2 Generate Ideas

The previous chapter, Critical Reading, suggested that college reading is often more intentional and highly targeted than other forms. In many courses, especially composition courses, much of the reading is embedded within a unit of the course that culminates in a major essay assignment. This chapter, Generate Ideas, assumes a student has been practicing critical reading strategies and has collected a number of ideas for the upcoming essay. Once they’re familiar with enough information about a topic and particular assignment, a student will be in the position to generate interesting ideas and develop a thesis statement.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer as they prepare a piece of writing. You will also be planning one of your own. The first important step is for you to tell yourself why you are writing (to inform, to explain, or some other purpose) and for whom you are writing. Write your purpose and your audience on your own sheet of paper, and keep the paper close by as you read and complete exercises in this chapter.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

Prewriting

If you think that a blank sheet of paper or a blinking cursor on the computer screen is a scary sight, you are not alone. Many writers, students, and employees find that beginning to write can be intimidating. When faced with a blank page, however, experienced writers remind themselves that writing, like other everyday activities, is a process. Every process, from writing to cooking, bike riding, and learning to use a new cell phone, will get significantly easier with practice.

Just as you need a recipe, ingredients, and proper tools to cook a delicious meal, you also need a plan, resources, and adequate time to create a good written composition. In other words, writing is a process that requires following steps and using strategies to accomplish your goals.

Effective writing can be simply described as good ideas that are expressed well and arranged in the proper order. This chapter will give you the chance to work on all these important aspects of writing. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, this chapter covers several: identifying your topic and asking questions, critical reading, freewriting, brainstorming, and mapping. Using the strategies in this chapter can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

Identify Your Topic and Formulate Related Questions

In addition to understanding that writing is a process, writers also understand that identifying the topic (sometimes called the “scope”) for an assignment is an essential step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A good topic not only covers what an assignment will be about but also fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience.

Add a line for topic to your worksheet:

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

My topic: ____________________________________________

However, general topics, such as “mass media” or “happiness”, are so vague that it can be difficult to get started on a project. Many students have been given topical assignments before, such as “What does the word ‘freedom’ mean to you?” or “Write about ‘Love'”. Sometimes college applications ask students to write their personal essay sample based on a random topic that’s intentionally vague, because very broad topics allow students to go in nearly any direction they wish, a condition ripe for expressing voice. When writing within college courses, these kinds of open-ended topical assignments are much rarer. More often, an instructor will assign an essay and offer guiding questions; or, students in a research course will be tasked with formulating interesting questions to help drive original research. One way or the other, it’s incredibly important that a student clearly identifies pertinent questions as soon as possible in the writing process. Each stage is driven by asking and then attempting to answer clear questions.

Add a few related questions underneath your topic.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

My topic: ____________________________________________

Related questions: ____________________________________________

Freewriting

Freewriting is an exercise in which you write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually three to five minutes). During the time limit, you may jot down any thoughts that come to your mind. Try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over until you come up with a new thought.

Freewriting, and writing more generally, often comes easier when you have a personal connection with the topic you have chosen. Identifying personal experiences and observations that connect with your topic also cultivates voice, an important aspect of rhetorical persuasion.

You may also think about readings that you have enjoyed or that have challenged your thinking. Doing this may lead your thoughts in interesting directions.

Quickly recording your thoughts on paper will help you discover what you have to say about a topic. When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and un-selfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

Exercise

On the same worksheet as you started above, which identified the Purpose, Audience, Topic, and Related Questions, add a section below it titled “Freewrite”. Then freewrite about about your personal experience with the topic and related questions. Write without stopping, for 5 minutes. When freewriting, try to be specific. If you can recount specific experiences that happened at a certain time and location, even better. If you can’t, just write about whatever comes to mind.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

My topic: ____________________________________________

Related questions: ____________________________________________

5-Minute freewrite:

Critical Reading

The previous chapter, on Critical Reading, already emphasized the importance of reading in the writing process. It figures prominently in the development of ideas and topics. Different kinds of documents can help you choose a topic and also develop that topic. For example, a magazine advertising the latest research on the threat of global warming may catch your eye in the supermarket. This cover may interest you, and you may consider global warming as a topic. Or maybe a novel’s courtroom drama sparks your curiosity of a particular lawsuit or legal controversy.

After identifying the topic and related questions, critical reading is essential to its development. While reading almost any document, you evaluate the author’s point of view by thinking about their main idea and his support. When you judge the author’s argument, you discover more about not only the author’s opinion but also your own. If this step already seems daunting, remember that even the best writers need to use prewriting strategies to generate ideas.

In research-based essay assignments, the instructor of the course may ask you track your critical reading with an annotated bibliography. Annotated Bibliographies are covered in the Research Writing portion of this textbook.

Tip

The more you plan in the beginning by reading and using prewriting strategies, the less time you may spend writing and editing later because your ideas will develop more swiftly.

One of the fundamental aspects of creative thinking is the interplay between divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking refers to the process of collecting and generating as many ideas as possible. It’s exploratory and can be playful. Similar to freewriting, divergent prewriting techniques allow the write to roam free. The most commonly utilized divergent strategies are brainstorming and idea mapping.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is similar to list making. You can make a list on your own or in a group with your classmates. Start with a blank sheet of paper (or a blank computer document) and write your general topic, issue, or debate questions across the top. Underneath your topic, make a list of related ideas or different responses to the question. Often you will find that one item can lead to the next, creating a flow of ideas that can help you narrow your focus to a more specific paper topic.

