169 What Is “Academic” Writing?

Lennie Irvin

Introduction: The Academic Writing Task

As a new college student, you may have a lot of anxiety and questions about the writing you’ll do in college.* That word “academic,” especially, may turn your stomach or turn your nose. However, with this first year composition class, you begin one of the only classes in your entire college career where you will focus on learning to write. Given the importance of writing as a communication skill, I urge you to consider this class as a gift and make the most of it. But writing is hard, and writing in college may resemble playing a familiar game by completely new rules (that often are unstated). This chapter is designed to introduce you to what academic writing is like, and hopefully ease your transition as you face these daunting writing challenges.

So here’s the secret. Your success with academic writing depends upon how well you understand what you are doing as you write and then how you approach the writing task. Early research done on college writers discovered that whether students produced a successful piece of writing depended largely upon their representation of the writing task. The writers’ mental model for picturing their task made a huge difference. Most people as they start college have wildly strange ideas about what they are doing when they write an essay, or worse—they have no clear idea at all. I freely admit my own past as a clueless freshman writer, and it’s out of this sympathy as well as twenty years of teaching college writing that I hope to provide you with something useful. So grab a cup of coffee or a diet coke, find a comfortable chair with good light, and let’s explore together this activity of academic writing you’ll be asked to do in college. We will start by clearing up some of those wild misconceptions people often arrive at college possessing. Then we will dig more deeply into the components of the academic writing situation and nature of the writing task.

Myths about Writing

Though I don’t imagine an episode of MythBusters will be based on the misconceptions about writing we are about to look at, you’d still be surprised at some of the things people will believe about writing. You may find lurking within you viral elements of these myths—all of these lead to problems in writing.

Myth #1: The “Paint by Numbers” myth

Some writers believe they must perform certain steps in a particular order to write “correctly.” Rather than being a lock-step linear process, writing is “recursive.” That means we cycle through and repeat the various activities of the writing process many times as we write.

Myth #2: Writers only start writing when they have everything figured out

Writing is not like sending a fax! Writers figure out much of what they want to write as they write it. Rather than waiting, get some writing on the page—even with gaps or problems. You can come back to patch up rough spots.

Myth #3: Perfect first drafts

We put unrealistic expectations on early drafts, either by focusing too much on the impossible task of making them perfect (which can put a cap on the development of our ideas), or by making too little effort because we don’t care or know about their inevitable problems. Nobody writes perfect first drafts; polished writing takes lots of revision.

Myth #4: Some got it; I don’t—the genius fallacy

When you see your writing ability as something fixed or out of your control (as if it were in your genetic code), then you won’t believe you can improve as a writer and are likely not to make any efforts in that direction. With effort and study, though, you can improve as a writer. I promise.

Myth #5: Good grammar is good writing

When people say “I can’t write,” what they often mean is they have problems with grammatical correctness. Writing, however, is about more than just grammatical correctness. Good writing is a matter of achieving your desired effect upon an intended audience. Plus, as we saw in myth #3, no one writes perfect first drafts.

Myth #6: The Five Paragraph Essay

Some people say to avoid it at all costs, while others believe no other way to write exists. With an introduction, three supporting paragraphs, and a conclusion, the five paragraph essay is a format you should know, but one which you will outgrow. You’ll have to gauge the particular writing assignment to see whether and how this format is useful for you.

Myth #7: Never use “I”

Adopting this formal stance of objectivity implies a distrust (almost fear) of informality and often leads to artificial, puffed-up prose. Although some writing situations will call on you to avoid using “I” (for example, a lab report), much college writing can be done in a middle, semi-formal style where it is ok to use “I.”

The Academic Writing Situation

Now that we’ve dispelled some of the common myths that many writers have as they enter a college classroom, let’s take a moment to think about the academic writing situation. The biggest problem I see in freshman writers is a poor sense of the writing situation in general. To illustrate this problem, let’s look at the difference between speaking and writing.

When we speak, we inhabit the communication situation bodily in three dimensions, but in writing we are confined within the twodimensional setting of the flat page (though writing for the web—or multimodal writing—is changing all that). Writing resembles having a blindfold over our eyes and our hands tied behind our backs: we can’t see exactly whom we’re talking to or where we are. Separated from our audience in place and time, we imaginatively have to create this context. Our words on the page are silent, so we must use punctuation and word choice to communicate our tone. We also can’t see our audience to gauge how our communication is being received or if there will be some kind of response. It’s the same space we share right now as you read this essay. Novice writers often write as if they were mumbling to themselves in the corner with no sense that their writing will be read by a reader or any sense of the context within which their communication will be received.

