that they represent. This disparity between the tangible property—the stock certificate, for example—and the intangible interest it represents gives rise to several reasons for regulation. First, there is need for a mechanism to inform the buyer accurately what it is he is buying. Second, laws are necessary to prevent and provide remedies for deceptive and manipulative acts designed to defraud buyers and sellers. Third, the evolution of stock trading on a massive scale has led to the development of numerous types of specialists and professionals, in dealings with whom the public can be at a severe disadvantage, and so the law undertakes to ensure that they do not take unfair advantage of their customers.

The Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 are two federal statutes that are vitally important, having virtually refashioned the law governing corporations during the past half century. In fact, it is not too much to say that although they deal with securities, they have become the general federal law of corporations.

What is a Security

Securities law questions are technical and complex and usually require professional counsel. For the nonlawyer, the critical question on which all else turns is whether the particular investment or document is a security.^[Any note, stock, treasury stock, bond, debenture, evidence of indebtedness, certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement, collateral-trust certificate, or subscription, transferable share, investment contract, voting-trust certificate, certificate of deposit for a security, fractional undivided interest in oil, gas, or other mineral rights, or, in general, any interest or instrument commonly known as a security.] If it is, anyone attempting any transaction beyond the routine purchase or sale through a broker should consult legal counsel to avoid the various civil and criminal minefields that the law has strewn about.

The definition of security, which is set forth in the Securities Act of 1933, is comprehensive, but it does not on its face answer all questions that financiers in a dynamic market can raise. Under Section 2(1) of the act, “security” includes “any note, stock, treasury stock, bond, debenture, evidence of indebtedness, certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement, collateral-trust certificate, preorganization certificate or subscription, transferable share, investment contract, voting-trust certificate, certificate of deposit for a security, fractional undivided interest in oil, gas, or other mineral rights, or, in general, any interest or instrument commonly known as a ‘security,’ or any certificate of interest or participation in, temporary or interim certificate for, receipt for, guarantee of, or warrant or right to subscribe to or purchase, any of the foregoing.”

Under this definition, an investment may not be a security even though it is so labeled, and it may actually be a security even though it is called something else. For example, does a service contract that obligates someone who has sold individual rows in an orange orchard to cultivate, harvest, and market an orange crop involve a security subject to regulation under federal law? Yes, said the Supreme Court in _Securities & Exchange Commission v. W. J. Howey Co._Securities & Exchange Commission v. W. J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293 (1946). The Court said the test is whether “the person invests his money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party.” Under this test, courts have liberally interpreted “investment contract^[A commitment of money or capital to purchase financial instruments as a means to gain profitable returns in the form of income, interest, or the appreciation of the value of the instrument itself. It can be interpreted by the courts to be a security for purposes of the federal securities laws.”] and “certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement” to be securities interests in such property as real estate condominiums and cooperatives, commodity option contracts, and farm animals.

The SEC

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is over half a century old, having been created by Congress in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. It is an independent regulatory agency, subject to the rules of the Administrative Procedure Act (see Chapter 5 “Administrative Law”). The commission is composed of five members, who have staggered five-year terms. Every June 5, the term of one of the commissioners expires. Although the president cannot remove commissioners during their terms of office, he does have the power to designate the chairman from among the sitting members. The SEC is bipartisan: not more than three commissioners may be from the same political party.

The SEC’s primary task is to investigate complaints or other possible violations of the law in securities transactions and to bring enforcement proceedings when it believes that violations have occurred. It is empowered to conduct information inquiries, interview witnesses, examine brokerage records, and review trading data. If its requests are refused, it can issue subpoenas and seek compliance in federal court. Its usual leads come from complaints of investors and the general public, but it has authority to conduct surprise inspections of the books and records of brokers and dealers. Another source of leads is price fluctuations that seem to have been caused by manipulation rather than regular market forces.

Among the violations the commission searches out are these: (1) unregistered sale of securities subject to the registration requirement of the Securities Act of 1933, (2) fraudulent acts and practices, (3) manipulation of market prices, (4) carrying out of a securities business while insolvent, (5) misappropriation of customers’ funds by brokers and dealers, and (4) other unfair dealings by brokers and dealers.