Exercise

On the same worksheet as you started above, including the purpose, audience, topic, and related questions, now add a table with one or two guiding questions at the top. Then, in the space beneath each question, jot down as many responses as possible, based on any research you’ve done so far, as well as your personal experiences, observations, and hunches.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

My topic: ____________________________________________

Related questions: ____________________________________________

Brainstorming List:

- [response 1]

- [response 2]

- [response 3]

- [response 4]

- [response 5]

In debate-driven assignments, such as an argument essay, the table might have two or three questions as the topic, corresponding to certain possible positions someone might take in response to an issue. The table should be adapted to your assignment needs.

Idea Mapping

Idea mapping allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can uncover unexpected connection. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between sources, ideas, other voices, and experiences that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map, start with your general topic, guiding question or guiding in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Then write specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them together. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

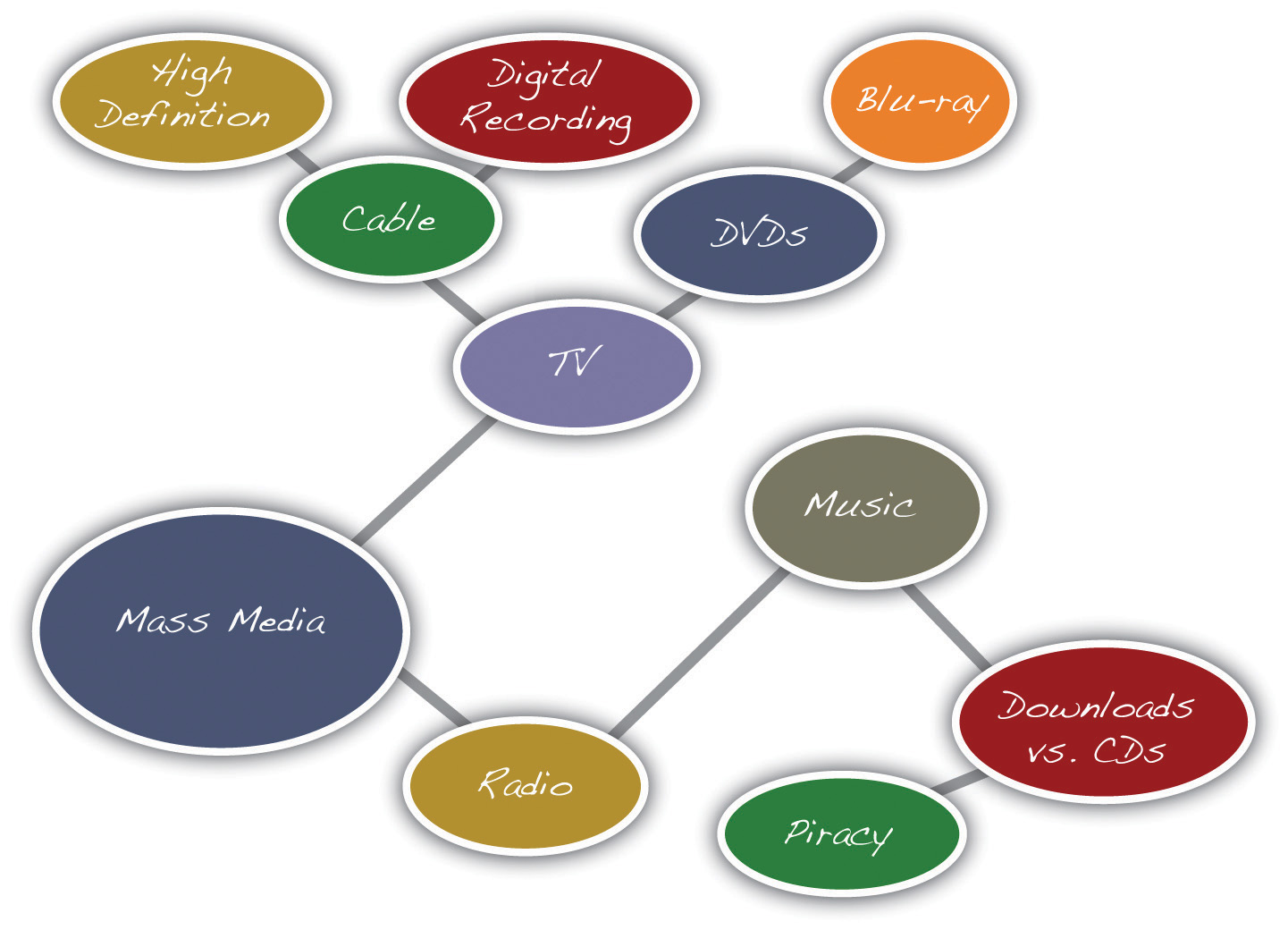

The idea map example below is fairly basic. It begins with a general topic (mass media) and then expands into several different bubbles.

Notice the largest circle contains her general topic, mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, the writer drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led the student to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy.

From this idea map, the student saw they could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

Exercise 2.1

On the same worksheet as you started above, including the purpose, audience, topic, and related questions, now add space for an idea map, with your main topic, issue, or guiding question shown in the largest circle. From there, add as many circles as you can, based on any research you’ve done so far, as well as your personal experiences, observations, and hunches. Several free web apps are available for students to use as well, such as mindmup.com.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

My topic: ____________________________________________

Related questions: ____________________________________________

Idea Map:

Moving from Divergent to Convergent Thinking

The end of the idea generation stage should result in a variety of ideas you might want to use in your own essay. In a persuasive essay, for example, some of these ideas might eventually become voices you embed as counterarguments, and others might become evidence for a particular point. What matters is that you are able to collect as many ideas as possible, based on all of the resources you have at your disposal. The next stage in the writing process, Develop a Thesis, pivots from divergent to convergent thinking.