What’s the moral here? Developing your “writer’s sense” about communicating within the writing situation is the most important thing you should learn in freshman composition.

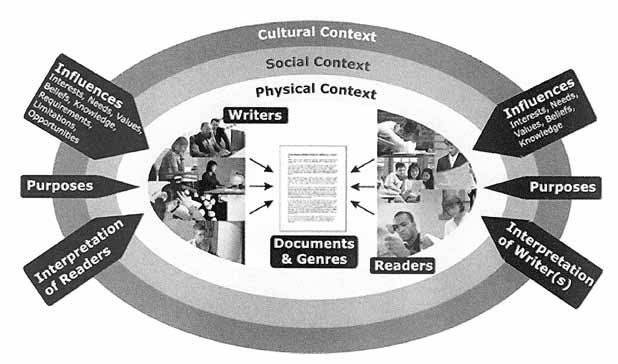

Figure 1, depicting the writing situation, presents the best image I know of describing all the complexities involved in the writing situation.

Looking More Closely at the “Academic Writing” Situation

Writing in college is a fairly specialized writing situation, and it has developed its own codes and conventions that you need to have a keen awareness of if you are going to write successfully in college. Let’s break down the writing situation in college:

| Who’s your audience? | Primarily the professor and possibly your classmates (though you may be asked to include a secondary outside audience). |

| What’s the occasion or context? | An assignment given by the teacher within a learning context and designed to have you learn and demonstrate your learning. |

| What’s your message? | It will be your learning or the interpretation gained from your study of the subject matter. |

| What’s your purpose? | To show your learning and get a good grade (or to accomplish the goals of the writing assignment). |

| What documents/ genres are used? | The essay is the most frequent type of document used. |

So far, this list looks like nothing new. You’ve been writing in school toward teachers for years. What’s different in college? Lee Ann Carroll, a professor at Pepperdine University, performed a study of student writing in college and had this description of the kind of writing you will be doing in college:

What are usually called ‘writing assignments’ in college might more accurately be called ‘literacy tasks’ because they require much more than the ability to construct correct sentences or compose neatly organized paragraphs with topic sentences. . . . Projects calling for high levels of critical literacy in college typically require knowledge of research skills, ability to read complex texts, understanding of key disciplinary concepts, and strategies for synthesizing, analyzing, and responding critically to new information, usually within a limited time frame. (3–4)

Academic writing is always a form of evaluation that asks you to demonstrate knowledge and show proficiency with certain disciplinary skills of thinking, interpreting, and presenting. Writing the paper is never “just” the writing part. To be successful in this kind of writing, you must be completely aware of what the professor expects you to do and accomplish with that particular writing task. For a moment, let’s explore more deeply the elements of this college writing “literacy task.”

Knowledge of Research Skills

Perhaps up to now research has meant going straight to Google and Wikipedia, but college will require you to search for and find more in-depth information. You’ll need to know how to find information in the library, especially what is available from online databases which contain scholarly articles. Researching is also a process, so you’ll need to learn how to focus and direct a research project and how to keep track of all your source information. Realize that researching represents a crucial component of most all college writing assignments, and you will need to devote lots of work to this researching.

The Ability to Read Complex Texts

Whereas your previous writing in school might have come generally from your experience, college writing typically asks you to write on unfamiliar topics. Whether you’re reading your textbook, a short story, or scholarly articles from research, your ability to write well will be based upon the quality of your reading. In addition to the labor of close reading, you’ll need to think critically as you read. That means separating fact from opinion, recognizing biases and assumptions, and making inferences. Inferences are how we as readers connect the dots: an inference is a belief (or statement) about something unknown made on the basis of something known. You smell smoke; you infer fire. They are conclusions or interpretations that we arrive at based upon the known factors we discover from our reading. When we, then, write to argue for these interpretations, our job becomes to get our readers to make the same inferences we have made.

The Understanding of Key Disciplinary Concepts

Each discipline whether it is English, Psychology, or History has its own key concepts and language for describing these important ways of understanding the world. Don’t fool yourself that your professors’ writing assignments are asking for your opinion on the topic from just your experience. They want to see you apply and use these concepts in your writing. Though different from a multiple-choice exam, writing similarly requires you to demonstrate your learning. So whatever writing assignment you receive, inspect it closely for what concepts it asks you to bring into your writing.

