14 Small Business Organizations

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify the costs and benefits of operating as a sole proprietorship

- Identify the liability and default management rules for general partnerships

- Distinguish between LPs, LLPs, and LLCs

- Understand the steps needed to form an LLC and begin a small business in practice

One of the major decisions involved in starting, or growing, a business is how to legally structure the business entity. If one does nothing, then a sole proprietorship is created. This has great flexibility but unlimited personal liability. If one starts a business with another, but takes no legal steps, a general partnership has been created. Again, this offers unlimited personal liability. In contrast, creating a business entity like an LLC takes little effort and offers the owner protection against lawsuits.

Sole Proprietorships

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should understand the following:

- Understand the costs and benefits of operating as a sole proprietorship

- Understand the concept of unlimited personal liability

If an individual starts a business by themselves without taking any legal precautions, they have created a “sole proprietorship”. This is a business in which the owner is the business. This offers great flexibility: if the owner wishes to work, they may do so. If they wish not to work, nobody will compel them. The owner can come and go as they please, set prices as they desire, hire the employees they want, and fire employees they don’t like, all without consulting other owners.

These are definitely advantages! It lets businesses be nimble, and one can start such a business without legal formalities. In fact, many small businesses in the United States begin as sole proprietorships. If you’ve began a solo business enterprise without taking other legal steps, then you created a sole proprietorship without realizing it.

At the same time, operating as a sole proprietor has major disadvantages. First, it can be hard to raise capital for the business, because you cannot offer ownership rights in the form of stock or partnership interests. Second, this type of business form has unlimited personal liability. Because the owner is the business, the owner faces unlimited personal liability for the business. If someone slips and falls on the premises because the owner was negligent in cleaning up a spill, and then sues and wins, the owner may lose their home or retirement account, or be forced into bankruptcy.

For these reasons, particularly the second, careful entrepreneurs give thought to liability as they begin a business. Some feel comfortable by purchasing liability insurance, while many others take the steps to create a business entity that offers a liability shield, such as a Limited Liability Company or LLC. Forming an LLC is relatively painless and can protect the personal assets of the owner.

Key Takeaways

Exercises

- What are the costs and benefits involved in starting a sole proprietorship?

- What does “unlimited personal liability” mean in practice?

Partnerships

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should understand the following:

- The importance of partnership and the present status of partnership law

- The tests that determine whether a partnership exists

- Partnership formation

- The operation of a partnership, including the relations among partners and relations between partners and third parties

It would be difficult to conceive of a complex society that did not operate its businesses through organizations. In this section we study partnerships, limited partnerships, and limited liability companies, and we touch on joint ventures and business trusts.

When two or more people form their own business or professional practice, they usually consider becoming partners. Partnership law defines a partnership as “the association of two or more persons to carry on as co-owners a business for profit…whether or not the persons intend to form a partnership.”[1] When we use the word partnership, we are referring to the general business partnership. There are also limited partnerships and limited liability partnerships, which are discussed later.

Partnerships are also popular as investment vehicles. Partnership law and tax law permit an investor to put capital into a limited partnership and realize tax benefits without liability for the acts of the general partners.

Even if you do not plan to work within a partnership, it can be important to understand the law that governs it. Why? Because it is possible to become someone’s partner without intending to or even realizing that a partnership has been created. Knowledge of the law can help you avoid partnership liability.

Entity Characteristics of a Partnership

Partnership law is in a state of flux: some states base their partnership law on a law called the Uniform Partnership Act (UPA) while others use the Revised Uniform Partnership Act (RUPA). These laws differ in significant ways, such as whether they treat the partnership as generally a separate legal entity (RUPA) or as merely the aggregation of the partners (UPA). In this chapter, for simplicity we will study principles from RUPA.

Partnership law (under RUPA) treats a partnership as a separate legal entity for most purposes. This means the partnership may keep business records as if it were a separate entity, it owns property as a distinct entity, it can be sued as a distinct legal entity, and its accountants may treat it as such for purposes of preparing income statements and balance sheets.When this is not the case, for example, to sue a partnership you must sue each partner. However, for tax purposes and liability purposes, the partnership remains treated as an aggregation. As such, partnerships do not pay income taxes. Instead, each partner’s distributive share, which includes income or other gain, loss, deductions, and credits, must be included in the partner’s personal income tax return, whether or not the share is actually distributed. Similarly for liability purposes, all partners are, and each one of them is, ultimately personally liable for the obligations of the partnership, without limit, which includes personal and unlimited liability. This personal liability is very distasteful, and it has been abolished, subject to some exceptions, with limited partnerships and limited liability companies, as discussed later.