Securities Act of 1933

The Securities Act of 1933^[The first law enacted by Congress to regulate the securities market. This act regulates the public offering of new securities and provides for securities registration requirements, and prevention of fraudulent conduct.] is the fundamental “truth in securities” law. Its two basic objectives, which are written in its preamble, are “to provide full and fair disclosure of the character of securities sold in interstate and foreign commerce and through the mails, and to prevent frauds in the sale thereof.”

The primary means for realizing these goals is the requirement of registration. Before securities subject to the act can be offered to the public, the issuer must file a registration statement and prospectus with the SEC, laying out in detail relevant and material information about the offering as set forth in various schedules to the act. If the SEC approves the registration statement, the issuer must then provide any prospective purchaser with the prospectus. Since the SEC does not pass on the fairness of price or other terms of the offering, it is unlawful to state or imply in the prospectus that the commission has the power to disapprove securities for lack of merit, thereby suggesting that the offering is meritorious.

The SEC has prepared special forms for registering different types of issuing companies. All call for a description of the registrant’s business and properties and of the significant provisions of the security to be offered, facts about how the issuing company is managed, and detailed financial statements certified by independent public accountants.

Once filed, the registration and prospectus become public and are open for public inspection. Ordinarily, the effective date of the registration statement is twenty days after filing. Until then, the offering may not be made to the public. Section 2(10) of the act defines prospectus as any “notice, circular, advertisement, letter, or communication, written or by radio or television, which offers any security for sale or confirms the sale of any security.” (An exception: brief notes advising the public of the availability of the formal prospectus.) The import of this definition is that any communication to the public about the offering of a security is unlawful unless it contains the requisite information.

The SEC staff examines the registration statement and prospectus, and if they appear to be materially incomplete or inaccurate, the commission may suspend or refuse the effectiveness of the registration statement until the deficiencies are corrected. Even after the securities have gone on sale, the agency has the power to issue a stop order that halts trading in the stock.

Section 24 of the Securities Act of 1933 provides for fines not to exceed $10,000 and a prison term not to exceed five years, or both, for willful violations of any provisions of the act. This section makes these criminal penalties specifically applicable to anyone who “willfully, in a registration statement filed under this title, makes any untrue statement of a material fact or omits to state any material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading.”

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934

The Securities Act of 1933 is limited, as we have just seen, to new securities issues—that is the primary market. The trading that takes place in the secondary market is far more significant, however. In a normal year, trading in outstanding stock totals some twenty times the value of new stock issues.

To regulate the secondary market, Congress enacted the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.^[A law that was enacted to provide governance of securities transactions on the secondary market and to regulate the exchanges and broker-dealers in order to protect the investing public. This act also established the SEC.] This law, which created the SEC, extended the disclosure rationale to securities listed and registered for public trading on the national securities exchanges. Amendments to the act have brought within its ambit every corporation whose equity securities are traded over the counter if the company has at least $10 million in assets and five hundred or more shareholders.

Private investors may bring suit in federal court for violations of the statute that led to financial injury. Violations of any provision and the making of false statements in any of the required disclosures subject the defendant to a maximum fine of $5 million and a maximum twenty-year prison sentence, but a defendant who can show that he had no knowledge of the particular rule he was convicted of violating may not be imprisoned. The maximum fine for a violation of the act by a person other than a natural person is $25 million. Any issuer omitting to file requisite documents and reports is liable to pay a fine of $100 for each day the failure continues.

Insider Trading

Corporate insiders^[A corporate director, officer, or shareholder with more than 10 percent of a registered security who through influence of position obtains knowledge that may be used to gain an unfair advantage to the detriment of others. The definition has been broadened to include relatives and others.]—directors, officers, or important shareholders—can have a substantial trading advantage if they are privy to important confidential information. Learning bad news (such as financial loss or cancellation of key contracts) in advance of all other stockholders will permit the privileged few to sell shares before the price falls. Conversely, discovering good news (a major oil find or unexpected profits) in advance gives the insider a decided incentive to purchase shares before the price rises.

Because of the unfairness to those who are ignorant of inside information, federal law prohibits insider trading.^[Buying or selling securities of a publicly held company by those who have privileged access to information concerning a company’s financial condition or plans.] Two provisions of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act are paramount: Section 16(b) and 10(b).