Strategies for Synthesizing, Analyzing, and Responding Critically to New Information

You need to develop the skill of a seasoned traveler who can be dropped in any city around the world and get by. Each writing assignment asks you to navigate through a new terrain of information, so you must develop ways for grasping new subject matter in order, then, to use it in your writing. We have already seen the importance of reading and research for these literacy tasks, but beyond laying the information out before you, you will need to learn ways of sorting and finding meaningful patterns in this information.

In College, Everything’s an Argument: A Guide for Decoding College Writing Assignments

Let’s restate this complex “literacy task” you’ll be asked repeatedly to do in your writing assignments. Typically, you’ll be required to write an “essay” based upon your analysis of some reading(s). In this essay you’ll need to present an argument where you make a claim (i.e. present a “thesis”) and support that claim with good reasons that have adequate and appropriate evidence to back them up. The dynamic of this argumentative task often confuses first year writers, so let’s examine it more closely.

Academic Writing Is an Argument

To start, let’s focus on argument. What does it mean to present an “argument” in college writing? Rather than a shouting match between two disagreeing sides, argument instead means a carefully arranged and supported presentation of a viewpoint. Its purpose is not so much to win the argument as to earn your audience’s consideration (and even approval) of your perspective. It resembles a conversation between two people who may not hold the same opinions, but they both desire a better understanding of the subject matter under discussion. My favorite analogy, however, to describe the nature of this argumentative stance in college writing is the courtroom. In this scenario, you are like a lawyer making a case at trial that the defendant is not guilty, and your readers are like the jury who will decide if the defendant is guilty or not guilty. This jury (your readers) won’t just take your word that he’s innocent; instead, you must convince them by presenting evidence that proves he is not guilty. Stating your opinion is not enough—you have to back it up too. I like this courtroom analogy for capturing two importance things about academic argument: 1) the value of an organized presentation of your “case,” and 2) the crucial element of strong evidence.

Academic Writing Is an Analysis

We now turn our attention to the actual writing assignment and that confusing word “analyze.” Your first job when you get a writing assignment is to figure out what the professor expects. This assignment may be explicit in its expectations, but often built into the wording of the most defined writing assignments are implicit expectations that you might not recognize. First, we can say that unless your professor specifically asks you to summarize, you won’t write a summary. Let me say that again: don’t write a summary unless directly asked to. But what, then, does the professor want? We have already picked out a few of these expectations: You can count on the instructor expecting you to read closely, research adequately, and write an argument where you will demonstrate your ability to apply and use important concepts you have been studying. But the writing task also implies that your essay will be the result of an analysis. At times, the writing assignment may even explicitly say to write an analysis, but often this element of the task remains unstated.

So what does it mean to analyze? One way to think of an analysis is that it asks you to seek How and Why questions much more than What questions. An analysis involves doing three things:

- Engage in an open inquiry where the answer is not known at first (and where you leave yourself open to multiple suggestions)

- Identify meaningful parts of the subject

- Examine these separate parts and determine how they relate to each other

An analysis breaks a subject apart to study it closely, and from this inspection, ideas for writing emerge. When writing assignments call on you to analyze, they require you to identify the parts of the subject (parts of an ad, parts of a short story, parts of Hamlet’s character), and then show how these parts fit or don’t fit together to create some larger effect or meaning. Your interpretation of how these parts fit together constitutes your claim or thesis, and the task of your essay is then to present an argument defending your interpretation as a valid or plausible one to make. My biggest bit of advice about analysis is not to do it all in your head. Analysis works best when you put all the cards on the table, so to speak. Identify and isolate the parts of your analysis, and record important features and characteristics of each one. As patterns emerge, you sort and connect these parts in meaningful ways. For me, I have always had to do this recording and thinking on scratch pieces of paper. Just as critical reading forms a crucial element of the literacy task of a college writing assignment, so too does this analysis process. It’s built in.

Three Common Types of College Writing Assignments

We have been decoding the expectations of the academic writing task so far, and I want to turn now to examine the types of assignments you might receive. From my experience, you are likely to get three kinds of writing assignments based upon the instructor’s degree of direction for the assignment. We’ll take a brief look at each kind of academic writing task.

The Closed Writing Assignment

- Is Creon a character to admire or condemn?

- Does your advertisement employ techniques of propaganda, and if so what kind?

- Was the South justified in seceding from the Union?

- In your opinion, do you believe Hamlet was truly mad?

