Rhetoric, as the previous chapters have discussed, is the way that authors use and manipulate language in order convey a message to an audience. Once we understand the rhetorical situation out of which a text is created, we can look at how all of those contextual elements shape the author’s creation of the text.

Whereas the previous chapters focus primarily on the rhetorical situation, the next few chapters focus on the classical appeals (or proofs), which are ways to classify authors’ intellectual, moral, and emotional approaches to getting the audience to have the reaction that the author hopes for. These appeals allow writers to communicate more or less persuasively with the audience.

Rhetorical appeals include ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos. These are classical Greek terms, dating back to Aristotle, who is traditionally seen as the father of rhetoric. To be rhetorically effective (and thus persuasive), an author must engage the audience in a variety of compelling ways, which involves carefully choosing how to craft his or her argument so that the outcome, audience agreement with the argument or point, is achieved.

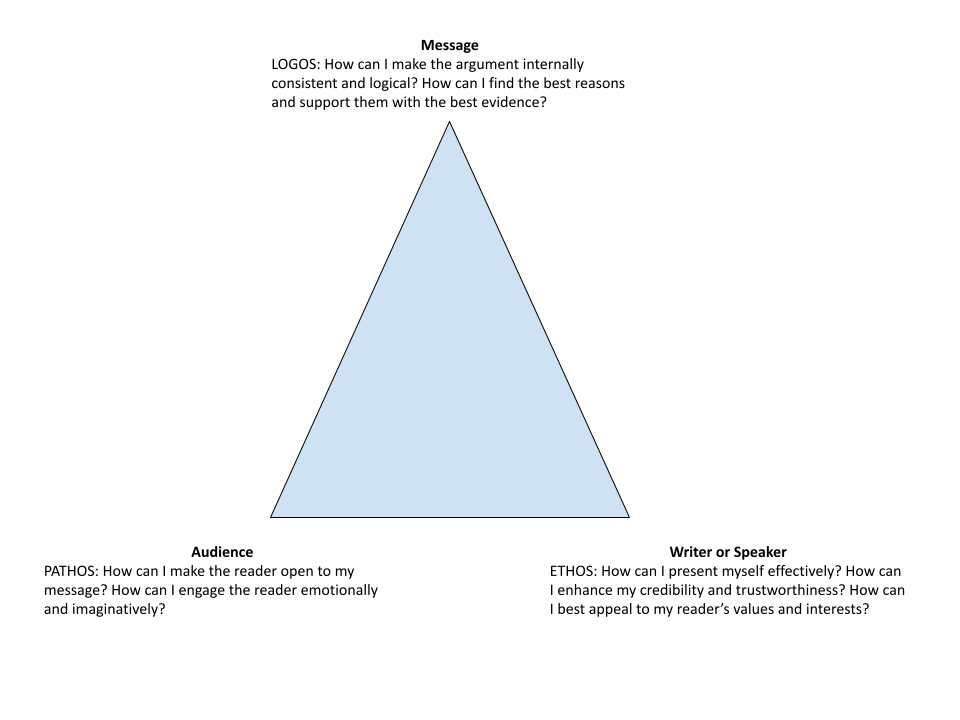

As a previous chapters explained, the Rhetorical Situation can be visualized as triangulating relating three main elements: Writer, Subject (or Message), and Audience. Three of the Rhetorical Appeals (logos, pathos, and ethos) can be mapped onto that triangle in the following way:

Logos, pathos, and ethos can be represented as distinct corners of a triangle, but it’s important to emphasize the sameness and interconnectedness of that triangle. Just as the message, audience, and writer all contribute to the final product, the rhetorical appeals are mutually reinforcing and intertwined. In the chapter, “Moving Your Audience: Ethos, Pathos, and Kairos,” John D. Ramage, et al’s Writing Arguments shows how the following logical proof can be communicated in different ways:

Claim: People should adopt a vegetarian diet.

Reason: Because doing so will help prevent cruelty to animals caused by factory farming.

