16 Secured Transactions and Bankruptcy

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should understand the following:

- The basic concepts of secured transactions

- Creation and perfection of the security interest

- Priorities for claims on the security interest

- Rights of creditors on default

- The basic operation of Chapter 7 bankruptcy

- The basic operation of Chapter 11 bankruptcy

- The basic operation of Chapter 13 bankruptcy

Introduction to Secured Transactions

Creditors want assurances that they will be repaid by the debtor. An oral promise to pay is no security at all, and—as it is oral—it is difficult to prove. A signature loan is merely a written promise by the debtor to repay, but the creditor stuck holding a promissory note with a signature loan only—while he may sue a defaulting debtor—will get nothing if the debtor is insolvent. Again, that’s no security at all. Real security for the creditor comes in two forms: by agreement with the debtor or by operation of law without an agreement.

Security obtained through agreement comes in three major types: (1) personal property security (the most common form of security, which we will cover in this chapter); (2) suretyship—the willingness of a third party to pay if the primarily obligated party does not; and (3) mortgage of real estate.

The law of secured transactions consists of five principal components: (1) the nature of property that can be the subject of a security interest; (2) the methods of creating the security interest; (3) the perfection of the security interest against claims of others; (4) priorities among secured and unsecured creditors—that is, who will be entitled to the secured property if more than one person asserts a legal right to it; and (5) the rights of creditors when the debtor defaults. After considering the source of the law and some key terminology, we examine each of these components in turn.

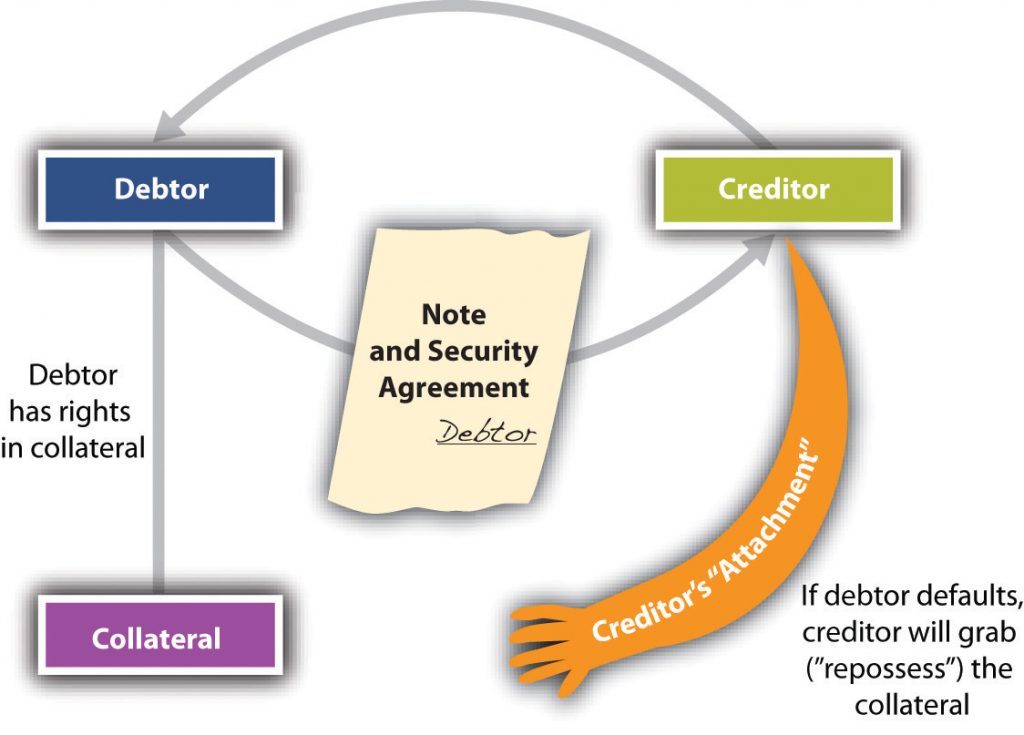

Here is the simplest (and most common) scenario: Debtor borrows money or obtains credit from Creditor, signs a note and security agreement putting up collateral, and promises to pay the debt or, upon Debtor’s default, let Creditor (secured party) take possession of (repossess) the collateral and sell it. “The Grasping Hand” Figure illustrates this scenario—the grasping hand is Creditor’s reach for the collateral, but the hand will not close around the collateral and take it (repossess) unless Debtor defaults.

Source of Law

Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) governs security interests in personal property. The UCC defines the scope of the article (here slightly truncated):[1]

As always, it is necessary to review some definitions so that communication on the topic at hand is possible. The secured transaction always involves a debtor, a secured party, a security agreement, a security interest, and collateral.

Article 9 applies to any transaction “that creates a security interest.” The UCC in Section 1-201(35) defines security interest as “an interest in personal property or fixtures which secures payment or performance of an obligation.”

Security agreement is “an agreement that creates or provides for a security interest.” It is the contract that sets up the debtor’s duties and the creditor’s rights in event the debtor defaults.[2]

Collateral “means the property subject to a security interest or agricultural lien.”[3]

Purchase-money security interest (PMSI) is the simplest form of security interest. Section 9-103(a) of the UCC defines “purchase-money collateral” as “goods or software that secures a purchase-money obligation with respect to that collateral.” A PMSI arises where the debtor gets credit to buy goods and the creditor takes a secured interest in those goods. Suppose you want to buy a big hardbound textbook on credit at your college bookstore. The manager refuses to extend you credit outright but says she will take back a PMSI. In other words, she will retain a security interest in the book itself, and if you don’t pay, you’ll have to return the book; it will be repossessed. Contrast this situation with a counteroffer you might make: because she tells you not to mark up the book (in the event that she has to repossess it if you default), you would rather give her some other collateral to hold—for example, your gold college signet ring. Her security interest in the ring is not a PMSI but a pledge; a PMSI must be an interest in the particular goods purchased. A PMSI would also be created if you borrowed money to buy the book and gave the lender a security interest in the book.

Secured party is “a person in whose favor a security interest is created or provided for under a security agreement,” and it includes people to whom accounts, chattel paper, payment intangibles, or promissory notes have been sold; consignors; and others under Section 9-102(a)(72).