Recapture of Short-Swing Profits: Section 16(b)

The Securities Exchange Act assumes that any director, officer, or shareholder owning 10 percent or more of the stock in a corporation is using inside information if he or any family member makes a profit from trading activities, either buying and selling or selling and buying, during a six-month period. Section 16(b) penalizes any such person by permitting the corporation or a shareholder suing on its behalf to recover the short-swing profits. The law applies to any company with more than $10 million in assets and at least five hundred or more shareholders of any class of stock.

Suppose that on January 1, Bob (a company officer) purchases one hundred shares of stock in BCT Bookstore, Inc., for $60 a share. On September 1, he sells them for $100 a share. What is the result? Bob is in the clear, because his $4,000 profit was not realized during a six-month period. Now suppose that the price falls, and one month later, on October 1, he repurchases one hundred shares at $30 a share and holds them for two years. What is the result? He will be forced to pay back $7,000 in profits even if he had no inside information. Why? In August, Bob held one hundred shares of stock, and he did again on October 1—within a six-month period. His net gain on these transactions was $7,000 ($10,000 realized on the sale less the $3,000 cost of the purchase).

As a consequence of Section 16(b) and certain other provisions, trading in securities by directors, officers, and large stockholders presents numerous complexities. For instance, the law requires people in this position to make periodic reports to the SEC about their trades. As a practical matter, directors, officers, and large shareholders should not trade in their own company stock in the short run without legal advice.

Insider Trading: Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5

Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 prohibits any person from using the mails or facilities of interstate commerce “to use or employ, in connection with the purchase or sale of any security…any manipulative or deceptive device or contrivance in contravention of such rules and regulations as the Commission may prescribe as necessary or appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors.” In 1942, the SEC learned of a company president who misrepresented the company’s financial condition in order to buy shares at a low price from current stockholders. So the commission adopted a rule under the authority of Section 10(b). Rule 10b-5A, as it was dubbed, has remained unchanged for more than forty years and has spawned thousands of lawsuits and SEC proceedings. It reads as follows:

It shall be unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, by the use of any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce, or of the mails, or of any facility of any national securities exchange,

(1) to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud,

(2) to make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of circumstances under which they were made, not misleading, or

(3) to engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person, in connection with the purchase or sale of any security.

Rule 10b-5 applies to any person who purchases or sells any security. It is not limited to securities registered under the 1934 Securities Exchange Act. It is not limited to publicly held companies. It applies to any security issued by any company, including the smallest closely held company. In substance, it is an antifraud rule, enforcement of which seems, on its face, to be limited to action by the SEC. But over the years, the courts have permitted people injured by those who violate the statute to file private damage suits. This sweeping rule has at times been referred to as the “federal law of corporations” or the “catch everybody” rule.

Insider trading ran headlong into Rule 10b-5 beginning in 1964 in a series of cases involving Texas Gulf Sulphur Company (TGS). On November 12, 1963, the company discovered a rich deposit of copper and zinc while drilling for oil near Timmins, Ontario. Keeping the discovery quiet, it proceeded to acquire mineral rights in adjacent lands. By April 1964, word began to circulate about TGS’s find.

Newspapers printed rumors, and the Toronto Stock Exchange experienced a wild speculative spree. On April 12, an executive vice president of TGS issued a press release downplaying the discovery, asserting that the rumors greatly exaggerated the find and stating that more drilling would be necessary before coming to any conclusions. Four days later, on April 16, TGS publicly announced that it had uncovered a strike of 25 million tons of ore. In the months following this announcement, TGS stock doubled in value.

The SEC charged several TGS officers and directors with having purchased or told their friends, so-called tippees, to purchase TGS stock from November 12, 1963, through April 16, 1964, on the basis of material inside information. The SEC also alleged that the April 12, 1964, press release was deceptive. The US Court of Appeals, in SEC v. Texas Gulf Sulphur Co.[8] decided that the defendants who purchased the stock before the public announcement had violated Rule 10b-5. According to the court, “anyone in possession of material inside information must either disclose it to the investing public, or, if he is disabled from disclosing to protect a corporate confidence, or he chooses not to do so, must abstain from trading in or recommending the securities concerned while such inside information remains undisclosed.” On remand, the district court ordered certain defendants to pay $148,000 into an escrow account to be used to compensate parties injured by the insider trading.