Here are the various examples they provide:

- People should adopt a vegetarian diet because doing so will help prevent the cruelty to animals caused by factory farming.

- If you are planning to eat chicken tonight, please consider how much that chicken suffered so that you could have a tender and juicy meal. Commercial growers cram the chickens so tightly together into cages that they never walk on their own legs, see sunshine, or flap their wings. In fact, their beaks must be cut off to keep them from pecking each other’s eyes out. One way to prevent such suffering is for more and more people to become vegetarians.

- People who eat meat are no better than sadists who torture other sentient creatures to enhance their own pleasure. Unless you enjoy sadistic tyranny over others, you have only one choice: become a vegetarian.

- People committed to justice might consider the extent to which our love of eating meat requires the agony of animals. A visit to a modern chicken factory—where chickens live their entire lives in tiny, darkened coops without room to spread their wings—might raise doubts about our right to inflict such suffering on sentient creatures. Indeed, such a visit might persuade us that vegetarianism is a more just alternative.

The coldest, most straightforward formulation of the argument is found in version 1. Argument 2 sounds more informal, in part because it uses the second person “you,” but also because it pleads with the reader by appealing to their imagination. Concrete imagery is one type way to practice pathos. Argument 3 uses the emotionally charged language of pathos again, but now enhanced by a kind of moral superiority over the reader. The phrase, “People who eat meat are no better than,” splits the audience into those whose morals align with the writer and those who don’t. By drawing attention to the writer’s character, it draws on ethos. However, as Ramage, et al point out, most readers find Argument 3 the most off-putting. It’s a poor, unpersuasive use of ethos.

Argument 4 practices ethos better, especially when communicating to an audience that expects civil conversation. Argument 4 also uses ethos by appealing to the reader’s values (“committed to justice”). Finally, by briefly mentioning at “visit to a modern chicken factory,” this version of the argument also taps into the reader’s imagination, a type of pathos.

The persuasiveness of Argument 4 shows how logos, pathos, and ethos aren’t easily separated into discrete elements that a writer drops in one sentence at a time. The same sentence or passage can practice logos, pathos, and ethos all at once. When going back to analyze the how the passage works, a critical reader can use the individual rhetorical terms to analyze its persuasiveness.

Logic. Reason. Rationality. Logos is brainy and intellectual, cool, calm, collected, objective.

When an author relies on logos, it means that he or she is using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. An author can appeal to an audience’s intellect by using information that can be fact checked (using multiple sources) and thorough explanations to support key points. Additionally, providing a solid and non-biased explanation of one’s argument is a great way for an author to invoke logos.

For example, if I were trying to convince my students to complete their homework, I might explain that I understand everyone is busy and they have other classes (non-biased), but the homework will help them get a better grade on their test (explanation). I could add to this explanation by providing statistics showing the number of students who failed and didn’t complete their homework versus the number of students who passed and did complete their homework (factual evidence).

Logical appeals rest on rational modes of thinking, such as

- Comparison – a comparison between one thing (with regard to your topic) and another, similar thing to help support your claim. It is important that the comparison is fair and valid – the things being compared must share significant traits of similarity.

- Cause/effect thinking – you argue that X has caused Y, or that X is likely to cause Y to help support your claim. Be careful with the latter – it can be difficult to predict that something “will” happen in the future.

- Deductive reasoning – starting with a broad, general claim/example and using it to support a more specific point or claim

- Inductive reasoning – using several specific examples or cases to make a broad generalization

- Exemplification – use of many examples or a variety of evidence to support a single point

- Elaboration – moving beyond just including a fact, but explaining the significance or relevance of that fact

- Coherent thought – maintaining a well organized line of reasoning; not repeating ideas or jumping around

When an author relies on pathos, it means that he or she is trying to tap into the audience’s emotions to get them to agree with the author’s claim. An author using pathetic appeals wants the audience to feel something: anger, pride, joy, rage, or happiness. For example, many of us have seen the ASPCA commercials that use photographs of injured puppies, or sad-looking kittens, and slow, depressing music to emotionally persuade their audience to donate money.

