31 Description

This morning, as I was brewing my coffee before rushing to work, I found myself hurrying up the stairs back to the bedroom, a sense of urgency in my step. I opened the door and froze—what was I doing? Did I need something from up here? I stood in confusion, trying to retrace the mental processes that had led me here, but it was all muddy.

It’s quite likely that you’ve experienced a similarly befuddling situation. This phenomenon can loosely be referred to as automatization: because we are so constantly surrounded by stimuli, our brains often go on autopilot. (We often miss even the most explicit stimuli if we are distracted, as demonstrated by the Invisible Gorilla study)

Automatization is an incredibly useful skill—we don’t have the time or capacity to take in everything at once, let alone think our own thoughts simultaneously—but it’s also troublesome. In the same way that we might run through a morning ritual absent-mindedly, like I did above, we have also been programmed to overlook tiny but striking details: the slight gradation in color of cement on the bus stop curb; the hum of the air conditioner or fluorescent lights; the weight and texture of a pen in the crook of the hand. These details, though, make experiences, people, and places unique. By focusing on the particular, we can interrupt automatization. We can become radical noticers by practicing good description.[1]

In a great variety of rhetorical situations, description is an essential rhetorical mode. Our minds latch onto detail and specificity, so effective description can help us experience a story, understand an analysis, and develop more nuance within a critical argument. Each of these situations requires different kinds and levels of description.

First Year Writing courses often dedicate at least some space to practicing description because 1) it’s employed in nearly all academic genres and disciplines, and 2) it requires a level of specificity and an attunement to detail that’s foundational to many other writing situations. It’s rare that a student will be penalized for being too specific. The opposite is usually the case. As Ken Macrorie explains in “The Poisoned Fish,” by the time students reach college they’ve often learned to race through writing assignments by deploying an academic jargon he calls “engfish,” a strange dialect that sounds fancy but doesn’t say much at all, precisely because it’s so general, abstract, or aloof from reality. An early emphasis on rich description can serve as writing salve.

Objective vs. Subjective Description

One of the traditional ways of thinking about the rhetorical nature of description is to distinguish between “objective” and “subjective” descriptions. In early 20th-century textbooks, such as F.V.N. Painter’s Elementary Guide to Literary Criticism, we get the following definitions:

Objective: “Objective description portrays objects as they exist in the external world. It points out in succession their distinguishing features.”

Subjective: “Subjective description notes the effects produced by an external object or scene on the mind and heart. The eye of the writer is turned inward rather than outward; he brings before us the thoughts, feelings, fancies that are started within his soul.”[2]

Although a bit crude, this distinction has stuck around. We can still find this framework in contemporary textbooks such as Mark Connelly’s Get Writing: Sentences and Paragraphs. Connelly provides the following example:

Objective: “The LTD 700 is a full-size sedan that seats six adults and gets 17 mpg. The base price is $65,000 and includes a GPS system, overhead DVD player, and power seats.

Subjective: “The LTD 700 is a gaudy, boxy throwback to the gas-guzzlers of the 1970s. It is grossly overpriced and laden with the high-tech toys spoiled consumers love to flaunt in front of their loser friends.”[3]

Both examples include basic details that classify them as “descriptive discourse,” but the second one contains more emotional language that more obviously reflects the judgments and values of the speaker.

Why would a writer choose to write more objectively or subjectively?

As with other rhetorical modes, what description looks like depends on the genre and purpose. It’s highly situational. We expect to find more objective-sounding descriptions in medical and law enforcement texts. A subjective description would look out of place in a medical textbook. But in personal stories, memoirs, and other more creative writing situations, objective descriptions would seem odd. Academic writer’s must carefully consider the purpose of their writing, as well as the conventions associated with the genre: is the assignment asking them to explore and communicate their subjective response to certain objects and experiences, or is it asking for a rigorously antiseptic account of the facts?

The first technique below will help you begin practicing specificity, which is important for all forms of descriptive writing. The subsequent techniques will help students practice more complex and subjective forms of description, including “thick description,” experiential language, and constraint-based scene descriptions.