Partnership Formation

The most common way of forming a partnership is expressly—that is, in words, orally or in writing. Such a partnership is called an express partnership.

Assume that three persons have decided to form a partnership to run a car dealership. Able contributes $250,000. Baker contributes the building and space in which the business will operate. Carr contributes his services; he will manage the dealership.

The first question is whether Able, Baker, and Carr must have a partnership agreement. As should be clear from the foregoing discussion, no agreement is necessary as long as the tests of partnership are met. However, they ought to have an agreement in order to spell out their rights and duties among themselves.

The agreement itself is a contract and should follow the principles and rules of contract law. Because it is intended to govern the relations of the partners toward themselves and their business, every partnership contract should set forth clearly the following terms: (1) the name under which the partners will do business; (2) the names of the partners; (3) the nature, scope, and location of the business; (4) the capital contributions of each partner; (5) how profits and losses are to be divided; (6) how salaries, if any, are to be determined; (7) the responsibilities of each partner for managing the business; (8) limitations on the power of each partner to bind the firm; (9) the method by which a given partner may withdraw from the partnership; (10) continuation of the firm in the event of a partner’s death and the formula for paying a partnership interest to his heirs; and (11) method of dissolution.

If the parties do not provide for these in their agreement, RUPA will do it for them as the default. If the business cannot be performed within one year from the time that the agreement is entered into, the partnership agreement should be in writing to avoid invalidation under the Statute of Frauds. Most partnerships have no fixed term, however, and are partnerships “at will” and therefore not covered by the Statute of Frauds.

Implied Partnerships

An implied partnership exists when in fact there are two or more persons carrying on a business as co-owners for profit. For example, Carlos decides to paint houses during his summer break. He gathers some materials and gets several jobs. He hires Wally as a helper. Wally is very good, and pretty soon both of them are deciding what jobs to do and how much to charge, and they are splitting the profits. They have an implied partnership, without intending to create a partnership at all.

Tests of Partnership Existence

But how do we know whether an implied partnership has been created? Obviously, we know if there is an express agreement. But partnerships can come into existence quite informally, indeed, without any formality—they can be created accidentally. In contrast to the corporation, which is the creature of statute, partnership is a catchall term for a large variety of working relationships, and frequently, uncertainties arise about whether or not a particular relationship is that of partnership. The law can reduce the uncertainty in advance only at the price of severely restricting the flexibility of people to associate.

The crucial test for a partnership is: 1) the association of persons, (2) as co-owners, (3) for profit. Under (1) “persons” can include an individual, LLC, other partnership, corporation, and so on. For (2), if what two or more people own is clearly a business—including capital assets, contracts with employees or agents, an income stream, and debts incurred on behalf of the operation—a partnership exists. To establish a partnership, the ownership must be of a business, not merely of property. (So owning land with someone does not necessarily mean there is a partnership.)

For (3), of the tests used by courts to determine co-ownership, perhaps the most important is sharing of profits. Section 202(c) of RUPA provides that “a person who receives a share of the profits of a business is presumed to be a partner in the business,” but this presumption can be rebutted by showing that the share of the profits paid out was (1) to repay a debt; (2) wages or compensation to an independent contractor; (3) rent; (4) an annuity, retirement, or health benefit to a representative of a deceased or retired partner; (5) interest on a loan, or rights to income, proceeds, or increase in value from collateral; or (5) for the sale of the goodwill of a business or other property.

Partnership Operation

Most of the rules discussed in this section apply unless otherwise agreed, and they are really intended for the small firm.“The basic mission of RUPA is to serve the small firm. Large partnerships can fend for themselves by drafting partnership agreements that suit their special needs.”[2]

Duties Partners Owe Each Other

Among the duties partners owe each other, six may be called out here: (1) the duty to serve, (2) the duty of loyalty, (3) the duty of care, (4) the duty of obedience, (5) the duty to inform copartners, and (6) the duty to account to the partnership. These are all very similar to the duty owed by an agent to the principal, as partnership law is based on agency concepts.