Property Subject to the Security Interest

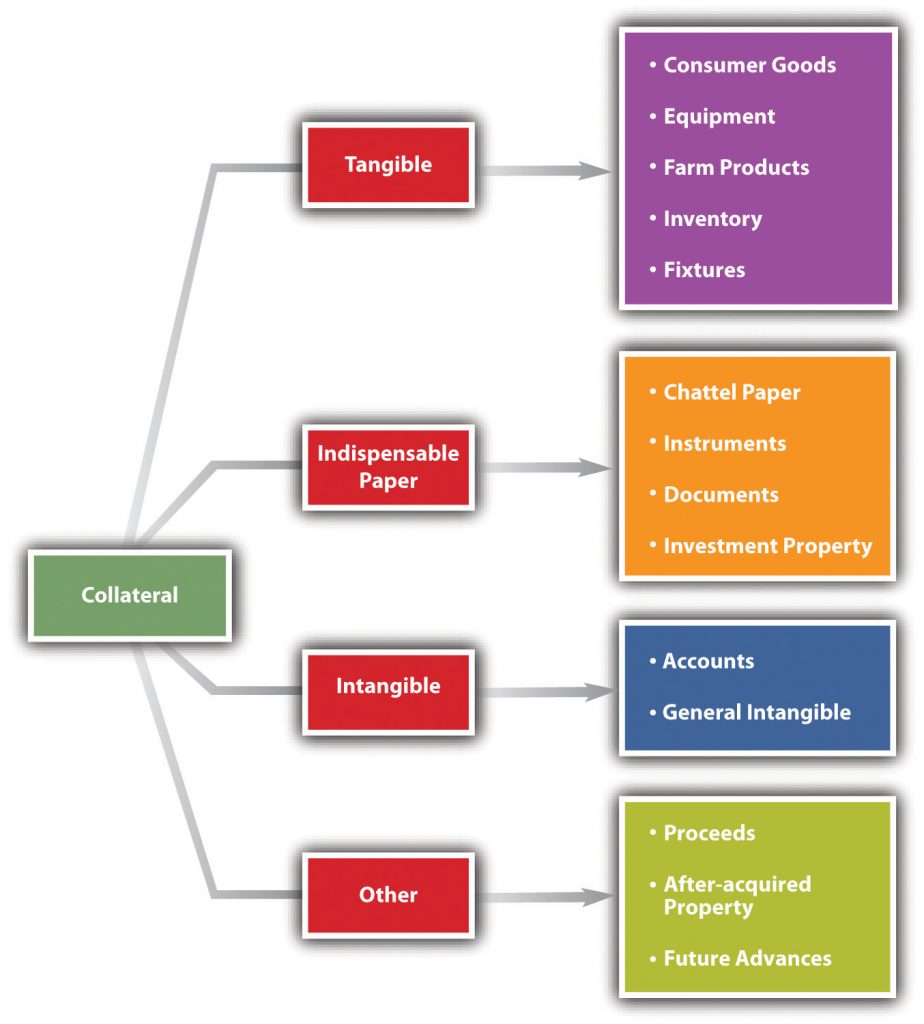

Now we examine what property may be put up as security—collateral. Collateral is—again—property that is subject to the security interest. It can be divided into four broad categories: goods, intangible property, indispensable paper, and other types of collateral. We will consider several in this section.

Goods

Tangible property as collateral is goods. Goods means “all things that are movable when a security interest attaches. The term includes (i) fixtures, (ii) standing timber that is to be cut and removed under a conveyance or contract for sale, (iii) the unborn young of animals, (iv) crops grown, growing, or to be grown, even if the crops are produced on trees, vines, or bushes, and (v) manufactured homes. The term also includes a computer program embedded in goods.”[4] Goods are divided into several subcategories; several are taken up here.

Consumer Goods

These are “goods used or bought primarily for personal, family, or household purposes.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(a)(48).

Inventory

“Goods, other than farm products, held by a person for sale or lease or consisting of raw materials, works in progress, or material consumed in a business.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(a)(48).

Farm Products

“Crops, livestock, or other supplies produced or used in farming operations,” including aquatic goods produced in aquaculture.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(a)(34).

Equipment

This is the residual category, defined as “goods other than inventory, farm products, or consumer goods.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(a)(33).

Accounts

This type of intangible property includes accounts receivable (the right to payment of money), insurance policy proceeds, energy provided or to be provided, winnings in a lottery, health-care-insurance receivables, promissory notes, securities, letters of credit, and interests in business entities.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(a)(2). Often there is something in writing to show the existence of the right—such as a right to receive the proceeds of somebody else’s insurance payout—but the writing is merely evidence of the right. The paper itself doesn’t have to be delivered for the transfer of the right to be effective; that’s done by assignment.

Other Types of Collateral

Among possible other types of collateral that may be used as security is the floating lien.A lien that is expanded to cover any additional property that is acquired by the debtor while the debt is outstanding. This is a security interest in property that was not in the possession of the debtor when the security agreement was executed. The floating lien creates an interest that floats on the river of present and future collateral and proceeds held by—most often—the business debtor. It is especially useful in loans to businesses that sell their collateralized inventory. Without the floating lien, the lender would find its collateral steadily depleted as the borrowing business sells its products to its customers. Pretty soon, there’d be no security at all. The floating lien includes the following:

- After-acquired property. This is property that the debtor acquires after the original deal was set up. It allows the secured party to enhance his security as the debtor (obligor) acquires more property subject to collateralization.

- Sale proceeds. These are proceeds from the disposition of the collateral. Carl Creditor takes a secured interest in Deborah Debtor’s sailboat. She sells the boat and buys a garden tractor. The secured interest attaches to the garden tractor.

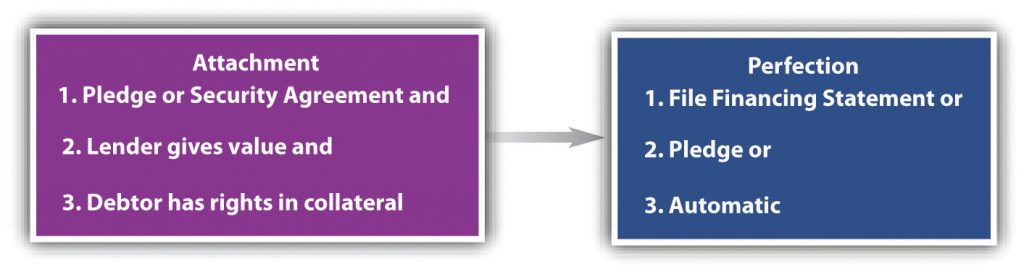

Attachment of a Security Interest

Attachment is the term used to describe when a security interest becomes enforceable against the debtor with respect to the collateral. In the “The Grasping Hand” figure above, ”Attachment” is the outreached hand that is prepared, if the debtor defaults, to grasp the collateral.

There are three requirements for attachment: (1) the secured party gives value; (2) the debtor has rights in the collateral or the power to transfer rights in it to the secured party; (3) the parties have a security agreement “authenticated” (signed) by the debtor, or the creditor has possession of the collateral.

The creditor, or secured party, must give “value” for the security interest to attach. Typically this is extending credit to the debtor. The debtor must have rights in the collateral. Most commonly, the debtor owns the collateral (or has some ownership interest in it). The rights need not necessarily be the immediate right to possession, but they must be rights that can be conveyed.[5] A person can’t put up as collateral property she doesn’t own.

The debtor most often signs the written security agreement, or contract. The UCC says that “the debtor [must have] authenticated a security agreement that provides a description of the collateral.…” “Authenticating” (or “signing,” “adopting,” or “accepting”) means to sign or, in recognition of electronic commercial transactions, “to execute or otherwise adopt a symbol, or encrypt or similarly process a record…with the present intent of the authenticating person to identify the person and adopt or accept a record.” The “record” is the modern UCC’s substitution for the term “writing.” It includes information electronically stored or on paper. The “authenticating record” (the signed security agreement) is not required in some cases. It is not required if the debtor makes a pledge of the collateral—that is, delivers it to the creditor for the creditor to possess.