Building Specificity

Activity courtesy of Mackenzie Myers

Good description lives and dies in particularities. It takes deliberate effort to refine our general ideas and memories into more focused, specific language that the reader can identify with.

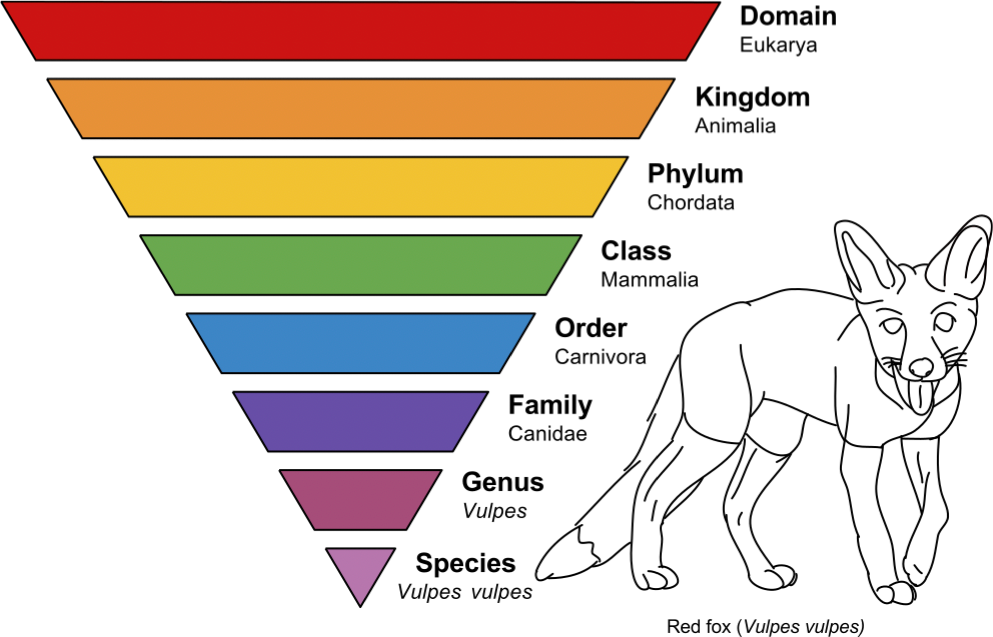

A taxonomy is a system of classification that arranges a variety of items into an order that makes sense to someone. You might remember from your biology class the ranking taxonomy based on Carl Linnaeus’ classifications, pictured here.

To practice shifting from general to specific, fill in the blanks in the taxonomy below. After you have filled in the blanks, use the bottom three rows to make your own. As you work, notice how attention to detail, even on the scale of an individual word, builds a more tangible image.

| More General | General | Specific | More Specific | |

| (example): | animal | mammal | dog | Great Dane |

| 1 | organism | conifer | Douglas fir | |

| airplane | Boeing 757 | |||

| 2 | novel | Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire | ||

| clothing | blue jeans | |||

| 3 | medical condition | respiratory infection | the common cold | |

| school | college | |||

| 4 | artist | pop singer | ||

| structure | building | The White House | ||

| 5 | coffee | Starbucks coffee | ||

| scientist | Sir Isaac Newton | |||

| 6 | ||||

Compare your answers with a classmate. What similarities do you share with other students? What differences? Why do you think this is the case? How can you apply this thinking to your own writing?

Thick Description

Thick description as a concept finds its roots in anthropology, where ethnographers seek to portray deeper context of a studied culture than simply surface appearance. In the world of writing, thick description means careful and detailed portrayal of context, emotions, and actions. It relies on specificity and rich milieu to engage the reader.

Consider the difference between these two descriptions:

| The market is busy. There is a lot of different produce. It is colorful. | vs. | Customers blur between stalls of bright green bok choy, gnarled carrots, and fiery Thai peppers. Stopping only to inspect the occasional citrus, everyone is busy, focused, industrious. |

Notice that, even though the description on the right is obviously longer, the word choice is more specific. The author names particular kinds of produce, along with specific adjectives, which sharpens the image. Further, though, the words themselves do heavy lifting—the nouns and verbs are descriptive too! “Customers blur” both implies a market (where we would expect to find “customers”) and also illustrates how busy the market is (“blur” implies speed), rather than just naming it as such.