In general, this requires partners to put the firm’s interests ahead of their own. Partners are fiduciaries as to each other and as to the partnership, and as such, they owe a fiduciary duty^[The highest duty of good faith and trust, imposed on partners as to each other and the firm.] to each other and the partnership. Judge Benjamin Cardozo, in an often-quoted phrase, called the fiduciary duty “something stricter than the morals of the marketplace. Not honesty alone, but the punctilio of an honor the most sensitive, is then the standard of behavior.”[3] Breach of the fiduciary duty gives rise to a claim for compensatory, consequential, and incidental damages; recoupment of compensation; and—rarely—punitive damages.

The duty of loyalty means, again, that partners must put the firm’s interest above their own. Thus it is held that a partner

- may not compete with the partnership,

- may not make a secret profit while doing partnership business,

- must maintain the confidentiality of partnership information.

This is certainly not a comprehensive list, and courts will determine on a case-by-case basis whether the duty of loyalty has been breached. Stemming from its roots in agency law, partnership law also imposes a duty of care on partners. Partners are to faithfully serve to the best of their ability.

Partnership Rights

Profits and losses may be shared according to any formula on which the partners agree. For example, the partnership agreement may provide that two senior partners are entitled to 35 percent each of the profit from the year and the two junior partners are entitled to 15 percent each. The next year the percentages will be adjusted based on such things as number of new clients garnered, number of billable hours, or amount of income generated. Eventually, the senior partners might retire and each be entitled to 2 percent of the firm’s income, and the previous junior partners become senior, with new junior partners admitted.

If no provision is stated, then under RUPA Section 401(b), “each partner is entitled to an equal share of the partnership profits and is chargeable with a share of the partnership losses in proportion to the partner’s share of the profits.” The right to share in the profits is the reason people want to “make partner”: a partner will reap the benefits of other partners’ successes (and pay for their failures too). A person working for the firm who is not a partner is an associate and usually only gets only a salary.

All partners are entitled to share equally in the management and conduct of the business, unless the partnership agreement provides otherwise. The partnership agreement could be structured to delegate more decision-making power to one class of partners (senior partners) than to others (junior partners), or it may give more voting weight to certain individuals. For example, perhaps those with the most experience will, for the first four years after a new partner is admitted, have more voting weight than the new partner.

A business partnership is often analogized to a marriage partnership. In both there is a relationship of trust and confidence between (or among) the parties; in both the poor judgment, negligence, or dishonesty of one can create liabilities on the other(s). In a good marriage or good partnership, the partners are friends, whatever else the legal relationship imposes. Thus no one is compelled to accept a partner against his or her will. Section 401(i) of RUPA provides, “A person may become a partner only with the consent of all of the partners.” The freedom to select new partners, however, is not absolute. In 1984, the Supreme Court held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—which prohibits discrimination in employment based on race, religion, national origin, or sex—applies to partnerships.[4]

Key Takeaways

Partnership law defines a partnership as “an association of two or more persons to carry on as co-owners a business for profit.” The Revised Uniform Partnership Act (RUPA) assumes a partnership is an entity, but it applies one crucial rule characteristic of the aggregate theory: the partners are ultimately liable for the partnership’s obligations. Thus a partnership may keep business records as if it were a legal entity, may hold real estate in the partnership name, and may sue and be sued in federal court and in many state courts in the partnership name.

Partnerships may be created informally. Among the clues to the existence of a partnership are (1) co-ownership of a business, (2) sharing of profits, (3) right to participate in decision making, (4) duty to share liabilities, and (5) manner in which the business is operated. A partnership may also be formed by implication.

No special rules govern the partnership agreement. As a practical matter, it should sufficiently spell out who the partners are, under what name they will conduct their business, the nature and scope of the business, capital contributions of each partner, how profits are to be divided, and similar pertinent provisions. An oral agreement to form a partnership is valid unless the business cannot be performed wholly within one year from the time that the agreement is made. However, most partnerships have no fixed terms and hence are “at-will” partnerships not subject to the Statute of Frauds.

Partners have important duties in a partnership, including (1) the duty to serve—that is, to devote herself to the work of the partnership; (2) the duty of loyalty, which is informed by the fiduciary standard: the obligation to act always in the best interest of the partnership and not in one’s own best interest; (3) the duty of care—that is, to act as a reasonably prudent partner would; (4) the duty of obedience not to breach any aspect of the agreement or act without authority; (5) the duty to inform copartners; and (6) the duty to account to the partnership.

Exercises

- Why is it necessary—or at least useful—to have tests to determine whether a partnership exists?