Perfection of a Security Interest

As between the debtor and the creditor, attachment is fine: if the debtor defaults, the creditor will repossess the goods and—usually—sell them to satisfy the outstanding obligation. But unless an additional set of steps is taken, the rights of the secured party might be subordinated to the rights of other secured parties, certain lien creditors, bankruptcy trustees, and buyers who give value and who do not know of the security interest. Perfection is the secured party’s way of announcing the security interest to the rest of the world. It is the secured party’s claim on the collateral.

There are five ways a creditor may perfect a security interest: (1) by filing a financing statement, (2) by taking or retaining possession of the collateral, (3) by taking control of the collateral, (4) by taking control temporarily as specified by the UCC, or (5) by taking control automatically.

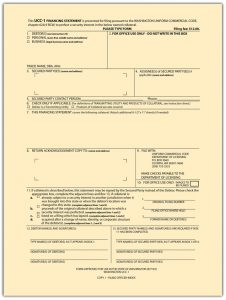

“Except as otherwise provided…a financing statement must be filed to perfect all security agreements.”[6]A financing statement is a simple notice showing the creditor’s general interest in the collateral. It is what’s filed to establish the creditor’s “dibs.”

It may consist of the security agreement itself, as long as it contains the information required by the UCC, but most commonly it is much less detailed than the security agreement: it “indicates merely that a person may have a security interest in the collateral[.]…Further inquiry from the parties concerned will be necessary to disclose the full state of affairs.”[7] The financing statement must provide the following information:

- The debtor’s name. Financing statements are indexed under the debtor’s name, so getting that correct is important. Section 9-503 of the UCC describes what is meant by “name of debtor.”

- The secured party’s name.

- An “indication” of what collateral is covered by the financing statement.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-502(a). It may describe the collateral or it may “indicate that the financing statement covers all assets or all personal property” (such generic references are not acceptable in the security agreement but are OK in the financing statement).[8] If the collateral is real-property-related, covering timber to be cut or fixtures, it must include a description of the real property to which the collateral is related.

The form of the financing statement may vary from state to state, but see the “UCC-1 Financing Statement” Figure for a typical financing statement. Minor errors or omissions on the form will not make it ineffective, but the debtor’s signature is required unless the creditor is authorized by the debtor to make the filing without a signature, which facilitates paperless filing.

Generally, the financing statement is effective for five years; a continuation statement may be filed within six months before the five-year expiration date, and it is good for another five years. The UCC also has rules for continued perfection of security interests when the debtor—whether an individual or an association (corporation)—moves from one state to another. Generally, an interest remains perfected until the earlier of when the perfection would have expired or for four months after the debtor moves to a new jurisdiction. For most real-estate-related filings—ore to be extracted from mines, agricultural collateral, and fixtures—the place to file is with the local office that files mortgages, typically the county auditor’s office.[9] For other collateral, the filing place is as duly authorized by the state. In some states, that is the office of the Secretary of State; in others, it is the Department of Licensing; or it might be a private party that maintains the state’s filing system.[10] The filing should be made in the state where the debtor has his or her primary residence for individuals, and in the state where the debtor is organized if it is a registered organization.[11] The point is, creditors need to know where to look to see if the collateral offered up is already encumbered. In any event, filing the statement in more than one place can’t hurt. The filing office will provide instructions on how to file; these are available online, and electronic filing is usually available for at least some types of collateral.

Exemptions

Some transactions are exempt from the filing provision. The most important category of exempt collateral is that covered by state certificate of title laws. For example, many states require automobile owners to obtain a certificate of title from the state motor vehicle office. Most of these states provide that it is not necessary to file a financing statement in order to perfect a security interest in an automobile. The reason is that the motor vehicle regulations require any security interests to be stated on the title, so that anyone attempting to buy a car in which a security interest had been created would be on notice when he took the actual title certificate.[12]

Temporary Perfection

The UCC provides that certain types of collateral are automatically perfected but only for a while: “A security interest in certificated securities, or negotiable documents, or instruments is perfected without filing or the taking of possession for a period of twenty days from the time it attaches to the extent that it arises for new value given under an authenticated security agreement.”[13] Similar temporary perfection covers negotiable documents or goods in possession of a bailee, and when a security certificate or instrument is delivered to the debtor for sale, exchange, presentation, collection, enforcement, renewal, or registration.[14]After the twenty-day period, perfection would have to be by one of the other methods mentioned here.

Perfection by Possession

A secured party may perfect the security interest by possession where the collateral is negotiable documents, goods, instruments, money, tangible chattel paper, or certified securities.[15] This is a pledge of assets (mentioned in the example of the stamp collection). No security agreement is required for perfection by possession.

Automatic Perfection

The fifth mechanism of perfection is addressed in Section 9-309 of the UCC: there are several circumstances where a security interest is perfected upon mere attachment. The most important here is automatic perfection of a purchase-money security interest given in consumer goods. If a seller of consumer goods takes a PMSI in the goods sold, then perfection of the security interest is automatic. But the seller may file a financial statement and faces a risk if he fails to file and the consumer debtor sells the goods. Under Section 9-320(b), a buyer of consumer goods takes free of a security interest, even though perfected, if he buys without knowledge of the interest, pays value, and uses the goods for his personal, family, or household purposes—unless the secured party had first filed a financing statement covering the goods.

Priorities

Priorities: this is the money question.[16] Who gets what when a debtor defaults? Depending on how the priorities in the collateral were established, even a secured creditor may walk away with the collateral or with nothing. Here we take up the general rule and the exceptions.

Generally, the first to perfect gets first claim on the collateral, and then the first to attach among unperfected parties. If both parties have perfected, the first to perfect wins. If one has perfected and one attached, the perfected party wins. If both have attached without perfection, the first to attach wins. If neither has attached, they are unsecured creditors. Let’s test this general rule against the following situations:

- Rosemary, without having yet lent money, files a financing statement on February 1 covering certain collateral owned by Susan—Susan’s fur coat. Under UCC Article 9, a filing may be made before the security interest attaches. On March 1, Erika files a similar statement, also without having lent any money. On April 1, Erika loans Susan $1,000, the loan being secured by the fur coat described in the statement she filed on March 1. On May 1, Rosemary also loans Susan $1,000, with the same fur coat as security. Who has priority? Rosemary does, since she filed first, even though Erika actually first extended the loan, which was perfected when made (because she had already filed). This result is dictated by the rule even though Rosemary may have known of Erika’s interest when she subsequently made her loan.

- Susan cajoles both Rosemary and Erika, each unknown to the other, to loan her $1,000 secured by the fur coat, which she already owns and which hangs in her coat closet. Erika gives Susan the money a week after Rosemary, but Rosemary has not perfected and Erika does not either. A week later, they find out they have each made a loan against the same coat. Who has priority? Whoever perfects first: the rule creates a race to the filing office or to Susan’s closet. Whoever can submit the financing statement or actually take possession of the coat first will have priority, and the outcome does not depend on knowledge or lack of knowledge that someone else is claiming a security interest in the same collateral. But what of the rule that in the absence of perfection, whichever security interest first attached has priority? This is “thought to be of merely theoretical interest,” says the UCC commentary, “since it is hard to imagine a situation where the case would come into litigation without [either party] having perfected his interest.” And if the debtor filed a petition in bankruptcy, neither unperfected security interest could prevail against the bankruptcy trustee.