Finally, rather than just referring to the “market” and “produce,” the second description interweaves customers, market architecture, and different kinds of produce. It’s buzzing with activity and different actants. As Norman K. Denzin explains, thick description “presents detail, context, emotion, and the webs of social relationships that join persons to one another.”[4] It is, in other words, highly contextual.

Effective thick description is rarely written the first time around; it is re-written. As you revise, consider that every word should be on purpose.

“Thick Description” Workshop

To practice a form of thick description, follow these steps:

- Choose an object you’re familiar with, and begin by listing as many objective details as possible. Practice specificity using the taxonomic method.

- Next, rewrite the description from Step 1, but now include details related to place and time. Give a setting.

- Finally, rewrite the description from Step 2, but show how individual actors (such as yourself) interact with the object.

Micro-Ethnography Workshop

An ethnography is a form of writing that uses thick description to explore a place and its associated culture. By attempting this method on a small scale, you can practice specific, focused description.

Find a place in which you can observe the people and setting without actively involving yourself. (Interesting spaces and cultures students have used before, include a poetry slam, a local bar, a dog park, and a nursing home.) You can choose a place you’ve been before or a place you’ve never been. The point here is to look at a space and a group of people more critically for the sake of detail, whether or not you already know that context.

As an ethnographer, your goal is to take in details without influencing those details. In order to stay focused, go to this place alone and refrain from using your phone or doing anything besides note-taking. Keep your attention on the people and the place.

Spend a few minutes taking notes on your general impressions of the place at this time.

- Use imagery and thick description to describe the place itself.

- What sorts of interactions do you observe? What sort of tone, affect, and language is used?

- How would you describe the overall atmosphere?

Spend a few minutes “zooming in” to identify artifacts—specific physical objects being used by the people you see.

- Use imagery and thick description to describe the specific artifacts.

- How do these parts contribute to/differentiate from/relate to the whole of the scene?

After observing, write one to two paragraphs synthesizing your observations to describe the space and culture. What do the details represent or reveal about the place and people?

Imagery and Vivid Description

Strong description helps a reader experience what you’ve experienced, whether it was an event, an interaction, or simply a place. Even though you could never capture it perfectly, you should try to approximate sensations, feelings, and details as closely as you can. Your most vivid description will be that which gives your reader a way to imagine being themselves as of your story.

Imagery is a device that you have likely encountered in your studies before: it refers to language used to “paint a scene” for the reader, directing their attention to striking details.

Here are three examples:

Bamboo walls, dwarf banana trees, silk lanterns, and a hand-size jade Buddha on a wooden table decorate the restaurant. For a moment, I imagined I was on vacation. The bright orange lantern over my table was the blazing hot sun and the cool air currents coming from the ceiling fan caused the leaves of the banana trees to brush against one another in soothing crackling sounds. (Anonymous student author, 2017. Reproduced with permission from the student author.):

The sunny midday sky calls to us all like a guilty pleasure while the warning winds of winter tug our scarves warmer around our necks; the City of Roses is painted the color of red dusk, and the setting sun casts her longing rays over the Eastern shoulders of Mt. Hood, drawing the curtains on another crimson-grey day. (Anonymous student author, 2017. Reproduced with permission from the student author.)

Flipping the switch, the lights flicker—not menacingly, but rather in a homey, imperfect manner. Hundreds of seats are sprawled out in front of a black, worn down stage. Each seat has its own unique creak, creating a symphony of groans whenever an audience takes their seats. The walls are adorned with a brown mustard yellow, and the black paint on the stage is fading and chipped. (Ross Reaume, Portland State University, 2014. Reproduced with permission from the student author).

You might notice, too, that the above examples appeal to many different senses. Beyond just visual detail, good imagery can be considered sensory language: words that help me see, but also words that help me taste, touch, smell, and hear the story. Go back and identify a word, phrase, or sentence that suggests one of these non-visual sensations; what about this line is so striking?