The court of appeals also concluded that the press release violated Rule 10b-5 if “misleading to the reasonable investor.” On remand, the district court held that TGS failed to exercise “due diligence” in issuing the release. Sixty-nine private damage actions were subsequently filed against TGS by shareholders who claimed they sold their stock in reliance on the release. The company settled most of these suits in late 1971 for $2.7 million.

The Supreme Court has placed limitations on the liability of tippees under Rule 10b-5. In 1980, the Court reversed the conviction of an employee of a company that printed tender offer and merger prospectuses. Using information obtained at work, the employee had purchased stock in target companies and later sold it for a profit when takeover attempts were publicly announced. In Chiarella v. United States, the Court held that the employee was not an insider or a fiduciary and that “a duty to disclose under Section 10(b) does not arise from the mere possession of nonpublic market information.”[9] Following Chiarella, the Court ruled in Dirks v. Securities and Exchange Commission, that tippees are liable if they had reason to believe that the tipper breached a fiduciary duty in disclosing confidential information and the tipper received a personal benefit from the disclosure.

The Supreme Court has broadly interpreted this “personal benefit” requirement. For instance, giving insider information to a family member for intangible relationship benefits can count as receiving a personal benefit, and hence violating a fiduciary duty.

In 2000, the SEC enacted Rule 10b5-1, which defines trading “on the basis of” inside information as any time a person trades while aware of material nonpublic information. Therefore, a defendant is not saved by arguing that the trade was made independent of knowledge of the nonpublic information. However, the rule also creates an affirmative defense for trades that were planned prior to the person’s receiving inside information.

Summary and Exercises

Summary

The hallmark of the corporate form of business enterprise is limited liability for its owners. Other features of corporations are separation of ownership and management, perpetual existence, and easy transferability of interests. The corporation, as a legal entity, has many of the usual rights accorded natural persons. The principle of limited liability is broad but not absolute: when the corporation is used to commit a fraud or an injustice or when the corporation does not act as if it were one, the courts will pierce the corporate veil and pin liability on stockholders.

Besides the usual business corporation, there are other forms, including not-for-profit corporations and professional corporations. Business corporations are classified into two types: publicly held and closely held corporations.

Because ownership and control are separated in the modern publicly held corporation, shareholders generally do not make business decisions. Shareholders who own voting stock do retain the power to elect directors, amend the bylaws, ratify or reject certain corporate actions, and vote on certain extraordinary matters, such as whether to amend the articles of incorporation, merge, or liquidate.

Directors have the ultimate authority to run the corporation and are fiduciaries of the firm. In large corporations, directors delegate day-to-day management to salaried officers, whom they may fire, in most states, without cause. The full board of directors may, by majority, vote to delegate its authority to committees.

Directors owe the company a duty of loyalty and of care. A contract between a director and the company is voidable unless fair to the corporation or unless all details have been disclosed and the disinterested directors or shareholders have approved. Any director or officer is obligated to inform fellow directors of any corporate opportunity that affects the company and may not act personally on it unless he has received approval. Additionally, the business judgment rule may operate to protect the decisions of the board.

The general rule is to maximize shareholder value, but over time, corporations have been permitted to consider other factors in decision making. Constituency statutes, for example, allow the board to consider factors other than maximizing shareholder value. Corporate social responsibility has increased, as firms consider things such as environmental impact and consumer perception in making decisions. Special business forms such as benefit corporations allow even greater flexibility in meeting social responsibility.

Beyond state corporation laws, federal statutes (most importantly, the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934) regulate the issuance and trading of corporate securities. The federal definition of security is broad, encompassing most investments, even those called by other names.

The law does not prohibit risky stock offerings; it bans only those lacking adequate disclosure of risks. The primary means for realizing this goal is the registration requirement: registration statements, prospectuses, and proxy solicitations must be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Penalties for violation of securities law include criminal fines and jail terms, and damages may be awarded in civil suits by both the SEC and private individuals injured by the violation of SEC rules.

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 presents special hazards to those trading in public stock on the basis of inside information. One provision requires the reimbursement to the company of any profits made from selling and buying stock during a six-month period by directors, officers, and shareholders owning 10 percent or more of the company’s stock. Under Rule 10b-5, the SEC and private parties may sue insiders who traded on information not available to the general public, thus gaining an advantage in either selling or buying the stock. Insiders include company employees. People who trade on stock tips in exchange for personal benefit also risk liability.

