121 Citing Sources in Modern Language Association (MLA) Style

Joel Gladd

In academic essays, the most common reason why we use information from outside sources is to 1) provide important context or 2) bolster our own ideas with evidence. Evidence includes some of the following, in order of least convincing to most convincing:

- personal anecdotes

- expert testimony

- case studies

- statistical data

- facts derived from sources

- basic facts most people agree on

Notice that many of these forms derive from outside sources: expert testimony, case studies, and statistical data. Even personal anecdotes can be borrowed from outside sources, so most of our evidence is often derived from research.

There’s a famous latin saying that expresses this phenomenon: nanos giantum humeris insidentes, or “standing on the shoulders of giants.” According to the book Strategic Source in the New Economy, this metaphor can be traced to Bernard of Chartres in the twelfth century, but Isaac Newton made it popular after using it in 1676 (Keith et al 1).[1]

However, when using sources in essays geared towards an academic audience, writers are expected to 1) clearly signal that they’re relying on other writers, and then 2) cite the proper information that allows the reader to locate the original source.

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce students to the conventions of citing information in MLA Style.

Review: The Purpose of In-Text Citations

There are two functions of in-text citations:

- In-text citations signal to the reader when an idea or piece of information from your essay is not your own, but rather derived from something you’ve come across in research (whether a text, video or audio clip). In-text citations tell the reader: This is something I’ve taken from an outside source! It’s not my original idea. They protect you from plagiarism. Keep in mind all information from an outside source must be cited and not just direct quotations.

- In-text citations also tell the reader where they can locate the original source. For example, in my quote above about “standing on the shoulders of giants,” I included an in-text citation at the end, like this: (Keith, et al 1). That tells the reader this particular bit of information was from page 1 of the book, whose authors were Keith et al[2], and they can find out more about how to locate the source by looking for the Keith, et al entry in the Works Cited page.

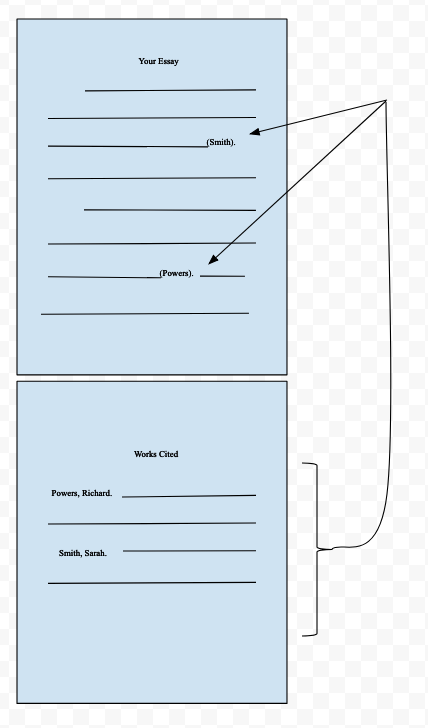

The second point is crucial. It’s important to keep in mind that in-text citations always connect the reader to the Works Cited page, where all of the technical information about the source can be found. The main purpose of the in-text citation is simply point out which particular Works Cited item is relevant.

How to punctuate in-text citations

In the chapter, “Basics of Integration,” we learned the basic rules of punctuation when including things like direct quotations. All of those rules still apply. However, whenever an in-text citation appears, the end quotation mark comes before the parenthetical citation and final punctuation comes after it.

Below is an example of passage that includes direct quotations and some summary:

Notice in the passage above how both the direct quotation and the summarized information are both cited? It’s important to remember that any information—whether paraphrased, summarized, or quoted directly—needs to be cited properly.

What information goes inside in-text citations (MLA)?

This section is unique to MLA. For APA Style, refer to the previous chapters for what information to include.

Before jumping into MLA conventions, it might help to understand why fields have different styles at all. Most students eventually realize that there are some key differences between MLA vs. APA especially, but not many appreciate why these differences exist.

When creating in-text citations, MLA asks for the author + location (Smith 12), whereas APA asks for author + year of publication (Springer, 2018). Why?

This difference in citations shows how different fields appreciate textual artifacts in different ways. APA is typically used in the sciences, where experts emphasize the date something was published. More recent publications tend to have higher weight, because scientific fields believe strongly in the progress that comes with experimental studies.

MLA is used in the Humanities, where experts practice a lot of close reading and emphasize contextual information that surrounds evidence. This text-based emphasize prioritizes the location of the information, rather than the date. The assumption is that a typical Humanities reader will want to track down the precise place where a quote or piece of information is found, because close readers care a lot about context.

Most common MLA in-text citation: Author + Location

When citing a source in an MLA-formatted essay, the most common information to include is the author’s last name and the location of the information (usually the page number). For online sources, the most common in-text citation is simply the author’s last name.

According to the book String Theory, modern physics has trouble combining general relativity with quantum mechanics (Powers 81).