Imagery might also apply figurative language to describe more creatively. Devices like metaphor, simile, and personification, or hyperbole can enhance description by pushing beyond literal meanings.

Using imagery, you can better communicate specific sensations to put the reader in your shoes. To the best of your ability, avoid clichés (stock phrases that are easy to ignore) and focus on the particular (what makes a place, person, event, or object unique). To practice creating imagery, try the Imagery Inventory exercise and the Image Builder graphic organizer in the Activities section of this section.

Vivid Description Workshop

Visit a location you visit often—your classroom, your favorite café, the commuter train, etc. Isolate each of your senses and describe the sensations as thoroughly as possible. Take detailed notes in the organizer below or use a voice-recording app on your phone to talk through each of your sensations.

| Sense | Sensation |

| Sight |

|

| Sound |

|

| Smell |

|

| Touch |

|

| Taste |

|

Now, write a paragraph that synthesizes three or more of your sensory details. Which details were easiest to identify? Which make for the most striking descriptive language? Which will bring the most vivid sensations to your reader’s mind?

Description Exercises for Story-Telling

This activity is a modified version of one by Daniel Hershel.

This exercise asks you to write a scene, following specific instructions, about a place of your choice. There is no such thing as a step-by-step guide to descriptive writing; instead, the detailed instructions that follow are challenges that will force you to think differently while you’re writing. The constraints of the directions may help you to discover new aspects of this topic since you are following the sentence-level prompts even as you develop your content.

- Bring your place to mind. Focus on “seeing” or “feeling” your place.

- For a title, choose an emotion or a color that represents this place to you.

- For a first line starter, choose one of the following and complete the sentence:

-

-

- You stand there…

- When I’m here, I know that…

- Every time…

- I [see/smell/hear/feel/taste] …

- We had been…

- I think sometimes…

-

4. After your first sentence, create your scene, writing the sentences according to the following directions:

- Sentence 2: Write a sentence with a color in it.

- Sentence 3: Write a sentence with a part of the body in it.

- Sentence 4: Write a sentence with a simile (a comparison using like or as)

- Sentence 5: Write a sentence of over twenty-five words.

- Sentence 6: Write a sentence of under eight words.

- Sentence 7: Write a sentence with a piece of clothing in it.

- Sentence 8: Write a sentence with a wish in it.

- Sentence 9: Write a sentence with an animal in it.

- Sentence 10: Write a sentence in which three or more words alliterate; that is, they begin with the same initial consonant: “She has been left, lately, with less and less time to think….”

- Sentence 11: Write a sentence with two commas.

- Sentence 12: Write a sentence with a smell and a color in it.

- Sentence 13: Write a sentence without using the letter “e.”

- Sentence 14: Write a sentence with a simile.

- Sentence 15: Write a sentence that could carry an exclamation point (but don’t use the exclamation point).

- Sentence 16: Write a sentence to end this portrait that uses the word or words you chose for a title.

5. Read over your scene and mark words/phrases that surprised you, especially those rich with possibilities (themes, ironies, etc.) that you could develop.

6. On the right side of the page, for each word/passage you marked, interpret the symbols, name the themes that your description and detail suggest, note any significant meaning you see in your description.

7. On a separate sheet of paper, rewrite the scene you have created as a more thorough and cohesive piece in whatever genre you desire. You may add sentences and transitional words/phrases to help the piece flow.