- What is the “fiduciary duty,” and why is it imposed on some partners’ actions with the partnership?

Special Forms of Partnerships

Learning Objectives

- The basics of limited partnerships

- The basics of limited liability partnerships

- How these differ from general partnerships

This and the following section provide a bridge between the partnership and the corporate form. It explores several types of associations that are hybrid forms—that is, they share some aspects of partnerships and some of corporations. Corporations afford the inestimable benefit of limited liability, partnerships the inestimable benefit of limited taxation. Businesspeople always seek to limit their risk and their taxation.

Limited Partnerships

The limited partnership is attractive because of its treatment of taxation and its imposition of limited liability on its limited partners.

A limited partnership (LP) is defined as “a partnership formed by two or more persons under the laws of a State and having one or more general partners and one or more limited partners.”[5] The form tends to be attractive in business situations that focus on a single or limited-term project, such as making a movie or developing real estate; it is also widely used by private equity firms.

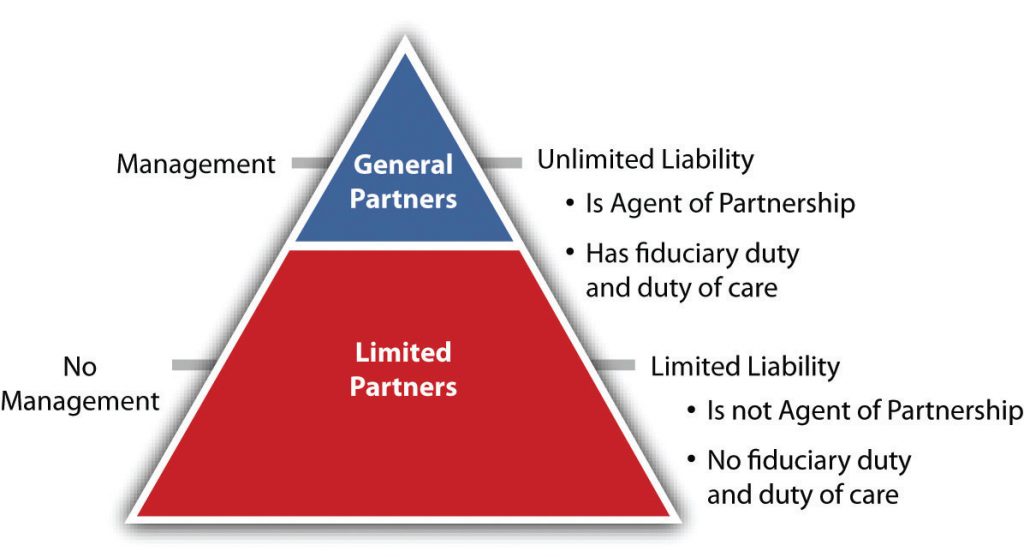

Unlike a general partnership, a limited partnership is created in accordance with the state statute authorizing it. There are two categories of partners: limited and general. The limited partners capitalize the business and the general partners run it.

The act requires that the firm’s promoters file a certificate of limited partnership with the secretary of state; if they do not, or if the certificate is substantially defective, a general partnership is created. The certificate must be signed by all general partners. It must include the name of the limited partnership (which must include the words limited partnership so the world knows there are owners of the firm who are not liable beyond their contribution) and the names and business addresses of the general partners. If there are any changes in the general partners, the certificate must be amended. The general partner may be, and often is, a corporation. Having a general partner be a corporation achieves the goal of limited liability for everyone, but it is somewhat of a “clunky” arrangement. That problem is obviated in the limited liability company, discussed below.

Any natural person, partnership, limited partnership (domestic or foreign), trust, estate, association, or corporation may become a partner of a limited partnership.

The control of the limited partnership is in the hands of the general partners, which may—as noted—be partnerships or corporations. A limited partner who exercises any significant control can incur liability like a general partner as to third parties who believed she was one (the “control rule”). However, among the things a limited partner could do that would not risk the loss of insulation from personal liability were these “safe harbors”:

- Acting as an agent, employee, or contractor for the firm; or being an officer, director, or shareholder of a corporate general partner

- Consulting with the general partner of the firm

- Requesting or attending a meeting of partners

- Being a surety for the firm

- Voting on amendments to the agreement, on dissolution or winding up the partnership, on loans to the partnership, on a change in its nature of business, on removing or admitting a general or limited partner

General partners owe fiduciary duties to other general partners, the firm, and the limited partners; limited partners who do not exercise control do not owe fiduciary duties.