To rephrase: An attached security interest prevails over other unsecured creditors (unsecured creditors lose to secured creditors, perfected or unperfected). If both parties are secured (have attached the interest), the first to perfect wins.[17] If both parties have perfected, the first to have perfected wins.[18]

Exemptions

The UCC provides that “a perfected purchase-money security interest in goods other than inventory or livestock has priority over a conflicting security interest in the same goods…if the purchase-money security interest is perfected when debtor receives possession of the collateral or within 20 days thereafter.”[19]The Official Comment to this UCC section observes that “in most cases, priority will be over a security interest asserted under an after-acquired property clause.”

Suppose Susan manufactures fur coats. On February 1, Rosemary advances her $10,000 under a security agreement covering all Susan’s machinery and containing an after-acquired property clause. Rosemary files a financing statement that same day. On March 1, Susan buys a new machine from Erika for $5,000 and gives her a security interest in the machine; Erika files a financing statement within twenty days of the time that the machine is delivered to Susan. Who has priority if Susan defaults on her loan payments? Under the PMSI rule, Erika has priority, because she had a PMSI. Suppose, however, that Susan had not bought the machine from Erika but had merely given her a security interest in it. Then Rosemary would have priority, because her filing was prior to Erika’s.

What would happen if this kind of PMSI in noninventory goods (here, equipment) did not get priority status? A prudent Erika would not extend credit to Susan at all, and if the new machine is necessary for Susan’s business, she would soon be out of business. That certainly would not inure to the benefit of Rosemary. It is, mostly, to Rosemary’s advantage that Susan gets the machine: it enhances Susan’s ability to make money to pay Rosemary.

The UCC also provides that a perfected PMSI in inventory has priority over conflicting interests in the same inventory, provided that the PMSI is perfected when the debtor receives possession of the inventory, the PMSI-secured party sends an authenticated notification to the holder of the conflicting interest and that person receives the notice within five years before the debtor receives possession of the inventory, and the notice states that the person sending it has or expects to acquire a PMSI in the inventory and describes the inventory.[20] The notice requirement is aimed at protecting a secured party in the typical situation in which incoming inventory is subject to a prior agreement to make advances against it. If the original creditor gets notice that new inventory is subject to a PMSI, he will be forewarned against making an advance on it; if he does not receive notice, he will have priority. It is usually to the earlier creditor’s advantage that her debtor is able to get credit to “floor” (provide) inventory, without selling which, of course, the debtor cannot pay back the earlier creditor.

Now we look at buyers who take priority over perfected security interests. Sometimes people who buy things even covered by a perfected security interest win out (the perfected secured party loses). “A buyer in the ordinary course of business, other than [one buying farm products from somebody engaged in farming] takes free of a security interest created by the buyer’s seller, even if the security interest is perfected and the buyer knows [it].”[21]

Rights of Creditor on Default and Disposition after Repossession

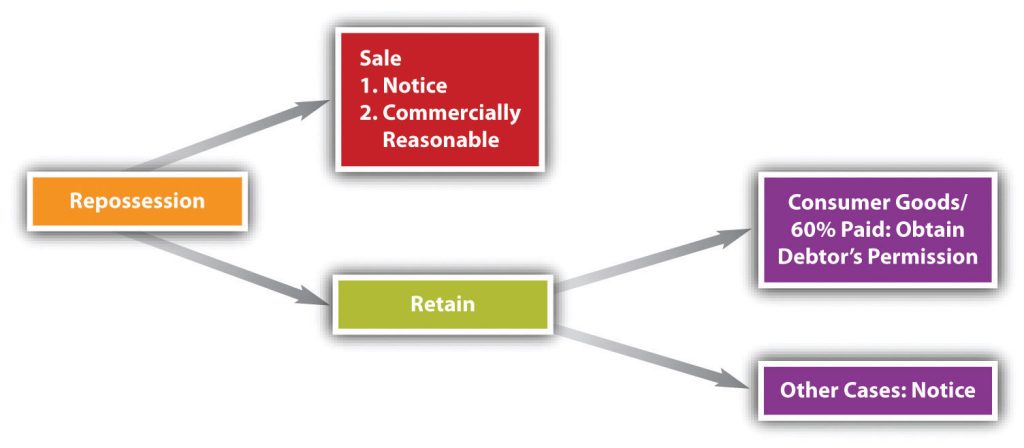

Upon default, the creditor must make an election: to sue, or to repossess.

Resort to Judicial Process

After a debtor’s default (e.g., by missing payments on the debt), the creditor could ignore the security interest and bring suit on the underlying debt. But creditors rarely resort to this remedy because it is time-consuming and costly. Most creditors prefer to repossess the collateral and sell it or retain possession in satisfaction of the debt.

Repossession

Section 9-609 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) permits the secured party to take possession of the collateral on default (unless the agreement specifies otherwise):

(a) After default, a secured party may (1) take possession of the collateral; and (2) without removal, may render equipment unusable and dispose of collateral on a debtor’s premises.

(b) A secured party may proceed under subsection (a): (1) pursuant to judicial process; or (2) without judicial process, if it proceeds without breach of the peace.

This language has given rise to the flourishing business of professional “repo men” (and women). “Repo” companies are firms that specialize in repossession collateral. They have trained car-lock pickers, in-house locksmiths, experienced repossession teams, damage-free towing equipment, and the capacity to deliver repossessed collateral to the client’s desired destination. Some firms advertise that they have 360-degree video cameras that record every aspect of the repossession. They have “skip chasers”—people whose business it is to track down those who skip out on their obligations, and they are trained not to breach the peace.

The creditor’s agents—the repo people—charge for their service, of course, and if possible the cost of repossession comes out of the collateral when it’s sold. A debtor would be better off voluntarily delivering the collateral according to the creditor’s instructions, but if that doesn’t happen, “self-help”—repossession—is allowed because, of course, the debtor said it would be allowed in the security agreement, so long as the repossession can be accomplished without breach of peace. “Breach of peace” is language that can cover a wide variety of situations over which courts do not always agree. For example, some courts interpret a creditor’s taking of the collateral despite the debtor’s clear oral protest as a breach of the peace; other courts do not.

Disposition after Repossession

After repossession, the creditor has two options: sell the collateral or accept it in satisfaction of the debt. Sale is the usual method of recovering the debt. Section 9-610 of the UCC permits the secured creditor to “sell, lease, license, or otherwise dispose of any or all of the collateral in its present condition or following any commercially reasonable preparation or processing.” The collateral may be sold as a whole or in parcels, at one time or at different times. Two requirements limit the creditor’s power to resell: (1) it must send notice to the debtor and secondary obligor, and (unless consumer goods are sold) to other secured parties; and (2) all aspects of the sale must be “commercially reasonable.”

After repossession, the creditor has two options: sell the collateral or accept it in satisfaction of the debt. Sale is the usual method of recovering the debt. Section 9-610 of the UCC permits the secured creditor to “sell, lease, license, or otherwise dispose of any or all of the collateral in its present condition or following any commercially reasonable preparation or processing.” The collateral may be sold as a whole or in parcels, at one time or at different times. Two requirements limit the creditor’s power to resell: (1) it must send notice to the debtor and secondary obligor, and (unless consumer goods are sold) to other secured parties; and (2) all aspects of the sale must be “commercially reasonable.”