Pathos-based rhetorical strategies are any strategies that get the audience to “open up” to the topic, the argument, or to the author. Emotions can make us vulnerable, and an author can use this vulnerability to get the audience to believe that his or her argument is a compelling one.

Pathetic appeals might include

- Expressive descriptions of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel or experience those events

- Vivid imagery of people, places or events that help the reader to feel like he or she is seeing those events

- Sharing personal stories that make the reader feel a connection to, or empathy for, the person being described

- Using emotion-laden vocabulary as a way to put the reader into that specific emotional mindset (what is the author trying to make the audience feel? and how is he or she doing that?)

- Using any information that will evoke an emotional response from the audience. This could involve making the audience feel empathy or disgust for the person/group/event being discussed, or perhaps connection to or rejection of the person/group/event being discussed.

When reading a text, try to locate when the author is trying to convince the reader using emotions because, if used to excess, pathetic appeals can indicate a lack of substance or emotional manipulation of the audience. See the links below about fallacious pathos for more information.

Ethical appeals have two facets: audience values and authorial credibility/character.

On the one hand, when an author makes an ethical appeal, he or she is attempting to tap into the values or ideologies that the audience holds, for example, patriotism, tradition, justice, equality, dignity for all humankind, self preservation, or other specific social, religious or philosophical values (Christian values, socialism, capitalism, feminism, etc.). These values can sometimes feel very close to emotions, but they are felt on a social level rather than only on a personal level. When an author evokes the values that the audience cares about as a way to justify or support his or her argument, we classify that as ethos. The audience will feel that the author is making an argument that is “right” (in the sense of moral “right”-ness, i.e., “My argument rests upon that values that matter to you. Therefore, you should accept my argument”). This first part of the definition of ethos, then, is focused on the audience’s values.

On the other hand, this sense of referencing what is “right” in an ethical appeal connects to the other sense of ethos: the author. Ethos that is centered on the author revolves around two concepts: the credibility of the author and his or her character.

Credibility of the speaker/author is determined by his or her knowledge and expertise in the subject at hand. For example, if you are learning about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, would you rather learn from a professor of physics or a cousin who took two science classes in high school thirty years ago? It is fair to say that, in general, the professor of physics would have more credibility to discuss the topic of physics. To establish his or her credibility, an author may draw attention to who he or she is or what kinds of experience he or she has with the topic being discussed as an ethical appeal (i.e., “Because I have experience with this topic – and I know my stuff! – you should trust what I am saying about this topic”). Some authors do not have to establish their credibility because the audience already knows who they are and that they are credible.

Character is another aspect of ethos, and it is different from credibility because it involves personal history and even personality traits. A person can be credible but lack character or vice versa. For example, in politics, sometimes the most experienced candidates – those who might be the most credible candidates – fail to win elections because voters do not accept their character. Politicians take pains to shape their character as leaders who have the interests of the voters at heart. The candidate who successfully proves to the voters (the audience) that he or she has the type of character that they can trust is more likely to win.

Thus, ethos comes down to trust. How can the author get the audience to trust him or her so that they will accept his or her argument? How can the the author make him or herself appear as a credible speaker who embodies the character traits that the audience values?

In building ethical appeals, we see authors

- Referring either directly or indirectly to the values that matter to the intended audience (so that the audience will trust the speaker)

- Using language, phrasing, imagery, or other writing styles common to people who hold those values, thereby “talking the talk” of people with those values (again, so that the audience is inclined to trust the speaker)

- Referring to their experience and/or authority with the topic (and therefore demonstrating their credibility)

- Referring to their own character, or making an effort to build their character in the text

When reading, you should always think about the author’s credibility regarding the subject as well as his or her character. Here is an example of a rhetorical move that connects with ethos: when reading an article about abortion, the author mentions that she has had an abortion. That is an example of an ethical move because the author is creating credibility via anecdotal evidence and first person narrative. In a rhetorical analysis project, it would be up to you, the analyzer, to point out this move and associate it with a rhetorical strategy.