Unless the partnership agreement provides otherwise (it usually does), the admission of additional limited partners requires the written consent of all. A general partner may withdraw at any time with written notice; if withdrawal is a violation of the agreement, the limited partnership has a right to claim of damages. A limited partner can withdraw any time after six months’ notice to each general partner, and the withdrawing partner is entitled to any distribution as per the agreement or, if none, to the fair value of the interest based on the right to share in distributions.

The general partners are liable as in a general partnership, and they have the same fiduciary duty and duty of care as partners in a general partnership. The limited partners are only liable up to the amount of their capital contribution, provided the surname of the limited partner does not appear in the partnership name (unless their name is coincidentally the same as that of one of the general partners whose name does appear) and provided the limited partner does not participate in control of the firm.

Limited Liability Partnerships

In 1991, Texas enacted the first limited liability partnership (LLP) statute, largely in response to the liability that had been imposed on partners in partnerships sued by government agencies in relation to massive savings and loan failures in the 1980s.[6] (Here we see an example of the legislature allowing business owners to externalize the risks of business operation.) More broadly, the success of the limited liability company discussed below attracted the attention of professionals like accountants, lawyers, and doctors who sought insulation from personal liability for the mistakes or malpractice of their partners. Their wish was granted with the adoption in all states of statutes authorizing the creation of the limited liability partnership in the early 1990s.

Members of a partnership (only a majority is required) who want to form an LLP must file with the secretary of state; the name of the firm must include “limited liability partnership” or “LLP” to notify the public that its members will not stand personally for the firm’s liabilities.

As noted, the purpose of the LLP form of business is to afford insulation from liability for its members. A typical statute provides as follows: “Any obligation of a partnership incurred while the partnership is a limited liability partnership, whether arising in contract, tort or otherwise, is solely the obligation of the partnership. A partner is not personally liable, directly or indirectly, by way of indemnification, contribution, assessment or otherwise, for such an obligation solely by reason of being or so acting as a partner.”[7]

However, the statutes vary. The early ones only allowed limited liability for negligent acts and retained unlimited liability for other acts, such as malpractice, misconduct, or wrongful acts by partners, employees, or agents. The second wave eliminated all these as grounds for unlimited liability, leaving only breaches of ordinary contract obligation. These two types of legislation are called partial shield statutes. The third wave of LLP legislation offered full shield protection—no unlimited liability at all. Needless to say, the full-shield type has been most popular and most widely adopted. Still, however, many statutes require specified amounts of professional malpractice insurance, and partners remain fully liable for their own negligence or for wrongful acts of those in the LLP whom they supervise.

In other respects, the LLP is like a partnership.

Key Takeaways

Exercises

- Why does the fact that the limited liability company provides limited liability for some of its members mean that a state certificate must be filed?

- What liability has the general partner? The limited partner?

- Why isn’t the limited partnership an entirely satisfactory solution to the liability problem of the partnership?

LLCs and S-Corps

The limited liability company (LLC) gained sweeping popularity in the late twentieth century because it combines the best aspects of partnership and the best aspects of corporations: it allows all its owners (members) insulation from personal liability and pass-through (conduit) taxation. The first efforts to form LLCs were thwarted by IRS rulings that the business form was too much like a corporation to escape corporate tax complications. Tinkering by promoters of the LLC concept and flexibility by the IRS solved those problems in interesting and creative ways.

Creating an LLC

An LLC is created according to the statute of the state in which it is formed. It is required that the LLC members file a “certificate of organization” with the secretary of state, and the name must indicate that it is a limited liability company. Partnerships and limited partnerships may convert to LLCs; the partners’ previous liability under the other organizational forms is not affected, but going forward, limited liability is provided. The members’ operating agreement spells out how the business will be run; it is subordinate to state and federal law. Unless otherwise agreed, the operating agreement can be amended only by unanimous vote. The LLC is an entity. Foreign LLCs must register with the secretary of state before doing business in a “foreign” state, or they cannot sue in state courts.

As compared with corporations, the LLC is not a good form if the owners expect to have multiple investors or to raise money from the public. The typical LLC has relatively few members (six or seven at most), all of whom usually are engaged in running the firm.