Section 9-615 of the UCC describes how the proceeds are applied: first, to the costs of the repossession, including reasonable attorney’s fees and legal expenses as provided for in the security agreement (and it will provide for that!); second, to the satisfaction of the obligation owed; and third, to junior creditors. This again emphasizes the importance of promptly perfecting the security interest: failure to do so frequently subordinates the tardy creditor’s interest to junior status. If there is money left over from disposing of the collateral—a surplus—the debtor gets that back. If there is still money owing—a deficiency—the debtor is liable for that. In Section 9-616, the UCC carefully explains how the surplus or deficiency is calculated; the explanation is required in a consumer goods transaction, and it has to be sent to the debtor after the disposition.

Because resale can be a bother (or the collateral is appreciating in value), the secured creditor may wish simply to accept the collateral in full satisfaction or partial satisfaction of the debt, as permitted in UCC Section 9-620(a). This is known as strict foreclosure. The debtor must consent to letting the creditor take the collateral without a sale in a “record authenticated after default,” or after default the creditor can send the debtor a proposal for the creditor to accept the collateral, and the proposal is effective if not objected to within twenty days after it’s sent.

The strict foreclosure provisions contain a safety feature for consumer goods debtors. If the debtor has paid at least 60 percent of the debt, then the creditor may not use strict foreclosure—unless the debtor signs a statement after default renouncing his right to bar strict foreclosure and to force a sale.

Introduction to Bankruptcy and Chapter 7 Liquidation

History of Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy law governs the rights of creditors and insolvent debtors who cannot pay their debts. In broadest terms, bankruptcy deals with the seizure of the debtor’s assets and their distribution to the debtor’s various creditors. The term derives from the Renaissance custom of Italian traders, who did their trading from benches in town marketplaces. Creditors literally “broke the bench” of a merchant who failed to pay his debts. The term banco rotta (broken bench) thus came to apply to business failures.

In the Victorian era, many people in both England and the United States viewed someone who became bankrupt as a wicked person. In part, this attitude was prompted by the law itself, which to a greater degree in England and to a lesser degree in the United States treated the insolvent debtor as a sort of felon. Until the second half of the nineteenth century, British insolvents could be imprisoned; jail for insolvent debtors was abolished earlier in the United States. And the entire administration of bankruptcy law favored the creditor, who could with a mere filing throw the financial affairs of the alleged insolvent into complete disarray.

Today a different attitude prevails. Bankruptcy is understood as an aspect of financing, a system that permits creditors to receive an equitable distribution of the bankrupt person’s assets and promises new hope to debtors facing impossible financial burdens. Without such a law, we may reasonably suppose that the level of economic activity would be far less than it is, for few would be willing to risk being personally burdened forever by crushing debt. Bankruptcy gives the honest debtor a fresh start and resolves disputes among creditors.

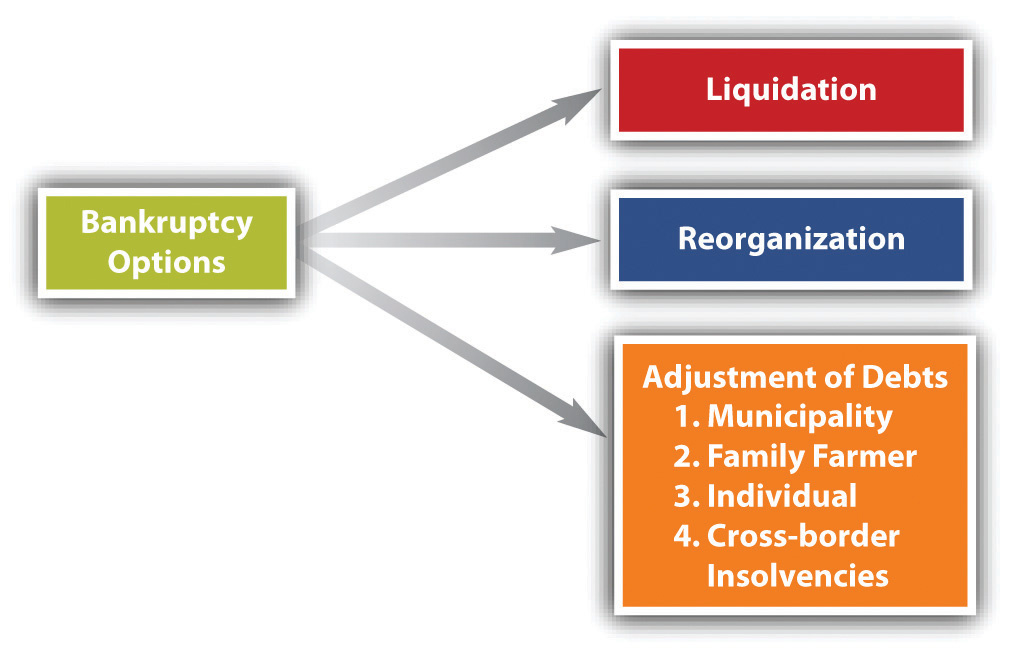

The BAPCPA provides for six different kinds of bankruptcy proceedings. Each is covered by its own chapter in the act and is usually referred to by its chapter number. We will consider only three.

- Chapter 7, Liquidation: applies to all debtors except railroads, insurance companies, most banks and credit unions, and homestead associations.11 United States Code, Section 109(b). A liquidation is a “straight” bankruptcy proceeding. It entails selling the debtor’s nonexempt assets for cash and distributing the cash to the creditors, thereby discharging the insolvent person or business from any further liability for the debt. About 70 percent of all bankruptcy filings are Chapter 7.

- Chapter 11, Reorganization: applies to anybody who could file Chapter 7, plus railroads. It is the means by which a financially troubled company can continue to operate while its financial affairs are put on a sounder basis. A business might liquidate following reorganization but will probably take on new life after negotiations with creditors on how the old debt is to be paid off. A company may voluntarily decide to seek Chapter 11 protection in court, or it may be forced involuntarily into a Chapter 11 proceeding.

- Chapter 13, Adjustment of debts of an individual with regular income: applies only to individuals (no corporations or partnerships) with debt not exceeding about $1.3 million.11 United States Code, Section 109(e). This chapter permits an individual with regular income to establish a repayment plan, usually either a composition (an agreement among creditors) or an extension (a stretch-out of the time for paying the entire debt).

Chapter 7

The basic idea in Chapter 7 is to sell the debtor’s non-exempt assets (so they, e.g., may retain their home), pay off the creditors in a sensible priority order (e.g., secured creditors first), and then to discharge the remaining debts. There are some details.

Recall that the purpose of liquidation is to convert the debtor’s assets—except those exempt under the law—into cash for distribution to the creditors and thereafter to discharge the debtor from further liability. With certain exceptions, any person may voluntarily file a petition to liquidate under Chapter 7. A “person” is defined as any individual, partnership, or corporation. The exceptions are railroads and insurance companies, banks, savings and loan associations, credit unions, and the like.

For a Chapter 7 liquidation proceeding, as for bankruptcy proceedings in general, the various aspects of case administration are covered by the bankruptcy code’s Chapter 3. These include the rules governing commencement of the proceedings, the effect of the petition in bankruptcy, the first meeting of the creditors, and the duties and powers of trustees.