The Author is: Powers

The location is: page 81

The in-text citation above includes a number because that particular source happens to have page numbers. But many online articles either don’t have authors or obvious locations. Below offers a longer list of how to do MLA in-text citations. First, though, here are some key points:

- The most common in-text citation for print sources, academic articles, and reports is (Author + location), where the location is a page number. Example: (Powers 81).

- It’s common for online articles to not have page numbers or stable locations. If there’s no location, just include the last name of the author. Example: (Smith).

- If there’s no author, include the title of the article. Example: (“Rising Rates of Caffeine Use Among U.S. Teens”).

Sources that have already been introduced

In the chapter on the Basics of Integration, we learned that it’s often helpful to use signal phrases when introducing key quotes from a source. Since a signal phrase—which always includes the author’s last name—clearly signals where the information is from, it’s no longer necessary to include that information in the in-text citation.

According to Jeffrey Blankship, the fork is “an inferior way to pick up meat” (5).

Some argue the fork is “an inferior way to pick up meat” (Blankship 5).

Sources with no known author

When a source has no known author, use a shortened title of the work instead of an author name. For shorter works such as articles, the convention is to place it in quotes. For longer works, use italics.

Multiple authors

When citing two authors, list the last names either in the text or in the parenthetical citation.

Williams and Powers attempted to show that string theory was a viable way to combine general relativity and quantum mechanics (9).

Some have argued that string theory is a viable way to combine general relativity and quantum mechanics (Williams and Powers 9).

Source with three or more authors

Use the first author’s last name, followed by et al.

According to Weston et al., “Recent sales are due more to government stimulus than increased demand” (19).

Some argue that “[r]ecent sales are due more to government stimulus than increased demand” (Weston et al. 19).

Time-based media sources

When creating in-text citations for media, such as a podcast or video, include the author information along with a time stamp. (Smith 00:02:15-00:02:35).

When a citation is not needed

Not every piece of information needs to be cited. Here are some exceptions:

- well-known quotations

- common proverbs (such as the Golden Rule)

- common knowledge (e.g., about gravity)

- commonly-accepted facts (e.g., when Julius Caesar was born)

When incorporating “common knowledge,” however, keep your audience in mind. Specialized audiences may view certain common ideas with more skepticism than others.

Video Tutorial for In-Text Citations

Formatting MLA in-text citations can seem overwhelming at first. It may help to watch a video, such as this one:

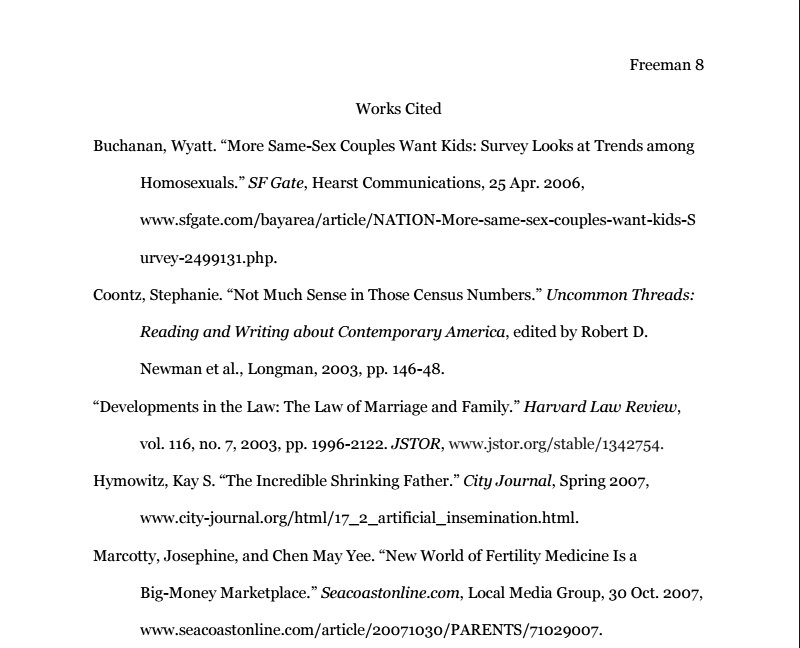

MLA Works Cited

A Works Cited page supplements in-text citations. This page comes at the end of your essay and it contains a list of bibliographic citations for all of the sources. The citations are organized alphabetically by first word of the citation. Here’s an example Works Cited page in MLA Style:

According to the official MLA Style Center, there are certain “core elements” that should be included for each source in your Works Cited page. These include:

- Author.

- Title of source.

- Title of container,

- Other contributors,

- Version,

- Number,

- Publisher/Sponsor,

- Publication date,

- Location.

Notice how each of the elements above is followed by a period or comma? That provides hints for how to format your citations. Let’s look at one of the examples above, from the sample Works Cited page, to see how this works.