Most early LLC statutes, at least, prohibited their use by professionals. That is, practitioners who need professional licenses, such as certified public accountants, lawyers, doctors, architects, chiropractors, and the like, could not use this form because of concern about what would happen to the standards of practice if such people could avoid legitimate malpractice claims. For that reason, the limited liability partnership was invented.

Capitalization is like a partnership: members contribute capital to the firm according to their agreement. As in a partnership, the LLC property is not specific to any member, but each has a personal property interest in general. Contributions may be in the form of cash, property or services rendered, or a promise to render them in the future.

Controlling an LLC

The LLC operating agreement may provide for either a member-managed LLC or a manager-managed (centralized) LLC. If the former, all members have actual and apparent authority to bind the LLC to contracts on its behalf, as in a partnership, and all members’ votes have equal weight unless otherwise agreed. Member-managers have duty of care and a fiduciary duty, though the parameters of those duties vary from state to state. If the firm is manager managed, only managers have authority to bind the firm; the managers have the duty of care and fiduciary duty, but the nonmanager members usually do not. Some states’ statutes provide that voting is based on the financial interests of the members. Most statutes provide that any extraordinary firm decisions be voted on by all members (e.g., amend the agreement, admit new members, sell all the assets prior to dissolution, merge with another entity). Members can make their own rules without the structural requirements (e.g., voting rights, notice, quorum, approval of major decisions) imposed under state corporate law.

One of the real benefits of the LLC as compared with the corporation is that no annual meetings are required, and no minutes need to be kept. Often, owners of small corporations ignore these formalities to their peril, but with the LLC there are no worries about such record keeping.

Distributions are allocated among members of an LLC according to the operating agreement; managing partners may be paid for their services. Absent an agreement, distributions are allocated among members in proportion to the values of contributions made by them or required to be made by them. Upon a member’s dissociation that does not cause dissolution, a dissociating member has the right to distribution as provided in the agreement, or—if no agreement—the right to receive the fair value of the member’s interest within a reasonable time after dissociation. No distributions are allowed if making them would cause the LLC to become insolvent.

Liability

The great accomplishment of the LLC is, again, to achieve limited liability for all its members: no general partner hangs out with liability exposure.

Members are not liable to third parties for contracts made by the firm or for torts committed in the scope of business (but of course a person is always liable for her own torts), regardless of the owner’s level of participation—unlike a limited partnership, where the general partner is liable. Third parties’ only recourse is as against the firm’s property.

Unless the operating agreement provides otherwise, members and managers of the LLC are generally not liable to the firm or its members except for acts or omissions constituting gross negligence, intentional misconduct, or knowing violations of the law. Members and managers, though, must account to the firm for any personal profit or benefit derived from activities not consented to by a majority of disinterested members or managers from the conduct of the firm’s business or member’s or managers use of firm property—which is the same as in partnership law.

Taxation

Assuming the LLC is properly formed so that it is not too much like a corporation, it will—upon its members’ election—be treated like a partnership for tax purposes.

S-Corporations

The sub-S corporation or the S corporation gets its name from the IRS Code, Chapter 1, Subchapter S. It was authorized by Congress in 1958 to help small corporations and to stem the economic and cultural influence of the relatively few, but increasingly powerful, huge multinational corporations.

The S corporation is a regular corporation created upon application to the appropriate secretary of state’s office and operated according to its bylaws and shareholders’ agreements. There are, however, some limits on how the business is set up, among them the following:

- It must be incorporated in the United States.

- It cannot have more than one hundred shareholders (a married couple counts as one shareholder).

- The only shareholders are individuals, estates, certain exempt organizations, or certain trusts.

- Only US citizens and resident aliens may be shareholders.

- The corporation has only one class of stock.

- With some exceptions, it cannot be a bank, thrift institution, or insurance company.

- All shareholders must consent to the S corporation election.

- It is capitalized as is a regular corporation.

The owners of the S corporation have limited liability. For taxation, the S corporation pays no corporate income tax (unless it has a lot of passive income). The S corporation’s shareholders include on their personal income statements, and pay tax on, their share of the corporation’s separately stated items of income, deduction, and loss. That is, the S corporation avoids the dreaded double taxation of corporate income.

Chapter Summary and Exercises

Summary

Beginning a business as a sole proprietor is simple: simply start doing business. At the same time, the risk of unlimited personal liability should give hesitancy to this approach. Many business entities offer a liability shield at relatively little cost or effort.

