26 Reading Rhetorically, or How to Read Like a Writer

Liza Long

By Liza Long

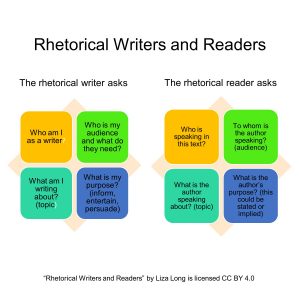

As with any skill, writing rhetorically begins with reading rhetorically. But what exactly do we mean by rhetoric? Reading rhetorically is really just reading like a writer. When you read rhetorically, you are joining the conversation with the writer as an active, engaged, and critical participant. This type of reading is not a strategy like active reading or a formula that we can apply to every text. Instead, reading rhetorically is a habit of mind that life-long learners work to adopt. This habit of mind will help you engage with texts–from social media posts to peer-reviewed journal articles and everything in between–instead of passively consuming them. Rhetorical reading will make you a better thinker and a better writer.

Interrogating the Rhetor/Author

Rhetorical reading begins with asking questions about the rhetor, or the speaker. Essentially, reading rhetorically is reading critically, starting with a critical interrogation of the text’s author, where we ask ourselves a series of questions about the writer, their worldview, and their intentions.

In the approach below, I have used the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s elements of argument to help us think about the rhetor, or author of a text. These same elements of argument (also called Classical Argument) are also used by writers, as we will see in later chapters.

In the approach below, I have used the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s elements of argument to help us think about the rhetor, or author of a text. These same elements of argument (also called Classical Argument) are also used by writers, as we will see in later chapters.

Here are some questions we can ask about the rhetor:

Ethos (Character):

- Who is the author?

- Why is the author qualified to write about this topic? Does the author have lived experience? Are they an expert?

- How does the author establish themselves as credible to readers? Does the author seem credible to me? Why or why not?

Pathos (Emotion):

- What relationship does the author have with their intended audience?

- Who is the intended audience, and am I part of that group? Why do I think that I am or am not part of the intended audience?

- What is the author’s overall tone? (humorous, emotional, logical, etc.)

- How does the author engage the reader? Do I feel engaged as I read? Why or why not?

- How do I feel as I read this text? Do I agree with the author, disagree, or both? What emotions, if any, does this text bring up for me? How does the author invoke these emotions?

Logos (Reason)

- What question(s) or topic(s) does this text address?

- Why are these questions or topics important? (so what? Who cares?)

- What group of people cares about this topic? A community? An organization? A demographic group? (example, Boomers or Zoomers)

- What types of reason or evidence does the author use?

- Are these reasons and evidence credible? Why or why not?

Let’s combine the questions we asked above into a checklist that you can use as you read a text:

- So what? Who cares? What questions does the text address? Why are these questions important? What types of people or communities/organizations care about these questions?

- Who is this text written for? Who is the intended audience? Am I part of this audience or an outsider?

- How does the author support their thesis? What types of evidence are used? Personal experience? Facts and statistics? Original observations, interviews, or research?

- Do I find this argument convincing? Whose views and counterarguments are omitted from the text? Is the counterargument or counterevidence addressed or ignored?

- How does the author hook the intended reader’s interest and keep the reader reading? Does this hook work for me? For example, the author may use emotion (pathos), authority or character (ethos), or reasons and evidence (logos) to introduce the argument.

- How does the author make themselves seem credible to the intended audience? Is the author credible for me? Are the author’s sources reliable?

- Are this author’s basic values, beliefs, and assumptions similar to or different from my own? Do the author and I share the same worldview or do we have different perspectives?

- How do I respond to this text? What are my initial reactions? Do I agree, disagree, or both? Has the text changed my thinking or made me reconsider my position in any way?

- How will I be able to use what I have learned from the text in my own writing? Think about the type of writing assignment where this source might be useful, and how you would use it.

Now, let’s practice. Here’s a passage from Ta Nehisi Coates’s National Book Award winning book Between the World and Me, written in the form of a letter from the African American public intellectual and author to his 15-year-old son. As you read the following passage, keep the questions above in mind. You may want to jot down notes and use active reading strategies.

Americans believe in the reality of “race” as a defined, indubitable feature of the natural world. Racism—the need to ascribe bone-deep features to people and then humiliate, reduce, and destroy them—inevitably follows from this inalterable condition. In this way, racism is rendered as the innocent daughter of Mother Nature, and one is left to deplore the Middle Passage or the Trail of Tears the way one deplores an earthquake, a tornado, or any other phenomenon that can be cast as beyond the handiwork of men.

But race is the child of racism, not the father. And the process of naming “the people” has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy. Difference in hue and hair is old. But the belief in the preeminence of hue and hair, the notion that these factors can correctly organize a society and that they signify deeper attributes, which are indelible—this is the new idea at the heart of this new people who have been brought up hopelessly, tragically, deceitfully, to believe that they are white.

These new people are, like us, a modern invention. But unlike us, their new name has no real meaning divorced from the machinery of criminal power. The new people were something else before they were white—Catholic, Corsican, Welsh, Mennonite, Jewish—and if all our national hopes have any fulfillment, then they will have to be something else again. Perhaps they will truly become American and create a nobler basis for their myths. I cannot call it. As for now, it must be said that the process of washing the disparate tribes white, the elevation of the belief in being white, was not achieved through wine tastings and ice cream socials, but rather through the pillaging of life, liberty, labor, and land; through the flaying of backs; the chaining of limbs; the strangling of dissidents; the destruction of families; the rape of mothers; the sale of children; and various other acts meant, first and foremost, to deny you and me the right to secure and govern our own bodies.

Ta Nehisi Coates, excerpt from Between the World and Me, Penguin Randomhouse, 2015, https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/220290/between-the-world-and-me-by-ta-nehisi-coates/9780812993547/excerpt

Interrogating the Reader (Yourself)

Think about the types of arguments we see on the Internet today. Are people reading each other’s tweets and posts rhetorically? Are they responding as if they are using rhetorical skills to listen? Or are they using rhetorical skills to win?