- Author = Marcotty, Joseph, and Chen May Yee.

- Title of source = “New World of Fertility Medicine Is a Big-Money Marketplace.”

- Title of container = Seacoastonline.com,

- Other contributors, [NA]

- Version, [NA]

- Number, [NA]

- Publisher/Sponsor = Local Media Group,

- Publication date = 30 Oct. 2007,

- Location = https://www.seacoastonline.com/article/20071030/PARENTS/71029007.

The citation doesn’t have elements 4, 5, or 6 because it’s not a journal article. Unless you’re citing journal articles (which tend to include bibliographic citations automatically), your source will probably look will similar to the one above. Here are some additional explanations:

- The title of the source is in quotes because it’s an article, which is considered a “shorter” work. Longer works, such as full-length books, should be in italics.

- The title of the container should be in italics.

- The publication date uses European formatting (day month year) rather than U.S. conventions.

- Unless you’re citing a print book, your source will have a URL location.

Online websites to help with bibliographic citations

The fastest and most efficient way to complete your bibliographic citations is to use a free website. I recommend one of the following resources. Warning: Links like Easybib and Zotero can help complete citations very quickly. However, you will need to verify the information is correct. If there is an edit option (or manual entry), select it, and then plug in all the information. The websites often miss information.

- Easybib: This website is easy to use because you can start by simply plugging in the web link. Make sure MLA 8 is selected, select your source type (book, journal, report, etc.), then click “Cite.” Note that there are many other websites like this! Go with whichever one you find the most intuitive.

- Zotero: Zotero and Easybib (above) are similar, but Zotero is open source and does not have advertising.

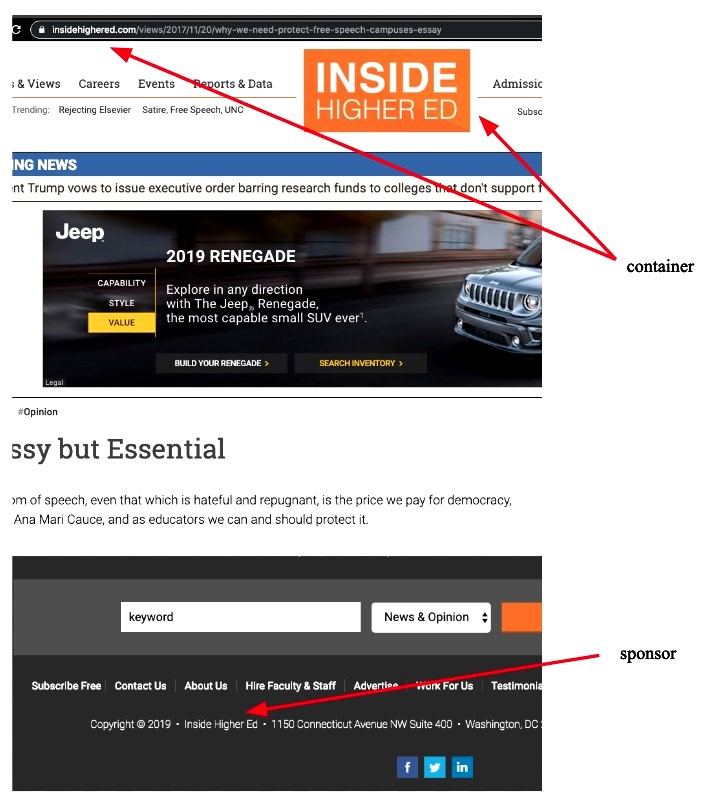

How to identify the “Container”

Even when relying on free web apps such as EasyBib, you may need to occasionally identify certain pieces of information to complete your bibliographic citation. The most common—and most important—parts you should always be able to identify are the Container and Sponsor.

Unlike earlier versions, the 8th edition of MLA refers to “containers,” which are the larger wholes in which the source is located. For example, if you want to cite a poem that is listed in a collection of poems, the individual poem is the source, while the larger collection is the container. The title of the container is usually italicized and followed by a comma, since the information that follows next describes the container.

Tips for Identifying the Sponsor/Publisher

The sponsor/publisher produces or distributes the source to the public. If there is more than one publisher, and they are all are relevant to your research, list them in your citation, separated by a forward slash (/). On most websites, the sponsor is found either in the About page or by scrolling to the very bottom of the article. The publisher/ sponsor can be verified by looking for the copyright symbol ©.

Video introduction to bibliographic citations in MLA 8

Since citation conventions can seem overwhelming at first, it may help to watch a video introduction, such as this one:

Review Exercise

- meta point: notice how I attributed this fancy saying to a published book, and that source refers to the original source? I even included the page number in parentheses. That's precisely an example of "standing on the shoulders of giants"! ↵

- et al simple means "and others." Et al is used in in-text citations when there are more than two authors for the work. ↵