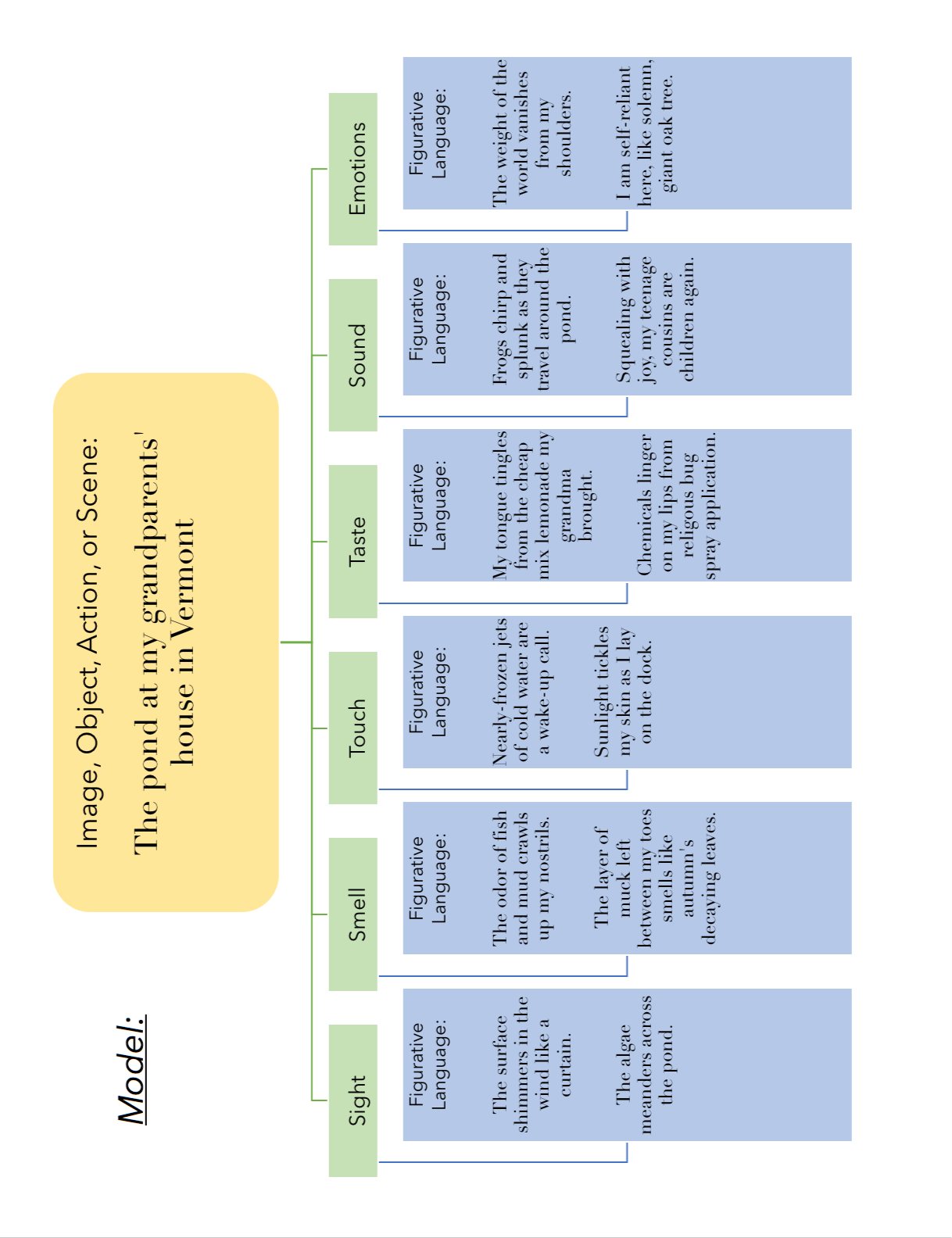

Image Building for Stories

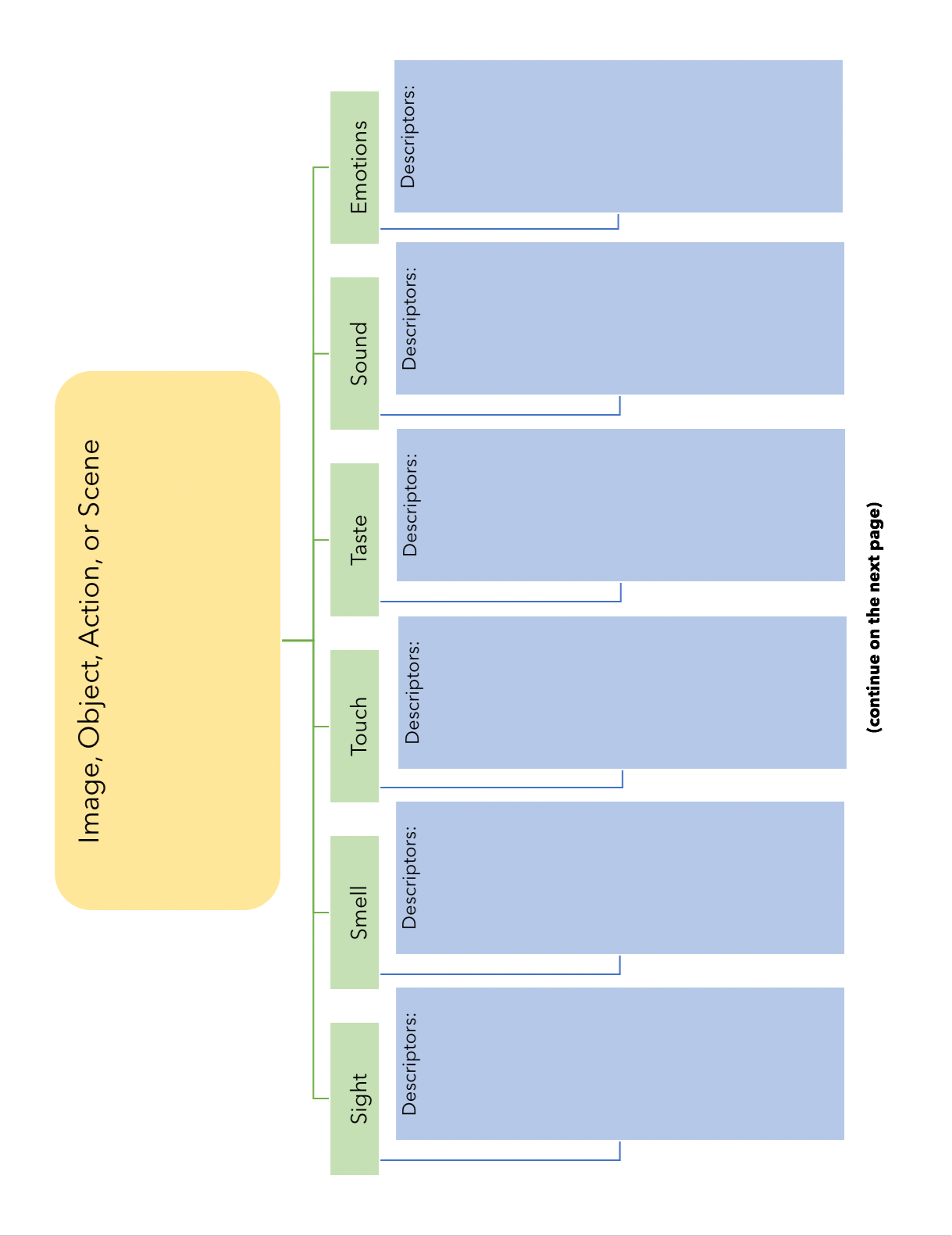

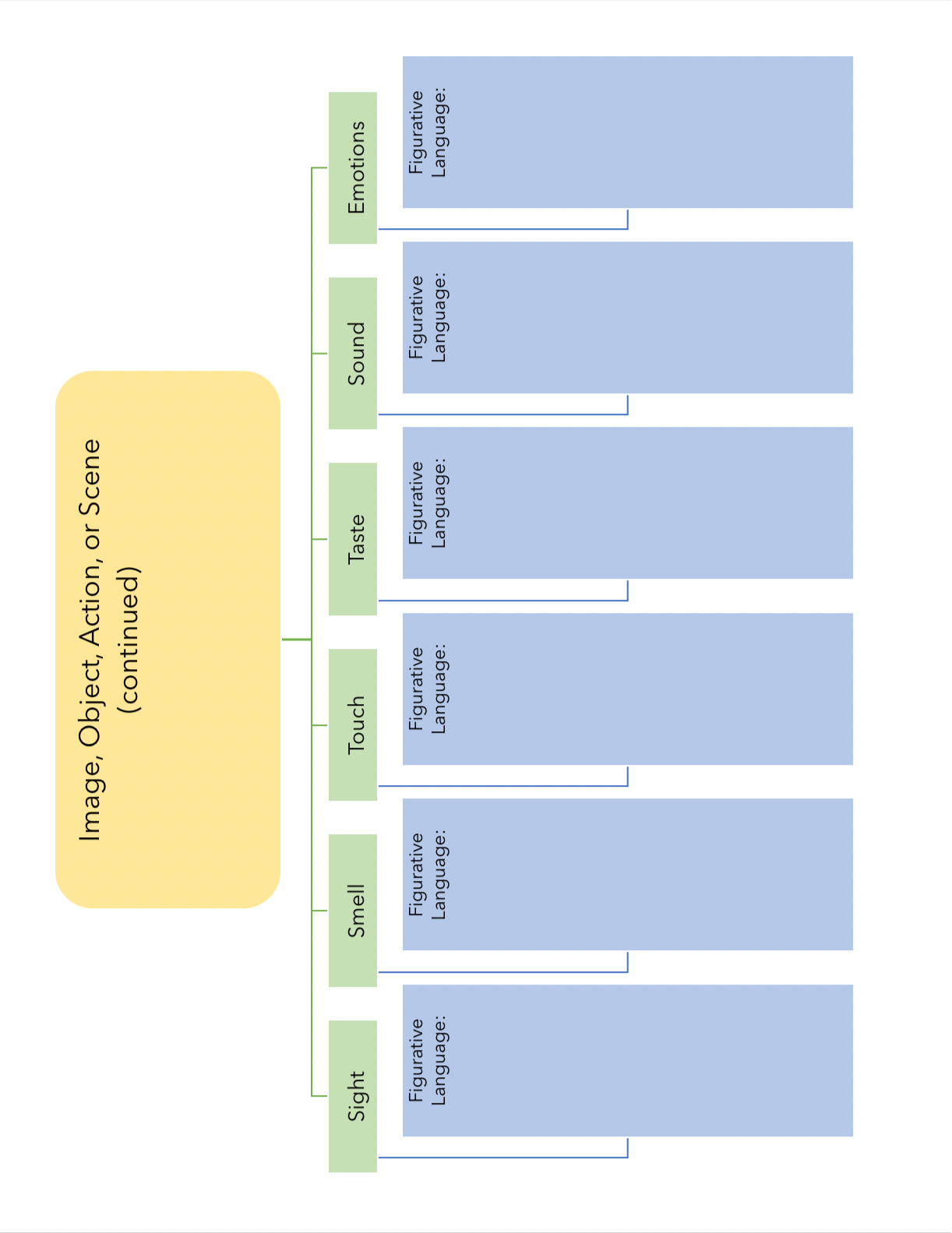

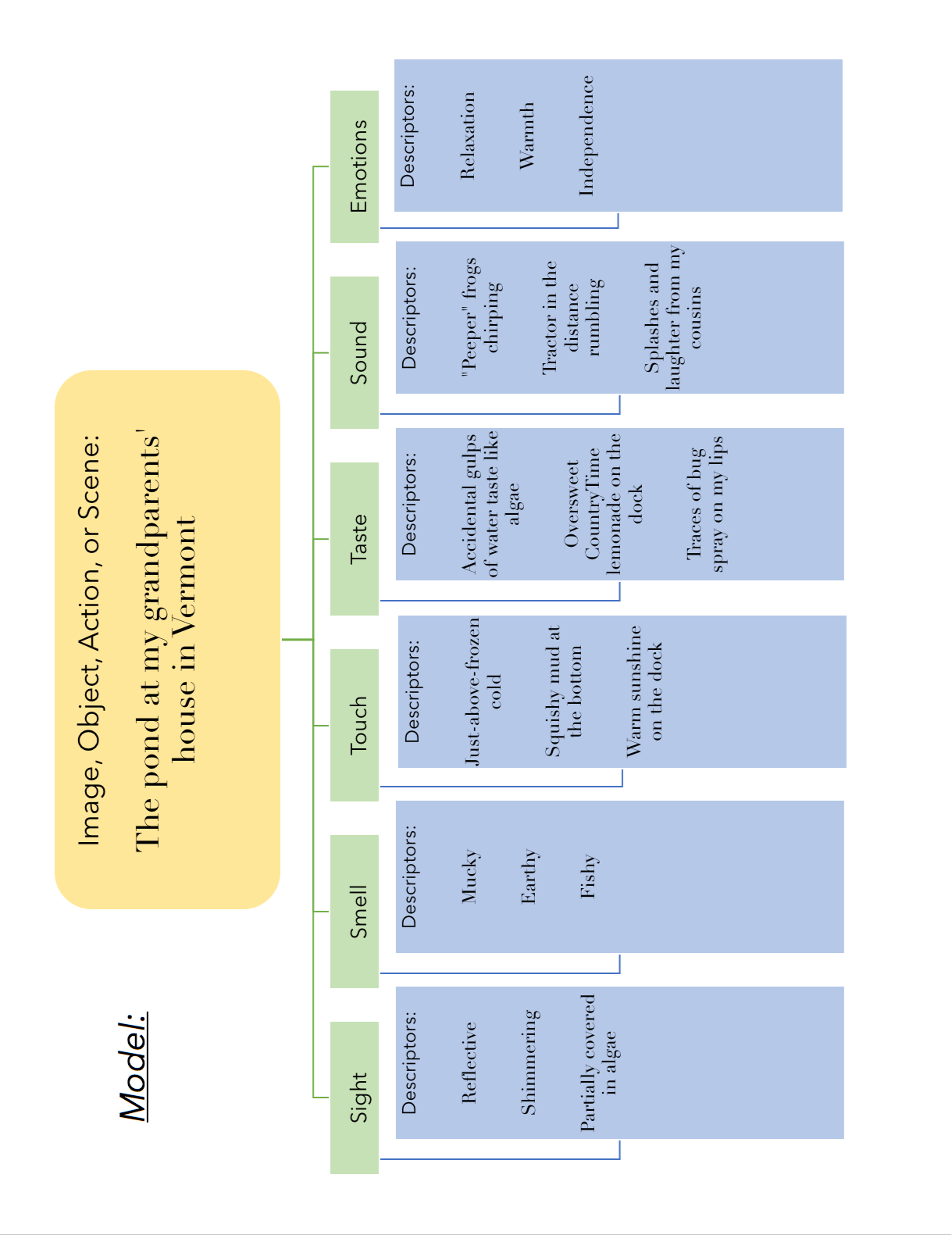

This exercise encourages you to experiment with thick description by focusing on one element of your writing in expansive detail. Read the directions below, then write your responses as an outline on a separate piece of paper.

1. Identify one image, object, action, or scene that you want to expand in your story. Name this element in the big, yellow bubble.