Partnerships may also be created informally. Among the clues to the existence of a partnership are (1) co-ownership of a business, (2) sharing of profits, (3) right to participate in decision making, (4) duty to share liabilities, and (5) manner in which the business is operated. A partnership may also be formed by implication; it may be formed by estoppel when a third party reasonably relies on a representation that a partnership in fact exists. Similar to sole proprietorships, partnerships offer unlimited joint and several liability.

Between partnerships and corporations lie a variety of hybrid business forms: limited partnerships, sub-S corporations, limited liability companies, limited liability partnerships, and limited liability limited partnerships. These business forms were invented to achieve, as much as possible, the corporate benefits of limited liability, centralized control, and easy transfer of ownership interest with the tax treatment of a partnership.

Limited partnerships were recognized in the early twentieth century. These entities, not subject to double taxation, are composed of one or more general partners and one or more limited partners. The general partner controls the firm and is liable like a partner in a general partnership; the limited partners are investors and have little say in the daily operations of the firm. If they get too involved, they lose their status as limited partners. The general partner, though, can be a corporation, which finesses the liability problem. A limited partnership comes into existence only when a certificate of limited partnership is filed with the state.

In the mid-twentieth century, Congress was importuned to allow small corporations the benefit of pass-through taxation. It created the sub-S corporation (referring to a section of the IRS code). It affords the benefits of taxation like a partnership and limited liability for its members, but there are several inconvenient limitations on how sub-S corporations can be set up and operate.

The 1990s saw the limited liability company become the entity of choice for many businesspeople. It deftly combines limited liability for all owners—managers and nonmanagers—with pass-through taxation and has none of the restrictions perceived to hobble the sub-S corporate form. Careful crafting of the firm’s bylaws and operating certificate allow it to combine the best of all possible business forms. There remained, though, one fly in the ointment: most states did not allow professionals to form limited liability companies (LLCs).

This last barrier was hurtled with the development of the limited liability partnership. This form, though mostly governed by partnership law, eschews the vicarious liability of nonacting partners for another’s torts, malpractice, or partnership breaches of contract. The extent to which such exoneration from liability presents a moral hazard—allowing bad actors to escape their just liability—is a matter of concern.

Exercises

- Why does the name of the LLC have to include an indication that it is an LLC?

- Yolanda and Zachary decided to restructure their small bookstore as a limited partnership, called “Y to Z’s Books, LP.” Under their new arrangement, Yolanda contributed a new infusion of $300; she was named the general partner. Zachary contributed $300 also, and he was named the limited partner: Yolanda was to manage the store on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and Zachary to manage it on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. Y to Z Books, LP failed to pay $800 owing to Vendor. Moreover, within a few weeks, Y to Z’s Books became insolvent. Who is liable for the damages to Vendor?

- What result would be obtained in Exercise 2 if Yolanda and Zachary had formed a limited liability company?

- Suppose Yolanda and Zachary had formed a limited liability partnership. What result would be obtained then?

- Bellamy, Carlisle, and Davidson formed a limited partnership. Bellamy and Carlisle were the general partners and Davidson the limited partner. They contributed capital in the amounts of $100,000, $100,000, and $200,000, respectively, but then could not agree on a profit-sharing formula. At the end of the first year, how should they divide their profits?

- Revised Uniform Partnership Act, Section 202(a). ↵

- Donald J. Weidner, “RUPA and Fiduciary Duty: The Texture of Relationship,” Law and Contemporary Problems 58, no. 2 (1995): 81, 83. ↵

- Meinhard v. Salmon, 164 N.E. 545 (N.Y. 1928). ↵

- Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984). ↵

- ULPA, Section 102(11). ↵

- Christine M. Przybysz, “Shielded Beyond State Limits: Examining Conflict-Of-Law Issues In Limited Liability Partnerships,” Case Western Reserve Law Review 54, no. 2 (2003): 605. ↵

- Revised Code of Washington (RCW), Section 25.05.130. ↵

A joint venture—sometimes known as a joint adventure, coadventure, joint enterprise, joint undertaking, syndicate, group, or pool—is an association of persons to carry on a particular task until completed. In essence, a joint venture is a “temporary partnership.”

The document filed with the appropriate state authority that, when approved, marks the legal existence of the limited partnership.

A partnership in which some or all partners (depending on the jurisdiction) have limited liability.

A corporation whose owners elect to have it treated as a partnership for tax purposes.