The bankruptcy begins with the filing of a petition in bankruptcy with the bankruptcy court.

Voluntary and Involuntary Petitions

The individual, partnership, or corporation may file a voluntary petition in bankruptcy; 99 percent of bankruptcies are voluntary petitions filed by the debtor. But involuntary bankruptcy is possible, too, under Chapter 7 or Chapter 11. To put anyone into bankruptcy involuntarily, the petitioning creditors must meet three conditions: (1) they must have claims for unsecured debt amounting to at least a statutory amount (around $16,000 as of this writing); (2) three creditors must join in the petition whenever twelve or more creditors have claims against the particular debtor—otherwise, one creditor may file an involuntary petition, as long as his claim is for at least a statutory amount; (3) there must be no bona fide dispute about the debt owing. If there is a dispute, the debtor can resist the involuntary filing, and if she wins the dispute, the creditors who pushed for the involuntary petition have to pay the associated costs. Persons owing less than the statutory amount, farmers, and charitable organizations cannot be forced into bankruptcy.

The Automatic Stay

The petition—voluntary or otherwise—operates as a stay. Upon filing the bankruptcy, an automatic injunction that halts actions by creditors to collect debts. against suits or other actions against the debtor to recover claims, enforce judgments, or create liens (but not alimony collection). In other words, once the petition is filed, the debtor is freed from worry over other proceedings affecting her finances or property. No more debt collection calls! Anyone with a claim, secured or unsecured, must seek relief in the bankruptcy court. This provision in the act can have dramatic consequences. Beset by tens of thousands of products-liability suits for damages caused by asbestos, UNR Industries and Manville Corporation, the nation’s largest asbestos producers, filed (separate) voluntary bankruptcy petitions in 1982; those filings automatically stayed all pending lawsuits.

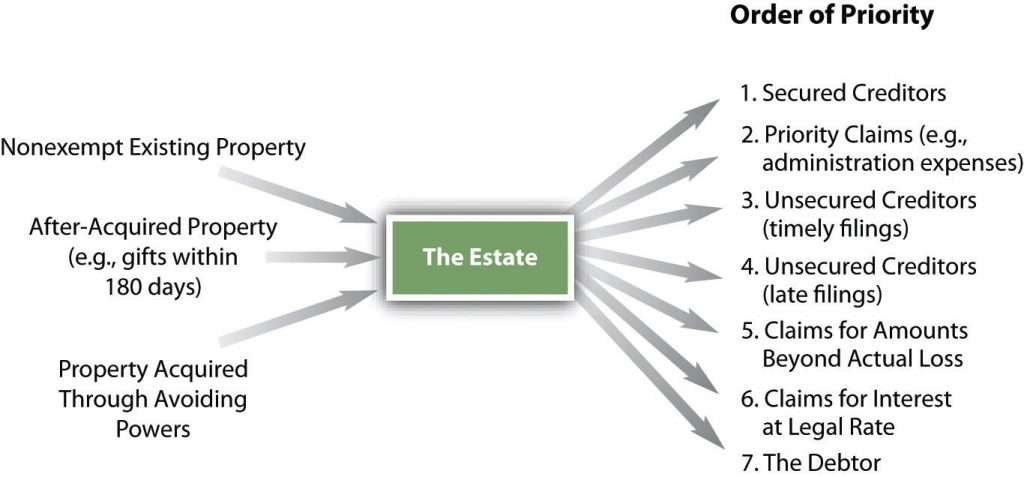

Property Included in the Estate

When a bankruptcy petition is filed, a debtor’s estate is created consisting of all the debtor’s then-existing property interests, whether legal or equitable. In addition, the estate includes any bequests, inheritances, and certain other distributions of property that the debtor receives within the next 180 days. It also includes property recovered by the trustee under certain powers granted by the law. What is not exempt pro debtor’s estateperty will be distributed to the creditors.

Trustee’s Powers and Duties

The act empowers the trustee to use, sell, or lease the debtor’s property in the ordinary course of business or, after notice and a hearing, even if not in the ordinary course of business. In all cases, the trustee must protect any security interests in the property. As long as the court has authorized the debtor’s business to continue, the trustee may also obtain credit in the ordinary course of business. She may invest money in the estate to yield the maximum, but reasonably safe, return. Subject to the court’s approval, she may employ various professionals, such as attorneys, accountants, and appraisers, and may, with some exceptions, assume or reject executory contracts and unexpired leases that the debtor has made. The trustee also has the power to avoid many prebankruptcy transactions in order to recover property of the debtor to be included in the liquidation.

Another power is to avoid transactions known as voidable preferences—transactions highly favorable to particular creditors.[22] A transfer of property is voidable if it was made (1) to a creditor or for his benefit, (2) on account of a debt owed before the transfer was made, (3) while the debtor was insolvent, (4) on or within ninety days before the filing of the petition, and (5) to enable a creditor to receive more than he would have under Chapter 7. If the creditor was an “insider”—one who had a special relationship with the debtor, such as a relative or general partner of the debtor or a corporation that the debtor controls or serves in as director or officer—then the trustee may void the transaction if it was made within one year of the filing of the petition, assuming that the debtor was insolvent at the time the transaction was made.

A third power of the trustee is to avoid fraudulent transfers made within two years before the date that the bankruptcy petition was filed. This provision contemplates various types of fraud. For example, while insolvent, the debtor might transfer property to a relative for less than it was worth, intending to recover it after discharge. This situation should be distinguished from the voidable preference just discussed, in which the debtor pays a favored creditor what he actually owes but in so doing cannot then pay other creditors.

In addition to the duties already noted, the trustee has other duties under Chapter 7. He must sell the property for money, close up the estate “as expeditiously as is compatible with the best interests of parties in interest,” investigate the debtor’s financial affairs, examine proofs of claims, reject improper ones, oppose the discharge of the debtor where doing so is advisable in the trustee’s opinion, furnish a creditor with information about the estate and his administration (unless the court orders otherwise), file tax reports if the business continues to be operated, and make a final report and file it with the court.

Claims with Priority

The bankruptcy act sets out categories of claimants and establishes priorities among them. The law is complex because it sets up different orders of priorities.

First, secured creditors get their security interests before anyone else is satisfied, because the security interest is not part of the property that the trustee is entitled to bring into the estate. This is why being a secured creditor is important, as discussed earlier in this chapter. To the extent that secured creditors have claims in excess of their collateral, they are considered unsecured or general creditors and are lumped in with general creditors of the appropriate class.

Second, of the six classes of claimants, the first is known as that of “priority claims.” It is subdivided into ten categories ranked in order of priority. The highest-priority class within the general class of priority claims must be paid off in full before the next class can share in a distribution from the estate, and so on. Within each class, members will share pro rata if there are not enough assets to satisfy everyone fully. The priority classes, from highest to lowest, are set out in the bankruptcy code (11 USC Section 507) as follows (in part):

- Domestic support obligations (“DSO”), which are claims for support due to the spouse, former spouse, child, or child’s representative, and at a lower priority within this class are any claims by a governmental unit that has rendered support assistance to the debtor’s family obligations.