These kinds of writing assignments present you with two counter claims and ask you to determine from your own analysis the more valid claim. They resemble yes-no questions. These topics define the claim for you, so the major task of the writing assignment then is working out the support for the claim. They resemble a math problem in which the teacher has given you the answer and now wants you to “show your work” in arriving at that answer.

Be careful with these writing assignments, however, because often these topics don’t have a simple yes/no, either/or answer (despite the nature of the essay question). A close analysis of the subject matter often reveals nuances and ambiguities within the question that your eventual claim should reflect. Perhaps a claim such as, “In my opinion, Hamlet was mad” might work, but I urge you to avoid such a simplistic thesis. This thesis would be better: “I believe Hamlet’s unhinged mind borders on insanity but doesn’t quite reach it.”

The Semi-Open Writing Assignment

- Discuss the role of law in Antigone.

- Explain the relationship between character and fate in Hamlet.

- Compare and contrast the use of setting in two short stories.

- Show how the Fugitive Slave Act influenced the Abolitionist Movement.

Although these topics chart out a subject matter for you to write upon, they don’t offer up claims you can easily use in your paper. It would be a misstep to offer up claims such as, “Law plays a role in Antigone” or “In Hamlet we can see a relationship between character and fate.” Such statements express the obvious and what the topic takes for granted. The question, for example, is not whether law plays a role in Antigone, but rather what sort of role law plays. What is the nature of this role? What influences does it have on the characters or actions or theme? This kind of writing assignment resembles a kind of archeological dig. The teacher cordons off an area, hands you a shovel, and says dig here and see what you find.

Be sure to avoid summary and mere explanation in this kind of assignment. Despite using key words in the assignment such as “explain,” “illustrate,” analyze,” “discuss,” or “show how,” these topics still ask you to make an argument. Implicit in the topic is the expectation that you will analyze the reading and arrive at some insights into patterns and relationships about the subject. Your eventual paper, then, needs to present what you found from this analysis—the treasure you found from your digging. Determining your own claim represents the biggest challenge for this type of writing assignment.

The Open Writing Assignment

- Analyze the role of a character in Dante’s The Inferno.

- What does it mean to be an “American” in the 21st Century?

- Analyze the influence of slavery upon one cause of the Civil War.

- Compare and contrast two themes within Pride and Prejudice.

These kinds of writing assignments require you to decide both your writing topic and you claim (or thesis). Which character in the Inferno will I pick to analyze? What two themes in Pride and Prejudice will I choose to write about? Many students struggle with these types of assignments because they have to understand their subject matter well before they can intelligently choose a topic. For instance, you need a good familiarity with the characters in The Inferno before you can pick one. You have to have a solid understanding defining elements of American identity as well as 21st century culture before you can begin to connect them. This kind of writing assignment resembles riding a bike without the training wheels on. It says, “You decide what to write about.” The biggest decision, then, becomes selecting your topic and limiting it to a manageable size.

Picking and Limiting a Writing Topic

Let’s talk about both of these challenges: picking a topic and limiting it. Remember how I said these kinds of essay topics expect you to choose what to write about from a solid understanding of your subject? As you read and review your subject matter, look for things that interest you. Look for gaps, puzzling items, things that confuse you, or connections you see. Something in this pile of rocks should stand out as a jewel: as being “do-able” and interesting. (You’ll write best when you write from both your head and your heart.) Whatever topic you choose, state it as a clear and interesting question. You may or may not state this essay question explicitly in the introduction of your paper (I actually recommend that you do), but it will provide direction for your paper and a focus for your claim since that claim will be your answer to this essay question. For example, if with the Dante topic you decided to write on Virgil, your essay question might be: “What is the role of Virgil toward the character of Dante in The Inferno?” The thesis statement, then, might be this: “Virgil’s predominant role as Dante’s guide through hell is as the voice of reason.” Crafting a solid essay question is well worth your time because it charts the territory of your essay and helps you declare a focused thesis statement.

Many students struggle with defining the right size for their writing project. They chart out an essay question that it would take a book to deal with adequately. You’ll know you have that kind of topic if you have already written over the required page length but only touched one quarter of the topics you planned to discuss. In this case, carve out one of those topics and make your whole paper about it. For instance, with our Dante example, perhaps you planned to discuss four places where Virgil’s role as the voice of reason is evident. Instead of discussing all four, focus your essay on just one place. So your revised thesis statement might be: “Close inspection of Cantos I and II reveal that Virgil serves predominantly as the voice of reason for Dante on his journey through hell.” A writing teacher I had in college said it this way: A well tended garden is better than a large one full of weeds. That means to limit your topic to a size you can handle and support well.