Above, we defined and described what logos, pathos, and ethos are and why authors may use those strategies. Sometimes, using a combination of logical, pathetic, and ethical appeals leads to a sound, balanced, and persuasive argument. It is important to understand, though, that using rhetorical appeals does not always lead to a sound, balanced argument.

In fact, any of the appeals could be misused or overused. When that happens, arguments can be weakened.

To see how authors can overuse emotional appeals and turn-off their target audience, visit the following link from WritingCommons.org: Fallacious Pathos.

To see how ethos can be misused or used in a manner that may be misleading, visit the following link to WritingCommons.org: Fallacious Ethos.

Literally translated, kairos means the “supreme moment.” In this case, it refers to appropriate timing, meaning when the writer presents certain parts of her argument as well as the overall timing of the subject matter itself. While not technically part of the Rhetorical Triangle, it is still an important principle for constructing an effective argument. If the writer fails to establish a strong kairotic appeal, then the audience may become polarized, hostile, or may simply just lose interest.

If appropriate timing is not taken into consideration and a writer introduces a sensitive or important point too early or too late in a text, the impact of that point could be lost on the audience. For example, if the writer’s audience is strongly opposed to her view, and she begins the argument with a forceful thesis of why she is right and the opposition is wrong, how do you think that audience might respond?

In this instance, the writer may have just lost the ability to make any further appeals to her audience in two ways: first, by polarizing them, and second, by possibly elevating what was at first merely strong opposition to what would now be hostile opposition. A polarized or hostile audience will not be inclined to listen to the writer’s argument with an open mind or even to listen at all. On the other hand, the writer could have established a stronger appeal to Kairos by building up to that forceful thesis, maybe by providing some neutral points such as background information or by addressing some of the opposition’s views, rather than leading with why she is right and the audience is wrong.

Additionally, if a writer covers a topic or puts forth an argument about a subject that is currently a non-issue or has no relevance for the audience, then the audience will fail to engage because whatever the writer’s message happens to be, it won’t matter to anyone. For example, if a writer were to put forth the argument that women in the United States should have the right to vote, no one would care; that is a non-issue because women in the United States already have that right.

When evaluating a writer’s kairotic appeal, ask the following questions:

- Where does the writer establish her thesis of the argument in the text? Is it near the beginning, the middle, or the end? Is this placement of the thesis effective? Why or why not?

- Where in the text does the writer provide her strongest points of evidence? Does that location provide the most impact for those points?

- Is the issue that the writer raises relevant at this time, or is it something no one really cares about anymore or needs to know about anymore?

Exercise 4: Analyzing Kairos

In this exercise, you will analyze a visual representation of the appeal to Kairos. On the 26th of February 2015, a photo of a dress was posted to Twitter along with a question as to whether people thought it was one combination of colors versus another. Internet chaos ensued on social media because while some people saw the dress as black and blue, others saw it as white and gold. As the color debate surrounding the dress raged on, an ad agency in South Africa saw an opportunity to raise awareness about a far more serious subject: domestic abuse.

Step 1: Read this article (https://tinyurl.com/yctl8o5g) from CNN about how and why the photo of the dress went viral so that you will be better informed for the next step in this exercise:

Step 2: Watch the video (https://youtu.be/SLv0ZRPssTI, transcript here) from CNN that explains how, in partnership with The Salvation Army, the South African marketing agency created an ad that went viral.

Step 3: After watching the video, answer the following questions:

- Once the photo of the dress went viral, approximately how long after did the Salvation Army’s ad appear? Look at the dates on both the article and the video to get an idea of a time frame.

- How does the ad take advantage of the publicity surrounding the dress?

- Would the ad’s overall effectiveness change if it had come out later than it did?

- How late would have been too late to make an impact? Why?

Parts of this chapter are from Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel’s

A Guide to Rhetoric, “

Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos Defined,” CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0; “The Appeal to Kairos” is from

Let’s Get Writing!, “

Chapter 2 – Rhetorical Analysis,” by Elizabeth Browning.