- Administrative expenses that are required to administer the bankruptcy case itself. Since trustees are paid from the bankruptcy estate, the courts have allowed de facto top priority for administrative expenses because no trustee is going to administer a bankruptcy case for nothing (and no lawyer will work for long without getting paid, either).

- Gap creditors. Claims made by gap creditors in an involuntary bankruptcy petition under Chapter 7 or Chapter 11 are those that arise between the filing of an involuntary bankruptcy petition and the order for relief issued by the court. These claims are given priority because otherwise creditors would not deal with the debtor, usually a business, when the business has declared bankruptcy but no trustee has been appointed and no order of relief issued.

- Employee wages up to a statutory amount for each worker, for the 180 days previous to either the bankruptcy filing or when the business ceased operations, whichever is earlier (180-day period).

- Unpaid contributions to employee benefit plans during the 180-day period, but limited by what was already paid by the employer under subsection (4) above plus what was paid on behalf of the employees by the bankruptcy estate for any employment benefit plan.

- Consumer deposits

- Taxes owed to federal, state, and local governments

- Claims for death or personal injury based on DUI’s

Debtor’s Exemptions

The bankruptcy act exempts certain property of the estate of an individual debtor so that he or she will not be impoverished upon discharge. Exactly what is exempt depends on state law.

Notwithstanding the Constitution’s mandate that Congress establish “uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies,” bankruptcy law is in fact not uniform because the states persuaded Congress to allow nonuniform exemptions. The concept makes sense: what is necessary for a debtor in Maine to live a nonimpoverished postbankruptcy life might not be the same as what is necessary in southern California. These typically include some value in a homestead, some value in a motor vehicle, a certain value of household goods, burial plots, pensions, tools of one’s trade, and so on.

Dischargeable debts

Once discharged, the debtor is no longer legally liable to pay any remaining unpaid debts (except nondischargeable debts) that arose before the court issued the order of relief. The discharge operates to void any money judgments already rendered against the debtor and to bar the judgment creditor from seeking to recover the judgment.

Some debts are not dischargeable in bankruptcy. A bankruptcy discharge varies, depending on the type of bankruptcy the debtor files (Chapter 7, 11, 12, or 13). The most common nondischargeable debts listed in Section 523 include the following:

- All debts not listed in the bankruptcy petition

- Student loans—unless it would be an undue hardship to repay them

- Taxes—federal, state, and municipal

- Fines for violating the law, including criminal fines and traffic tickets

- Alimony and child support, divorce, and other property settlements

- Debts for personal injury caused by driving, boating, or operating an aircraft while intoxicated

- Consumer debts owed to a single creditor and aggregating more than $550 for luxury goods or services incurred within ninety days before the order of relief

- Debts incurred because of fraud or securities law violations

- Debts for willful injury to another’s person or his or her property

- Debts from embezzlement

Chapter 11 and Chapter 13 Bankruptcies

Chapter 11

Chapter 11 provides a means by which corporations, partnerships, and other businesses, including sole proprietorships, can rehabilitate themselves and continue to operate free from the burden of debts that they cannot pay.

Any person eligible for discharge in Chapter 7 proceeding (plus railroads) is eligible for a Chapter 11 proceeding, except stockbrokers and commodity brokers. Individuals filing Chapter 11 must take credit counseling; businesses do not. A company may voluntarily enter Chapter 11 or may be put there involuntarily by creditors. Individuals can file Chapter 11 particularly if they have too much debt to qualify for Chapter 13 and make too much money to qualify for Chapter 7; under the 2005 act, individuals must commit future wages to creditors, just as in Chapter 13.

Unless a trustee is appointed, the debtor will retain possession of the business and may continue to operate with its own management. The court may appoint a trustee on request of any party in interest after notice and a hearing. The appointment may be made for cause—such as dishonesty, incompetence, or gross mismanagement—or if it is otherwise in the best interests of the creditors. Frequently, the same incompetent management that got the business into bankruptcy is left running it—that’s a criticism of Chapter 11.

The court must appoint a committee of unsecured creditors as soon as practicable after issuing the order for relief. The committee must consist of creditors willing to serve who have the seven largest claims, unless the court decides to continue a committee formed before the filing, if the committee was fairly chosen and adequately represents the various claims. The committee has several duties, including these: (1) to investigate the debtor’s financial affairs, (2) to determine whether to seek appointment of a trustee or to let the business continue to operate, and (3) to consult with the debtor or trustee throughout the case.

The Reorganization Plan

The debtor may always file its own plan, whether in a voluntary or involuntary case. If the court leaves the debtor in possession without appointing a trustee, the debtor has the exclusive right to file a reorganization plan during the first 120 days. If it does file, it will then have another 60 days to obtain the creditors’ acceptances. Although its exclusivity expires at the end of 180 days, the court may lengthen or shorten the period for good cause. At the end of the exclusive period, the creditors’ committee, a single creditor, or a holder of equity in the debtor’s property may file a plan. If the court does appoint a trustee, any party in interest may file a plan at any time.

The Bankruptcy Reform Act specifies certain features of the plan and permits others to be included. Among other things, the plan must (1) designate classes of claims and ownership interests; (2) specify which classes or interests are impaired—a claim or ownership interest is impaired if the creditor’s legal, equitable, contractual rights are altered under the plan; (3) specify the treatment of any class of claims or interests that is impaired under the plan; (4) provide the same treatment of each claim or interests of a particular class, unless the holder of a particular claim or interest agrees to a less favorable treatment; and (5) provide adequate means for carrying out the plan. Basically, what the plan does is provide a process for rehabilitating the company’s faltering business by relieving it from repaying part of its debt and initiating reforms so that the company can try to get back on its feet.

The debtor gets discharged when all payments under the plan are completed. A Chapter 11 bankruptcy may be converted to Chapter 7, with some restrictions, if it turns out the debtor cannot make the plan work.

Chapter 13

Anyone with a steady income who is having difficulty paying off accumulated debts may seek the protection of a bankruptcy court in Chapter 13 proceeding (often called the wage earner’s plan). Under this chapter, the individual debtor presents a payment plan to creditors, and the court appoints a trustee. If the creditors wind up with more under the plan presented than they would receive in Chapter 7 proceeding, then the court is likely to approve it. In general, a Chapter 13 repayment plan extends the time to pay the debt and may reduce it so that the debtor need not pay it all. Typically, the debtor will pay a fixed sum monthly to the trustee, who will distribute it to the creditors.

People seek Chapter 13 discharges instead of Chapter 7 for various reasons: they make too much money to pass the Chapter 7 means test; they are behind on their mortgage or car payments and want to make them up over time and reinstate the original agreement; they have debts that can’t be discharged in Chapter 7; they have nonexempt property they want to keep; they have codebtors on a personal debt who would be liable if the debtor went Chapter 7; they have a real desire to pay their debts but cannot do so without getting the creditors to give them some breathing room. Chapter 7 cases may always be converted to Chapter 13.

Plans are typically extensions or compositions—that is, they extend the time to pay what is owing, or they are agreements among creditors each to accept something less than the full amount owed (so that all get something). Under Chapter 13, the stretch-out period is three to five three years. The plan must provide for payments of all future income or a sufficient portion of it to the trustee. Priority creditors are entitled to be paid in full, although they may be paid later than required under the original indebtedness. As long as the plan is being carried out, the debtor may enjoin any creditors from suing to collect the original debt.