Three Characteristics of Academic Writing

I want to wrap up this section by sharing in broad terms what the expectations are behind an academic writing assignment. Chris Thaiss and Terry Zawacki conducted research at George Mason University where they asked professors from their university what they thought academic writing was and its standards. They came up with three characteristics:

- Clear evidence in writing that the writer(s) have been persistent, open-minded, and disciplined in study. (5)

- The dominance of reason over emotions or sensual perception. (5)

- An imagined reader who is coolly rational, reading for information, and intending to formulate a reasoned response. (7) Your professor wants to see these three things in your writing when they give you a writing assignment. They want to see in your writing the results of your efforts at the various literacy tasks we have been discussing: critical reading, research, and analysis. Beyond merely stating opinions, they also want to see an argument toward an intelligent audience where you provide good reasons to support your interpretations.

The Format of the Academic Essay

Your instructors will also expect you to deliver a paper that contains particular textual features. The following list contains the characteristics of what I have for years called the “critical essay.” Although I can’t claim they will be useful for all essays in college, I hope that these features will help you shape and accomplish successful college essays. Be aware that these characteristics are flexible and not a formula, and any particular assignment might ask for something different.

Characteristics of the Critical Essay

“Critical” here is not used in the sense of “to criticize” as in find fault with. Instead, “critical” is used in the same way “critical thinking” is used. A synonym might be “interpretive” or “analytical.”

- It is an argument, persuasion essay that in its broadest sense MAKES A POINT and SUPPORTS IT. (We have already discussed this argumentative nature of academic writing at length.)

- The point (“claim” or “thesis”) of a critical essay is interpretive in nature. That means the point is debatable and open to interpretation, not a statement of the obvious. The thesis statement is a clear, declarative sentence that often works best when it comes at the end of the introduction.

- Organization: Like any essay, the critical essay should have a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. As you support your point in the body of the essay, you should “divide up the proof,” which means structuring the body around clear primary supports (developed in single paragraphs for short papers or multiple paragraphs for longer papers).

- Support: (a) The primary source for support in the critical essay is from the text (or sources). The text is the authority, so using quotations is required. ( b) The continuous movement of logic in a critical essay is “assert then support; assert then support.” No assertion (general statement that needs proving) should be left without specific support (often from the text(s)). (c) You need enough support to be convincing. In general, that means for each assertion you need at least three supports. This threshold can vary, but invariably one support is not enough.

- A critical essay will always “document” its sources, distinguishing the use of outside information used inside your text and clarifying where that information came from (following the rules of MLA documentation style or whatever documentation style is required).

- Whenever the author moves from one main point (primary support) to the next, the author needs to clearly signal to the reader that this movement is happening. This transition sentence works best when it links back to the thesis as it states the topic of that paragraph or section.

- A critical essay is put into an academic essay format such as the MLA or APA document format.

- Grammatical correctness: Your essay should have few if any grammatical problems. You’ll want to edit your final draft carefully before turning it in.

Conclusion

As we leave this discussion, I want to return to what I said was the secret for your success in writing college essays: Your success with academic writing depends upon how well you understand what you are doing as you write and then how you approach the writing task. Hopefully, you now have a better idea about the nature of the academic writing task and the expectations behind it. Knowing what you need to do won’t guarantee you an “A” on your paper—that will take a lot of thinking, hard work, and practice—but having the right orientation toward your college writing assignments is a first and important step in your eventual success.

Discussion

- How did what you wrote in high school compare to what you have/will do in your academic writing in college?

- Think of two different writing situations you have found yourself in. What did you need to do the same in those two situations to place your writing appropriately? What did you need to do differently?

- Think of a writing assignment that you will need to complete this semester. Who’s your audience? What’s the occasion or context? What’s your message? What’s your purpose? What documents/genres are used? How does all that compare to the writing you are doing in this class?

Works Cited

Carroll, Lee Ann. Rehearsing New Roles: How College Students Develop as Writers. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2002. Print.

Thaiss, Chris and Terry Zawacki. Engaged Writers & Dynamic Disciplines: Research on the Academic Writing Life. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook, 2006. Print.

About the Author

L. Lennie Irvin teaches first year writing at San Antonio College, and has been a community college writing teacher since 1989. He is the CoDirector of the San Antonio Writing Project, and a PhD Candidate in Technical Communication and Rhetoric at Texas Tech University (projected to finish 2010).

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons AttributionNoncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License and is subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces. org/terms-of-use.