2. Develop at least three describing words for your element, considering each sense independently, as well as emotional associations. Focus on particularities. (Adjectives will come most easily, but remember that you can use any part of speech.)

3. Then, on the next page, create at least two descriptions using figurative language (metaphor, simile, personification, onomatopoeia, hyperbole, etc.) for your element, considering each sense independently, as well as emotional associations. Focus on particularities.

4. Finally, reflect on the different ideas you came up with.

- Which descriptions surprised you? Which descriptions are accurate but unanticipated?

- Where might you weave these descriptions in to your current project?

- How will you balance description with other rhetorical modes, like narration, argumentation, or analysis?

5. Repeat this exercise as desired or as instructed, choosing a different focus element to begin with.

6. Choose your favorite descriptors and incorporate them into your writing.

If you’re struggling to get started, check out the example on the pages following the blank organizer.

- There is a school of writing based on this practice, termed остранение by Viktor Shklovsky, commonly translated into English as “Art as Technique.” 1925. Literary Theory: An Anthology, 2nd ed. ↵

- (Athenaeum Press: Boston, 1903), pp. 85-86. ↵

- 3rd edition (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2014), p. 59. ↵

- qtd. in Joseph G. Ponterotto's "Brief Note on the Origins, Evolution, and Meaning of the Qualitative Research Concept 'Thick Description,'" The Qualitative Report (Vol. 1 No. 3) (Sept. 2006), p. 540. ↵