Exercises

- Eric was hired as a management consultant by a major corporation to conduct a study, which took him three months to complete. While working on the study, Eric learned that someone working in research and development for the company had recently made an important discovery. Before the discovery was announced publicly, Eric purchased stock in the company. Did he violate federal securities law? Why?

- While working for the company, Eric also learned that it was planning a takeover of another corporation. Before announcement of a tender offer, Eric purchased stock in the target company. Did he violate securities law? Why?

- A minority shareholder brought suit against the Chicago Cubs, a Delaware corporation, and their directors on the grounds that the directors were negligent in failing to install lights in Wrigley Field. The shareholder specifically alleged that the majority owner, Philip Wrigley, failed to exercise good faith in that he personally believed that baseball was a daytime sport and felt that night games would cause the surrounding neighborhood to deteriorate. The shareholder accused Wrigley and the other directors of not acting in the best financial interests of the corporation. What counterarguments should the directors assert? Who will win? Why?

- The CEO of First Bank, without prior notice to the board, announced a merger proposal during a two-hour meeting of the directors. Under the proposal, the bank was to be sold to an acquirer at $55 per share. (At the time, the stock traded at $38 per share.) After the CEO discussed the proposal for twenty minutes, with no documentation to support the adequacy of the price, the board voted in favor of the proposal. Although senior management strongly opposed the proposal, it was eventually approved by the stockholders, with 70 percent in favor and 7 percent opposed. A group of stockholders later filed a class action, claiming that the directors were personally liable for the amount by which the fair value of the shares exceeded $55—an amount allegedly in excess of $100 million. Are the directors personally liable? Why or why not?

- While waiting tables at a campus restaurant, you overhear a conversation between two corporate executives who indicate that their company has developed a new product that will revolutionize the computer industry. The product is to be announced in three weeks. If you purchase stock in the company before the announcement, will you be liable under federal securities law? Why?

- Cornell University v. Fiske, 136 U.S. 152 (1890). ↵

- D & O Claims Incidence Rises,” Business Insurance, November 12, 1979, 18. ↵

- Smith v. Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d 858 (Del. 1985). ↵

- Aronson v. Lewis, 473 A.2d 805, 812 (Del. 1984). ↵

- D. I. Felsenthal Co. v. Northern Assurance Co., Ltd., 284 Ill. 343, 120 N.E. 268 (1918). ↵

- Felsenthal Co. v. Northern Assurance Co., Ltd., 120 N.E. 268 (Ill. 1918). ↵

- A failure to follow corporate formalities—for example, inadequate capitalization or commingling of assets—can subject stockholders to personal liability. ↵

- SEC v. Texas Gulf Sulphur Co., 401 F.2d 833 (2d Cir. 1968) ↵

- Chiarella v. United States, 445 U.S. 222 (1980). ↵

A corporation that exists in law, having met all of the necessary legal requirements.

A set of documents that a company must file with the SEC before it proceeds with an initial public offering.

A document that provides details about an investment offering for sale to the public—the facts an investor needs to make an informed decision.

The market in which the money or capital for the security is received by the issuer of the security directly from investors (such as in an initial public offering transaction).

The market in which securities are bought and sold subsequent to original issuance and are typically held by one investor selling them to another investor.

A section of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act that allows shareholders to sue corporate officers, directors, or owners of more than 10% of the company’s shares for any profits made by insider trading. 16(b) is not enforced by the SEC,but by private parties, and covers profits made within a “short swing” (six month) period.

Any profits made from the purchase and sale of company stock if both transactions occur within a six-month period; insiders are required to return any profits made from the purchase and sale of company stock if both transactions occur within a six-month period.

A section of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 that prohibits any person from using the mails or facilities of interstate commerce “to use or employ, in connection with the purchase or sale of any security…any manipulative or deceptive device…”

A rule by the SEC that applies to any person who purchases or sells any security and that prohibits fraud related to securities trading.

Someone who receives and acts on insider information.

A provision that defines when a purchase or sale constitutes trading “on the basis of” material nonpublic information as any time a person trades while aware of material nonpublic information.