Once a debtor has made all payments called for in the plan, the court will discharge him from all remaining debts except certain long-term debts and obligations to pay alimony, maintenance, and support.

A debtor with sufficient income (calculated by a test beyond our scope) who files for Chapter 7 bankruptcy may have their proceedings converted to Chapter 13, which would enable them to pay their creditors additional sums.

Summary and Exercises

Key Takeaways

The law governing security interests in personal property is Article 9 of the UCC, which defines a security interest as an interest in personal property or fixtures that secures payment or performance of an obligation. Article 9 lumps together all the former types of security devices, including the pledge, chattel mortgage, and conditional sale.

Five types of tangible property may serve as collateral: (1) consumer goods, (2) equipment, (3) farm products, (4) inventory, and (5) fixtures. To create an enforceable security interest, the lender and borrower must enter into an agreement establishing the interest, and the lender must follow steps to ensure that the security interest first attaches and then is perfected. There are three general requirements for attachment: (1) there must be an authenticated agreement (or the collateral must physically be in the lender’s possession), (2) the lender must have given value, and (3) the debtor must have some rights in the collateral. Once the interest attaches, the lender has rights in the collateral superior to those of unsecured creditors. But others may defeat his interest unless he perfects the security interest. The three common ways of doing so are (1) filing a financing statement, (2) pledging collateral, and (3) taking a purchase-money security interest (PMSI) in consumer goods.

A financing statement is a simple notice, showing the parties’ names and addresses, the signature of the debtor, and an adequate description of the collateral. The financing statement, effective for five years, must be filed in a public office; the location of the office varies among the states.

The general priority rule is “first in time, first in right.” Priority dates from the earlier of two events: (1) filing a financing statement covering the collateral or (2) other perfection of the security interest. Several exceptions to this rule arise when creditors take a PMSI, among them, when a buyer in the ordinary course of business takes free of a security interest created by the seller.

On default, a creditor may repossess the collateral. For the most part, self-help private repossession continues to be lawful but risky. After repossession, the lender may sell the collateral or accept it in satisfaction of the debt. Any excess in the selling price above the debt amount must go to the debtor.

The Constitution gives Congress the power to legislate on bankruptcy. The current law is the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, which provides for six types of proceedings: (1) liquidation, Chapter 7; (2) adjustment of debts of a municipality, Chapter 9; (3) reorganization, Chapter 11; (4) family farmers with regular income, Chapter 12; (5) individuals with regular income, Chapter 13; and (6) cross-border bankruptcies, Chapter 15.

With some exceptions, any individual, partnership, or corporation seeking liquidation may file a voluntary petition in bankruptcy. An involuntary petition is also possible; creditors petitioning for that must meet certain criteria.

A petition operates as a stay against the debtor for lawsuits to recover claims or enforce judgments or liens. A judge will issue an order of relief and appoint a trustee, who takes over the debtor’s property and preserves security interests. To recover monies owed, creditors must file proof of claims. The trustee has certain powers to recover property for the estate that the debtor transferred before bankruptcy. These include the power to act as a hypothetical lien creditor, to avoid fraudulent transfers and voidable preferences.

The bankruptcy act sets out categories of claimants and establishes priority among them. After secured parties take their security, the priorities are (1) domestic support obligations, (2) administrative expenses, (3) gap creditor claims, (4) employees’ wages, salaries, commissions, (5) contributions to employee benefit plans, (6) grain or fish producers’ claims against a storage facility, (7) consumer deposits, (8) taxes owed to governments, (9) allowed claims for personal injury or death resulting from debtor’s driving or operating a vessel while intoxicated. After these priority claims are paid, the trustee must distribute the estate in this order: (a) unsecured creditors who filed timely, (b) unsecured creditors who filed late, (c) persons claiming fines and the like, (d) all other creditors, (e) the debtor. Most bankruptcies are no-asset, so creditors get nothing.

Under Chapter 7’s 2005 amendments, debtors must pass a means test to be eligible for relief; if they make too much money, they must file Chapter 13.

Certain property is exempt from the estate of an individual debtor. States may opt out of the federal list of exemptions and substitute their own; most have.

Once discharged, the debtor is no longer legally liable for most debts. However, some debts are not dischargeable, and bad faith by the debtor may preclude discharge. Under some circumstances, a debtor may reaffirm a discharged debt. A Chapter 7 case may be converted to Chapter 11 or 13 voluntarily, or to Chapter 11 involuntarily.

Chapter 11 provides for reorganization. Any person eligible for discharge in Chapter 7 is eligible for Chapter 11, except stockbrokers and commodity brokers; those who have too much debt to file Chapter 13 and surpass the means test for Chapter 7 file Chapter 11. Under Chapter 11, the debtor retains possession of the business and may continue to operate it with its own management unless the court appoints a trustee. The court may do so either for cause or if it is in the best interests of the creditors. The court must appoint a committee of unsecured creditors, who remain active throughout the proceeding. The debtor may file its own reorganization plan and has the exclusive right to do so within 120 days if it remains in possession. The plan must be accepted by certain proportions of each impaired class of claims and interests. It is binding on all creditors, and the debtor is discharged from all debts once the court confirms the plan.

Chapter 13 is for any individual with regular income who has difficulty paying debts; it is voluntary only; the debtor must get credit counseling. The debtor presents a payment plan to creditors, and the court appoints a trustee. The plan extends the time to pay and may reduce the size of the debt. If the creditors wind up with more in this proceeding than they would have in Chapter 7, the court is likely to approve the plan. The court may approve a stretch-out of five years. Some debts not dischargeable under Chapter 7 may be under Chapter 13.

Exercises

- Kathy Knittle borrowed $20,000 from Bank to buy inventory to sell in her knit shop and signed a security agreement listing as collateral the entire present and future inventory in the shop, including proceeds from the sale of inventory. Bank filed no financing statement. A month later, Knittle borrowed $5,000 from Creditor, who was aware of Bank’s security interest. Knittle then declared bankruptcy. Who has priority, Bank or Creditor?

- Assume the same facts as in Exercise 1, except Creditor—again, aware of Bank’s security interest—filed a financing statement to perfect its interest. Who has priority, Bank or Creditor?

- First Bank has a security interest in equipment owned by Kathy Knittle in her Knit Shop. If Kathy defaults on her loan and First Bank lawfully repossesses, what are the bank’s options? Explain.

- First Bank has a security interest in equipment owned by Kathy Knittle in her Knit Shop. If Kathy defaults on her loan and First Bank lawfully repossesses, what are the bank’s options? Explain.

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-109. ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(a)(73). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(12). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-102(44). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-203(b)(2). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-310(a). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-502, Official Comment 2. ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-504. ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-501. ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-501(a)(2). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-307(b). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-303. ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-312(e). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-312(f) and (g). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-313. ↵

- Pun intended. ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-322(a)(2). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-322(a)(1). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-324(a). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-324(b). ↵

- Uniform Commercial Code, Section 9-320(a). ↵

- 11 United States Code, Section 547. ↵

A loan for which no collateral is pledged.

The delivery of goods to a creditor as security for the debt.

Perfection by mere attachment.

The intangible entity containing all the debtor’s nonexempt property and liabilities.